The emergence of companies that rely on branding and innovation rather than physical assets and employee base to generate financial returns has created new challenges for tax systems that were originally designed to tax assets based on their legal ownership and physical location.

Moreover, the physical barriers that often prevent multinationals from centralising tangible assets or an employee base in a jurisdiction do not inhibit the transfer of intangible assets in the same way, with multinationals able to divorce legal ownership and funding of intangibles from the activities that create or maintain the assets.

The commercial and legal drivers to consolidate ownership of a group's intangible assets, and the tax advantages from doing so in a low tax environment, have resulted in the prevalence of structures designed to centralise the global or regional ownership of intangibles. While these structures are most common in technology, software and pharmaceuticals, they also often occur in other industry sectors, including consumer goods.

A central focus of the BEPS Action Plan has, therefore, been to identify and address the impact of these structures. The tax landscape for any group with intangible assets has changed as a result, and this chapter discusses the key implications of these changes.

What are intangible assets?

Intangible assets, by their very definition, are not physical in nature. Often, intangible assets comprise know-how that cannot be legally protected, but that nonetheless provides a sustainable competitive advantage. However, in some cases, intangible assets may be represented by legally registered and protected intellectual property (IP).

The definition of intangibles for transfer pricing purposes is a vexed question, and has been the subject of much discussion as the BEPS Action Plan has evolved. The final report on Actions 8 to 10 settles on the following definition, which is incorporated into Chapter VI of the revised OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines:

"….something which is not a physical asset or a financial asset, which is capable of being owned or controlled for use in commercial activities, and whose use or transfer would be compensated had it occurred in a transaction between independent parties."

The OECD notes that a definition that is either too narrow or too broad can be problematic, and has deliberately chosen a definition that does not rely on a typical accounting or legal interpretation. The OECD's intent in presenting its definition is to provide clarity to taxpayers and tax authorities, and it goes on in the report to give examples of the types of intangible that fall within this definition, including both intellectual property, such as patents and trademarks that can be registered, and other assets such as know-how, trade secrets and contractual rights.

It also notes that some factors that contribute to the income earned by a group are, nonetheless, not themselves intangibles. Group synergies and local market characteristics, for example, are to be treated as comparability factors in a transfer pricing analysis, not intangible assets.

The definition of intangibles contained in the revised transfer pricing guidelines is also referenced in the template for transfer pricing documentation contained in the Action 13 final report. These require that the transfer pricing master file transfer should present, among other things:

A description of the group's overall strategy for development, ownership and exploitation of intangibles, including the location of principal R&D facilities and R&D management;

A list of the group's intangibles, which are important for transfer pricing purposes, and details of which entities legally own them;

A list of agreements including cost contribution arrangements, service agreements and license agreements;

A general description of the group's transfer pricing policies; and

Details of any transfers of interest in intangibles undertaken.

With this requirement for taxpayers to identify and document their intangible assets more explicitly, it is clear that there will be much more visibility in future for tax authorities on the intangible assets driving business value and taxable profit.

Key features of centralised IP ownership

Up to now, because legally protected IP has typically been easier to identify, value and transfer, it has often been the focus of multinational groups' tax planning structures for intangibles.

While it is true that there is no 'one size fits all' IP ownership structure, it is often the case that tax-advantaged IP structures, to the extent that local country controlled foreign company (CFC) regulations did not prevent such structuring, have had the following features:

Centralised legal ownership and funding of intellectual property assets (patents, trademarks and copyrights) in a single legal entity – the IP owner;

Limited functional activity in the IP owner itself relating to the control or execution of IP development and management of resulting risk, whether by employees or the board of directors;

Outsourcing of activity relating to the control and execution of development, enhancement, maintenance and protection of the IP; and/or

Outsourcing of commercial exploitation activity to, for example, a local distributor typically in a higher-tax jurisdiction.

