India is the world's third largest customer of oil and petroleum products after the US and China. India's rapid industrialisation, along with a rise in population and high economic growth, has ensured an increase in energy demand. According to a recent Make in India report, about 48% of India's sedimentary area is yet to be explored, which offers significant opportunities in the industry. The exploration of oil and gas (O&G) reserves requires significant investment, specialised technology and government approvals, among others. Over the last two decades, the India's government has introduced several policy reforms to remove obstacles and provide an equal playing field to both private and public players in the upstream O&G sector in India.

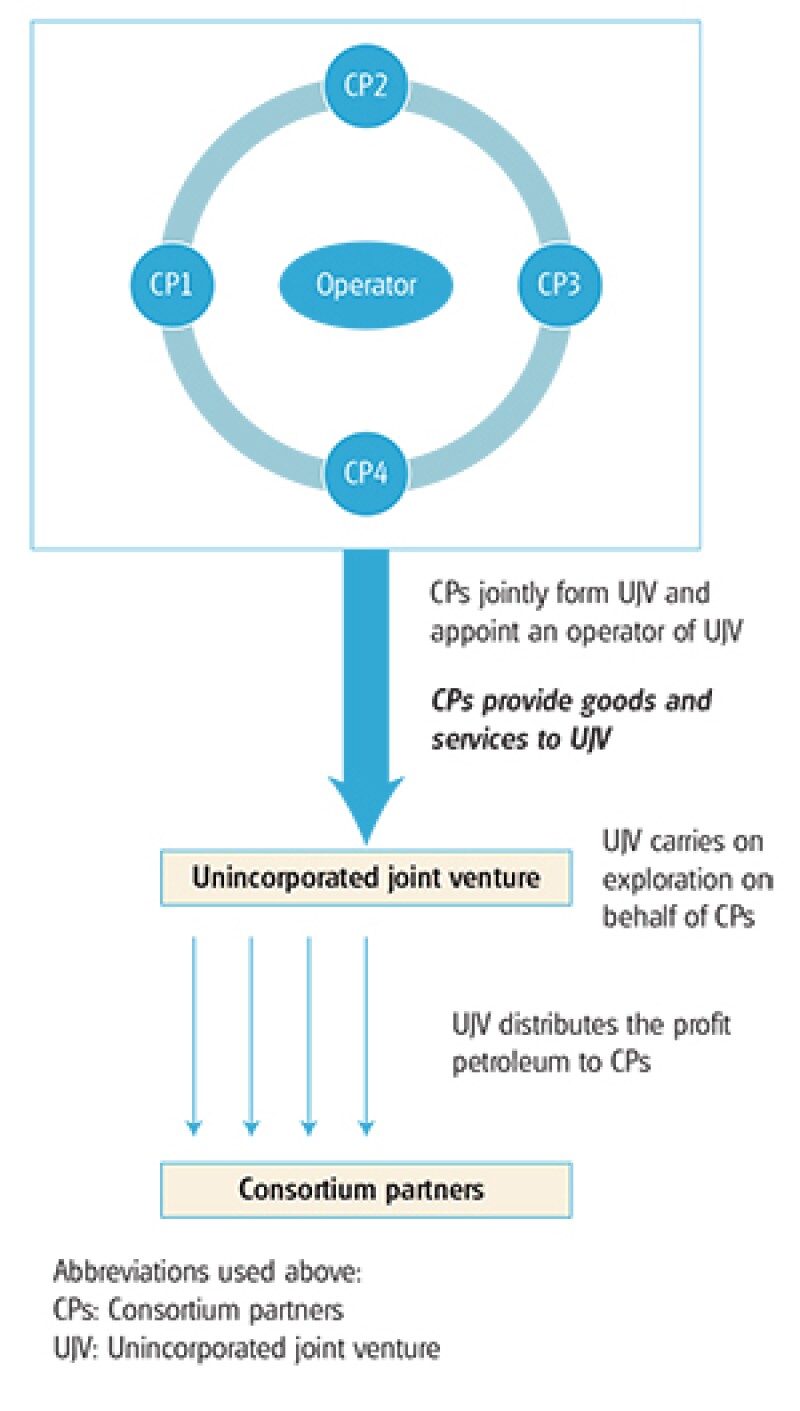

Figure 1: A typical consortium/joint venture model used in the upstream O&G sector |

|

Consortium/joint ventures in O&G sector

Companies (related or unrelated) in the O&G sector typically join together to carry out exploration and exploitation of O&G reserves. To do this, they enter into production sharing contracts (PSCs) with the government or public-sector companies nominated by the government. These companies usually form consortiums for mutual benefits, which are usually organised as unincorporated joint ventures (UJVs) (see Figure 1).

