The OECD's profit split method (PSM) requires a full understanding of how value is created in a transaction, and an appreciation for both sides of the deal. It can provide a valuable transfer pricing (TP) approach in relevant situations, when it is determined to be the most appropriate method. However, the method has historically been used sporadically in the energy and resources (E&R) sector, whereas the comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method is most commonly used in relation to index-priced commodity transactions. The cost-plus method (often as a variant of the transactional net margin method, or TNMM) is applied to many types of services transactions.

This article looks at the extent to which the PSM, as articulated most recently by the OECD in their June 2018 paper (Revised Guidance on the Application of the Transactional Profit Split Method) can be applied in relevant circumstances to intragroup transactions within E&R-focused companies. The article outlines how the new OECD profit split framework is intended to be applied from a technical perspective, and then considers how some industry participants have successfully applied it.

The OECD's profit split method

On June 21 2018, the OECD released revised guidance on the application of the transactional profit split method (PSM) to related-party transactions in response to Action 10 of the BEPS Action Plan.

Application of the PSM

In Section 2.118 of the guidance, it re-affirms that an "exhaustive analysis" does not need to be undertaken to determine that the profit split method is the most appropriate method. Instead, the selected method should take into account its "relative appropriateness and reliability" compared to other methods.

The guidance specifically outlines three hallmarks to determine when the PSM might be appropriate:

1) Whether a "unique and valuable contribution" is made by each involved party;

2) Whether there is a "high degree of integration"; or

3) Whether there is a "shared assumption of risk".

Interestingly, the guidance states that the existence of unique and valuable contributions is "perhaps the clearest indicator" that the PSM may be appropriate (section 2.126). The guidance notes that the PSM might be considered in instances when there are few comparables or no good comparables. The guidance makes it clear that the absence of comparables should not immediately result in the automatic adoption of the PSM.

However, it does go on to say that the absence of comparables is an indication that the method may be appropriate. This might be particularly important in an E&R context, as high-quality comparables can be hard to find.

Finally, the guidance notes that one disadvantage of applying the method is its complexity. However, this may not be much of a disadvantage in the E&R industry, in which intercompany pricing for many decades has been very complex, but it could potentially be an issue if a tax authority is proposing a different method.

Profit-splitting factors

At the outset, the guidance notes (section 2.146) that the overriding objective of applying the method should be "to approximate as closely as possible the split of profits that would have been realised had the parties been independent enterprises". The guidance goes on to discuss that the split is performed on an "economically valid basis", and in many instances, refers to the importance of ascertaining the parties' "relative contributions".

The guidance adopts a broad approach to determining profit splitting factors, so long as they are appropriate and reliable, resulting in arm's-length outcomes for all relevant parties (section 2.172).

The guidance also makes specific reference to taxpayers' TP documentation master files and local files as a means of identifying drivers of business profit (section 2.173). This would suggest that if applying the PSM, groups should ensure their profit splitting factors align with the drivers of profit reported by the group in master and local files.

The guidance reinforces the notion that the approach to identifying profits to be split should align with the accurately delineated transactions as discussed in Chapter 1 of the OECD's TP guidelines. In other words, profits used should be those relating to the controlled transaction under review. In situations where a profit split is the most appropriate method, the guidance favours the split of actual profits when a party shares the same (or closely related) economically significant risks.

Conversely, in profit split situations where there are unique contributions, but a party does not assume economically significant risks, the OECD notes that the use of forecasted profits may be more appropriate (example 13 of the guidance exemplifies this approach). This is based on the assumption that the party assuming the economically significant risks manages and controls the risks in such a way that it is responsible for delivering the anticipated profits.

Finally, the 2018 guidance concludes with 16 examples covering a wide range of potential applications of the method. None of the examples are directly drawn from the E&R industry, although this does not mean that they cannot be applied by analogy.