Example of low-function IP owner

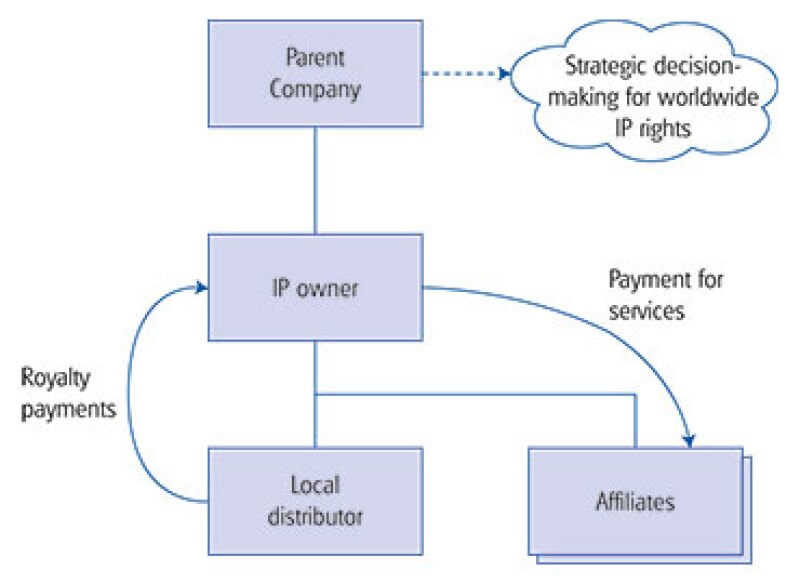

The existence and tax implications of this divergence between legal ownership and funding of IP assets from the functional activities relating to the development of the IP, seen in the typical low-functionality model described in Diagram 1, have been OECD's key focuses in Actions 8 to 10 of the BEPS Action Plan. The revised transfer pricing guidelines set out in the final report seek to confirm that profits are allocated to the economic activities that create value using transfer pricing principles, with a focus on decision-making and control functions.

Diagram 1: Example of low-function IP owner

IP owner and parent company relationship

IP owner has an exclusive right over the international IP rights rights outside of parent company's jurisdiction).

The entrepreneurial profit associated with the international IP rights accrues to the IP owner.

While there is some substance in the IP owner, strategic decision making with regards to the worldwide rights remains in the parent company.

The parent company does not seek to tax the income which accrues to the IP owner.

IP owner and local distributor

IP owner licenses IP to a local distributor who makes sales to third parties in the local jurisdiction.

IP owner and affiliates

IP owner enters into agreements with affiliates to provide R&D and other services applicable to the IP.

Why is tax a consideration when determining where to locate IP?

There can be many reasons why groups may choose to centralise their IP in a single location or company. Inevitably, tax often forms one of these considerations, with groups usually seeking to hold their IP in jurisdictions with:

Low headline corporate tax rates;

Tax deductions for amortisation of acquired IP;

Reduced tax rates for certain types of innovative income (that is, a preferential IP regime); and/or

Low or no withholding tax on royalties

Governments have recognised this trend, and have increasingly sought to modify their tax regimes to incentivise the retention and acquisition of valuable intangible assets.

This competition between jurisdictions has resulted in preferential IP regimes that enable groups to access low tax rates for IP income without locating significant amounts of IP development activity in the IP-owning entity. This level of competition has been deemed harmful by the OECD, which has made recommendations aiming to ensure that tax benefits are commensurate with the level of development activity performed by that entity.

These recommendations, which are contained within the final Action 5 report, clearly interact with the BEPS Actions that consider how transfer pricing principles should be applied to align profits with value creation. However, they seek to counteract separation of activity from IP ownership in a different way. Actions 8 to 10 focus on allocating IP profit to decision-making and control, while Action 5 focuses more strictly on aligning IP profit with the development activity itself. As discussed in the remainder of this chapter, the Action 5 and Action 8 to 10 changes all encourage groups to combine IP ownership, decision-making and control and development activity in the same legal entity.

The impact of BEPS on structures that separate IP ownership from decision-making and control

One long-standing criticism of the arm's-length principle is that, in application, it may be used to place too much emphasis on the contractual allocation of business functions and risks, rather than on the activities responsible for value creation. This focus on legal contracts can result in transfer pricing outcomes where profits are allocated to low-function entities that do not have significant involvement in creating those profits.

While the newly revised guidance explicitly confirms that the contractual arrangements remain the starting point for a transfer pricing analysis, it places a clear emphasis on the commercial substance of transactions and the actual conduct and contributions of the parties involved.

Legal ownership and contractual allocation of risk achieves no more than a risk-free return

The revised transfer pricing guidelines set out in BEPS Actions 8 to 10 require the actual intra-group transaction to be accurately delineated and analysed to determine whether the respective functions and conduct of the entities are aligned with the contractual relationship. Where the conduct of the entities does not support the contractual relationship, the actual conduct of the entities takes priority over the legal contractual relationship, and the profits from the arrangements are allocated to the entity that makes the key contributions to the creation of these profits.

A functional analysis is used to understand the economically significant activities and responsibilities undertaken, assets used or contributed and risks assumed by the parties to a transaction in order to determine arm's-length pricing. With respect to intangibles, particular attention should therefore be devoted to analysing the decision-making and control functions associated with the development, enhancement, maintenance protection and exploitation of intangibles that drive value creation in a business.

Crucially, the revised guidelines make it clear that entities that have only legal ownership of assets, or a contractual allocation of risk, should only receive a risk-free return under the arm's-length principle, with supply chain profit allocated instead to those entities undertaking economically significant activities.

One-sided versus multi-sided functional analysis

In determining arm's-length pricing, the revised guidelines emphasise the importance of understanding how value is created by the group as a whole, and the respective contribution of the parties to the transaction of that value creation.

A simple 'one-sided' functional analysis is unlikely to be sufficient to explain an entity's contribution to value creation in all but the simplest of cases, particularly in the context of the enhanced transparency over a group's entire value chain mandated by Action 13. Taxpayers will need to provide a more thorough analysis of functions, assets and risks, including consideration of the contributions of the transaction counterparties and the commercial context within which they operate.

It is not necessarily the case that this more rigorous analysis will inevitably lead to the increased use of profit split as a transfer pricing method; in situations where the contribution of one party to the intra-group transaction can clearly be demonstrated to be routine, the use of a traditional transfer pricing method or the transactional net margin method will remain appropriate. What is true, however, is that it is likely to require more effort by the taxpayer to demonstrate convincingly that this is the case in a multi-sided transfer pricing analysis.

Hard-to-value intangibles (HTVIs)

Another focus of the new guidelines is to include specific guidance on HTVIs, to protect tax administrations from the negative effects of information asymmetry between themselves and taxpayers.

Examples of HTVIs are those that are only partly developed, or not yet commercially exploited, at the time of the transfer; intangibles where financial projections are highly uncertain and intangibles where reliable comparisons are not available.

The revised guidelines enable tax administrations to use ex post evidence on financial outcomes of an intangible transaction (ie. information gathered in hindsight) as presumptive evidence of the appropriateness of the pricing arrangements.

The use of ex post evidence will be subject to safe harbours in certain situations. This includes cases where the taxpayer can provide reliable evidence that any variance between projections and the actual outcomes is due to unforeseen developments or foreseeable outcomes whose probability was originally estimated. Nevertheless, the ability of tax authorities to use hindsight to challenge taxpayers' pricing assertions results in an additional layer of uncertainty and documentation requirements for taxpayers.

What this means for IP structures

The potential implications of the BEPS Action Plan for structures that allocate significant value to a low-function IP owner are obvious and stark. To address the increasing risk of tax controversy, adjustments and penalties, taxpayers should either reset transfer pricing policies to allocate profits to (higher tax) territories in which the economically significant activities take place, or redesign their operating models to align economically significant decision-making and control functions with IP ownership.