The closest example is perhaps the one that focuses on the tea growing industry, which suggests that the tea grower and a related-party marketing entity could apply the PSM appropriately. If the tea grower is viewed as akin to a resource-producing company (an assumption that could apply in certain circumstances), then this could indicate the appropriateness of the method for transactions between resource-producing companies and their marketing counterparts.

PSM in the E&R sector

The energy and resources sector is diverse, with many different types of intercompany transactions covering many different types of products and services. This section draws out some of the situations where the PSM may be appropriate in the E&R sector, and discusses the potential means of determining the allocation of profits to be split.

Commodity trading

Within the E&R industry, commodity trading has been the sector in which historically the PSM has been most commonly applied. Different entities, or sometimes different permanent establishments of the same legal entity, will often jointly trade commodities on the same book (or in some other integrated manner).

Depending on the facts, the PSM is often viewed as the most appropriate method, as all three of the OECD's key gateway tests are often met:

1) The entities jointly managing a global trading book will normally be very closely integrated;

2) They will clearly share and manage key risks; and

3) Often they each make unique and valuable contributions.

The PSM is often applied by means of an appropriate allocation key. The relative remuneration of key value-adding traders or other employees is perhaps the most commonly used metric. As this is broadly a cost-based allocation metric, it often raises interesting questions about how to link bonuses to salaries, and who should be deemed to be a significant value-creating employee whose salary is included in the selected cost base.

Other metrics may include a simple weighted headcount or relative book value, amongst others. In certain circumstances, it may also be appropriate first to apply an allocation to capital before the allocation of residual profits, or alternatively, a reward to capital may be worked into the allocation mechanism.

Upstream/downstream

Another sector in which the PSM can be the most appropriate method is in transactions across the boundary between upstream and downstream (or midstream trading if present) parts of an extractives multinational.

For example, an entity may have extracted oil or gas before selling to a related-party marketing entity. The reward it pays to the related-party marketing entity may be structured as a form of commission or other fee. However, the PSM might be used as a corroborative or even primary method to establish the commission fee.

The application of the method in such a situation is complex, but can have a compelling outcome when performed appropriately and with the right fact patterns. Companies applying this method appropriately closely analyse the relative value of the functions, risks and assets (FAR) contributed by both the extractive entity and the marketing entity.

As noted above, the guidance often seeks to analyse the "relative contribution" made by each party in applying the PSM. This is often done by independently valuing each FAR contribution made by a party.

The approach often used by companies in applying the arm's-length principle requires determining a mechanism for comparing assets to risks to functions on a like-for-like basis, an inherently difficult exercise. For example, how do you compare the value added by a team of reservoir engineers with the value added by an extractive asset?

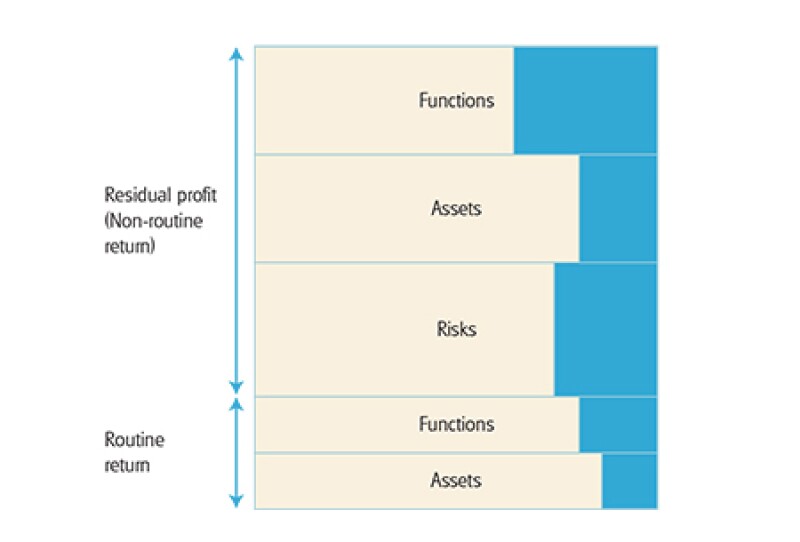

The resulting profit is then split in proportion to the relative value of each contribution, often after first rewarding more routine functional and asset contributions (Figure 1, the light yellow bars represent the relative contribution of the production entity while the blue bars represent the relative contribution of the marketing entity).