The impact of BEPS on structures that separate IP ownership from performance of R&D activities

The changes to transfer pricing guidelines do not impact the legitimacy of the outsourcing of functions such as R&D to related parties, provided that these functions are properly controlled by the IP owner and rewarded on an arm's length basis. However, proposed substance requirements in preferential IP regimes may adversely impact arrangements whereby IP is beneficially owned by a different entity from the one that performs the R&D activity.

What is a preferential IP regime?

Many territories seek to incentivise the retention and commercialisation of IP in-territory, as well as the local performance of R&D activities.

They do this through both 'front-end' regimes, which focus on providing tax relief for expenditure incurred, and 'back-end' regimes, which apply to the income earned from the exploitation of the developed IP and are often referred to as patent or innovation boxes.

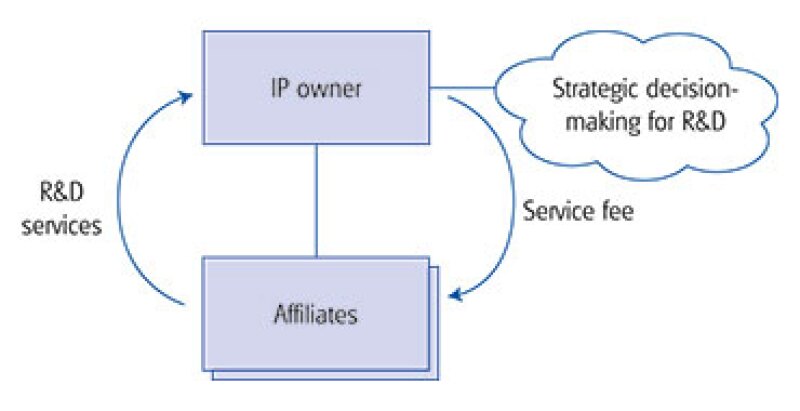

In the example shown in Diagram 2, a back-end IP regime may have historically been available to the IP owner in the territory where the entity is resident, regardless of the fact that it did not perform the underlying development activity which resulted in the creation of the IP rights. In addition, a front-end IP regime may also be available to the affiliates in the territory where they are resident.

Diagram 2: Separation of IP ownership from R&D

Overview of the OECD recommendations: the modified nexus approach

The OECD's final report on Action 5 defines parameters within which preferential IP regimes must operate so as not to be regarded as harmful tax competition. These parameters cover the types of IP which can be included within a regime and the method that must be applied to demonstrate that benefits are proportionate to substance.

Qualifying IP

Territories have historically taken different approaches to defining the scope of IP that can qualify for a preferential IP regime.

Action 5 requires a limitation of this definition to patents (under a broad definition) and copyrighted software that is the result of qualifying R&D.

Regimes that accommodate other IP, such as trademarks and trade names, will be required to amend their rules in line with the recommendations.

Substantiality requirement

The modified nexus approach seeks to create a direct nexus between the income eligible for benefits in a back-end preferential IP regime and the underlying activity that is performed on the creation of the IP.

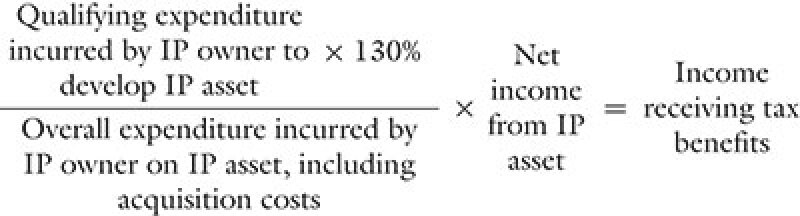

Rather than applying the transfer pricing principles stated in Actions 8 to 10, the modified nexus approach uses expenditure as a proxy for underlying activity, limiting the income qualifying under a regime to the proportion of qualifying expenditure incurred by the IP owner.

Jurisdictions will provide their own definitions of qualifying expenditure. However, these definitions will be limited to expenditure that is incurred for the purposes of actual R&D activities. This is also likely to include the types of expenditure that would qualify for R&D tax credits under the laws of different jurisdictions, but not expenditure such as interest, building costs or costs not directly linked to a specific IP asset.

Where parties other than the IP owners have performed underlying development, a restriction of benefits is likely to occur. This includes situations where affiliates have performed the underlying development activity but that activity has been under the control of, and funded by, the IP owner, as well as situations where the IP has been developed by another party (whether related or not) and then sold or licensed to the IP owner. Outsourcing of R&D to unrelated parties is not penalised, since this is treated as qualifying expenditure.

What does this mean for structures that separate R&D activity from IP ownership?

Below, the impact of the nexus approach in five different scenarios is considered. In each, R&D activities are separated in some way from either the entity, or the territory, that owns the IP.

1. R&D outsourced to a foreign affiliate

Expenditure incurred by the IP owner on outsourcing of R&D to overseas related parties would not meet the definition of qualifying expenditure. This will be the case even if the activity is strategically managed by the IP owner.

However, the expenditure incurred on the related party outsourcing would fall within the definition of overall expenditure. Therefore, the related party outsourcing would adversely impact the nexus fraction shown in the calculation above and, consequently, the amount of income eligible for benefits.

2. R&D carried out by an IP owner in another territory

The OECD report does not include any requirements on the location of the R&D activity that is carried out by the IP owner. That means, for example, that the R&D activities of an IP owner's foreign branches could give rise to qualifying expenditure. This is, of course, subject to the manner in which the recommendations are implemented into local tax law.

Where the IP owner has personnel carrying out R&D in foreign locations, the existence of a taxable permanent establishment and attribution of the IP owner's profit to that PE would need to be considered.

3. In-country R&D

The separation of R&D activity and IP ownership between legal entities within the same territory would not appear to be contrary to the objectives that the BEPS project is seeking to achieve.

However, there has been concern within the EU that treating outsourcing of activity to related parties in the same territory differently from outsourcing of activity to related parties in another territory might be contrary to EU freedoms in some cases. Therefore, it is expected that EU IP owners will be equally penalised for subcontracting development activity to affiliates within the same territory as they would if they had subcontracted the development activity to a foreign affiliate.

As with scenario one, the related party outsourcing would adversely impact both the nexus fraction and the amount of income capable of receiving benefits. Therefore, this creates a potential incentive to combine R&D activity with IP ownership in a single legal entity.

4. IP developed by an affiliate and then sold to an IP owner

The Action 5 report sets out the basic principle that only expenditure incurred by the IP owner on qualifying development activity following acquisition of the IP would be capable of being qualifying expenditure.

Acquisition costs (including licensing fees and royalties) would, however, be included in overall expenditures. The Action 5 report explains that such costs act as a proxy for overall expenditures incurred prior to acquisition. This is despite the fact that such acquisition costs will likely include a return (sometimes significant) for the previous IP owner, over and above the costs of development it incurred.

Furthermore, in the context of related party acquisitions, these will be deemed to take place at the market value of the IP transferred, regardless of the consideration paid.

Therefore, in circumstances where the IP was substantially developed prior to being transferred to the IP owner, the nexus fraction is likely to restrict the income capable of receiving benefits.

5. Global R&D – cost sharing

Where several affiliates jointly contribute toward the development of IP and share in the rewards under a cost sharing arrangement, each of them will economically be an owner of the IP. In such cases, each entity's overall expenditure will be equal to the amount that that entity contributes toward R&D expenditure. Where there is a mismatch between this amount and the physical contribution of R&D activity by the entity, the difference will be treated as related party expenditure, with a corresponding reduction in benefits.

This means that a cost sharing participant who funds R&D but does not carry out any R&D activity of their own will have a much lower nexus fraction than a company that both funds and carries out R&D.

Tracking and tracing compliance

Taxpayers that want to benefit from a post-BEPS preferential IP regime will need to track their cumulative expenditures in order to be able to substantiate the nexus between expenditures and income, and to provide evidence of this link to tax administrations.