Figure 1: Representation of upstream/downstream profit split

Services in a cost sharing context

The E&R industry has always represented an intrinsic coming together of entrepreneurial drive and natural endowments. When the facts and circumstances are appropriate, value-adding services, or sometimes the intellectual property associated with them or generated by them, are increasingly being priced by groups with reference to the PSM, and the relative contribution of those services in comparison to the value contributed by the underlying asset.

Key to determining the profits attributable to services or the intellectual property (IP) in question is determining how to split profits between two of the fundamental drivers of value touched on above: (1) the asset, such as molecules of oil or gas under the ground (which are valuable but difficult to access), and (2) the people that extract the molecules in question and take them to market.

The PSM is increasingly seen as a potential solution to this issue. Once again, the application of the split when applied by companies often focuses on the relative contribution of the key FAR provided by the service or IP-owning entity, and the relevant asset-owning entity.

Such splits are often difficult to perform due to the long time frames present in the industry. For example, IP used in drilling may lead to cash flows from the sale of oil many years afterwards. Applied in the right circumstances, the PSM can be considered an important mechanism for demonstrating arm's-length TP outcomes.

Other sectors

Other sectors in which the PSM might be correctly applied include determining the reward for intangibles in the oil-field services industry, the pricing for strategic oversight services to either a wind or solar asset-owning company, or the pricing of technology in a refining context.

PSM considerations

The guidance detailing the appropriate manner to apply the PSM in an arm's-length manner has been updated by the OECD over the last few years, and the guidance is likely to continue to be updated. It is an area industry practitioners should continue to monitor.

The PSM is a complex method to apply, but in many ways, this can be a complex industry. When applied correctly and when the facts and circumstances are appropriate, the PSM's importance as a means of demonstrating adherence to the arm's-length standard for E&R transactions is likely to become even more relevant.

© 2019. For information, contact Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited.This communication contains general information only, and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, its member firms or their related entities (collectively, the "Deloitte network") is, by means of this communication, rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your finances or your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser. No entity in the Deloitte network shall be responsible for any loss whatsoever sustained by any person who relies on this communication.

Mark Barker |

|

|---|---|

|

Associate director Deloitte UK Tel: +44 20 7007 0114 Mark Barker is an associate director in Deloitte UK's London office. He has eight years of experience in transfer pricing controversy, advance pricing agreements and risk identification, having previously worked in the Australian Taxation Office's economist practice before joining Deloitte's London TP team a year ago. Mark has specialist skills in the energy and resources sector, including experience in iron ore, coal, LNG, petroleum and LME-based metals. In addition, Mark has experience pricing financing arrangements for upstream E&R production assets, and specialises in royalty pricing and intangible asset valuation projects outside the E&R sector. Mark has a Bachelor of Commerce with majors in economics and finance. |

Aengus Barry |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Deloitte UK Tel: +44 20 7007 4331 Aengus joined Deloitte UK's transfer pricing team 16 years ago and since that time has spent a significant portion of his career assisting clients in the energy and resources industry. He has particular experience in complex energy and resources pricing projects, from using risk pricing statistical techniques to support the marketing margins retained by mining groups to one of our most difficult diversionary LNG cargo pricing assignments. Aengus has experience delivering a broad range of TP services, from documentation and compliance reports to IP planning exercises and debt pricing projects. He has worked on a number of APAs and also has experience of wider international tax issues through participation in several tax structuring projects. Aengus holds both bachelors and masters degrees in economics. He is a CFA charter holder and was awarded the ATT qualification. |