In principle, this requires taxpayers to trace expenditure to each IP asset (that is, each patent). However, where such tracing would be unrealistic or would require arbitrary judgments, countries may allow taxpayers to trace expenditure to a product or, in limited circumstances, to a product family.

Regardless, this is likely to create an additional compliance cost for businesses that goes beyond the tax function, but focuses on the manner in which R&D personnel record their time.

Grandfathering and safeguards

The final Action 5 report confirmed that no new entrants should be permitted into an existing, non-compliant, IP regime after June 30 2016. 'New entrants' in this context includes both taxpayers not previously benefiting from the regime and new IP assets owned by taxpayers already benefiting from the regime. A patent that is filed, but not yet granted, on June 30 2016, would not be treated as a new entrant.

However, for companies and IP already within a regime, jurisdictions are permitted to allow taxpayers to benefit from the existing regime until a specified abolition date, which may not be later than June 30 2021.

This means that companies should consider what steps they can take to gain access to the grandfathered regimes, which might include acceleration of patent filings. It should be noted that, to prevent a rush of multinationals transferring their IP into existing non-OECD compliant regimes before the June 30 2016 deadline, to avail themselves of the grandfathering period, an additional recommendation was made that grandfathering treatment should not be granted for IP that is acquired directly or indirectly from related parties after January 1 2016, unless such assets already qualified for another IP regime.

The additional transparency requirements will also apply to any new entrants into a preferential IP regime after February 6 2015. This will include spontaneous exchange of information on the identity of new entrants, regardless of whether a ruling is provided.

Conclusion

The combined effect of Actions 5 and 8 to 10 on IP structures is that multinational groups that wish to attribute substantial profits to an IP owner and obtain the benefits of a preferential IP taxation regime, will need to confirm that the IP owner carries out not only the funding of the IP development but also the decision-making and control over development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation of the IP, as well as a substantial proportion of the execution of the R&D activity.

Companies that do not to align decision-making and control with IP ownership will likely need to revisit their transfer pricing arrangements and can expect enhanced scrutiny from tax authorities where returns are considered not to be aligned with value creation.

Companies that do not align R&D activity with IP ownership will likely see the benefits available to them under preferential IP regimes reduced.

For all multinational groups, the changed tax environment creates the need to review their strategy for the creation, protection and exploitation of intangibles.

|

|

Sarah ChurtonEY Tel: +44 (0) 20 7951 4064 Sarah Churton is a London-based executive director with 17 years of experience in UK and international tax. She recently spent two years on EY's UK tax desk in New York, where she worked closely with her counterparts from across EY's global tax desk network serving US headquartered multinational corporations. Sarah is a member of EY's international tax practice, where she advises on IP-related UK tax issues arising from acquisitions and disposals, investments into the UK, supply chain restructuring and IP centralisation. She has a portfolio of clients, both UK and US headquartered, with a particular focus on the life sciences sector. Sarah has published articles in several tax journals and is a regular speaker at tax seminars and conferences. She is a chartered accountant and has a master's degree in mathematics from Oxford University. |

|

|

Ellis LambertEY Tel: +44 (0) 207 951 0632 Ellis Lambert is a partner in EY's transfer pricing practice based in London, with 17 years of experience, including two years working on EY's UK tax desk in New York. Ellis advises clients across a range of industry sectors on their strategy for intangible assets and on the design, documentation and defence of their transfer pricing structures. Ellis also leads the negotiation of advance pricing agreements (APAs) and MAP claims with tax authorities in the UK and overseas, as part of clients' strategies for transfer pricing risk management. |

|

|

Ian DennisEY Tel: +44 (0) 1189 281 278 Ian Dennis is a Reading-based senior manager with more than nine years of experience in UK and international tax. He is a chartered accountant and chartered tax adviser, and holds a master's degree in mathematics from Liverpool University. Ian is a member of EY's international tax practice, specialising in the technology, media and telecommunications industry. Despite his specialism, he has retained a broad portfolio of clients in several sectors, and has advised many of these clients on IP-related UK tax issues. |