A UJV typically works as a pass-through entity (with no legal existence of its own) and operates through a joint bank account from which all the exploration, development and production costs are paid. This industry practice aims to avoid any conflicts that may arise between different O&G players if they were to work on an isolated basis.

The companies/consortium partners (CPs) designate an operator of the UJV, which takes control of the day-to-day operational requirements of the JV. Oil and gas operations are often conducted through UJVs for several reasons, including the large investments involved, the benefits of pooling of resources, the mitigation of risks, and alignment with governmental interests by involving a government company as a consortium partner.

Cost-to-cost provision of services

Most JV consortium partners possess significant technical knowledge and experience, which they can provide to the UJV in the form of professional, engineering, technical, administrative or other services related to the UJV's operations. The services are provided to the UJV on a cost only basis by the CPs themselves, or through their group companies. In other words, not adding a profit mark-up on the cost incurred in the provisioning of services. Typically, two types of costs are charged to the UJV:

1) Direct costs: these are charged by the operator or consortium partners/unrelated parties for goods (equipment, machinery, etc.) and services provided to the UJV; and

2) Indirect costs: these are incurred by the operator/consortium partners for the management, strategy planning and administrative assistance to the UJV. These costs are not charged directly, but based on cost allocation mechanisms.

Out of the total oil produced, a specific portion is used to recover the costs incurred by the operator. That portion is called 'cost petroleum.' The balance of the oil produced is split among the CPs and is known as 'profit petroleum.' Profit petroleum is the main source of revenue for non-operators, thus there is a mutual interest to limit the amount of cost petroleum.

The operations of an exploration and exploitation entity are quite complex, entailing large-scale operations and requiring technical expertise. Charging a mark-up on costs by each partner providing services leads to commercial difficulties. By adopting a cost only policy, CPs aim for administrative simplicity, avoiding conflicts of interest, achieving overall transparency and limiting the amount of cost petroleum.

Therefore, companies providing services to the UJVs charge only cost (without any mark-up). Companies in such arrangements generally provide services at cost due to group policies, which also entitles them to receive services at cost only in similar circumstances. This is an often-followed industry practice, which is prevalent in most upstream operations worldwide.

Government contracts

The government's role in these arrangements is important. The recoveries by consortium partners for provisioning of services to UJVs are governed by PSCs. Since the government of India or a public-sector entity is normally entitled to a share in the profit petroleum under a PSC for exploration in India, CPs typically are not permitted to earn profits from the services provided to the UJVs.

Until recently, the Model PSC (in section 3.1.4) issued by the government of India under the new exploration license policy (NELP) recognised that the charges should be made on a cost-to-cost basis. This confirmed the industry practice of a cost-to-cost charging mechanism in the upstream O&G industry.

However, India's government replaced the NELP in March 2016 with the hydrocarbon and exploration licensing policy (HELP). Under HELP, the government is not concerned with the costs incurred in a project, because it receives a share of the gross revenue from the sale of O&G. HELP focuses on a revenue-sharing model rather than a profit-sharing model.

Transfer pricing challenges

The receipt of cost-to-cost services may not create any TP challenges in the jurisdiction of the service recipient. However, it may create numerous TP challenges in the service provider's jurisdiction, especially when the service providers do not have any interest in the upstream asset, but provide services due to the participation interest of a group affiliate or under a cost contribution arrangement (CCA). For the sake of brevity, the implications for services provided under a CCA are not discussed in detail below.

In India, service providers providing cost-to-cost services are not unaffected by TP litigation. The definition of intragroup services under the OECD's 2017 TP guidelines alludes to the test of whether activity provides a group member with economic or commercial value to enhance or maintain its business position.

If the answer is yes, then there should be an arm's-length charge for that service (the amount that would have been charged to an independent enterprise). The 2017 TP guidelines also state that an independent service provider would charge for its services, rather than just provide services at cost.

Commercial transactions between independent enterprises are rarely on a cost-to-cost basis. Therefore, tax authorities argue that cost-to-cost pricing is not arm's-length pricing, and hence propose TP adjustments for the service providers. To aggravate the issue further, if a TP adjustment is sustained, India's secondary adjustments provisions are triggered, inflicting further pain on the taxpayer.

In addition to the risk of a TP adjustment and a secondary adjustment, there could also be penal implications if the tax authorities allege that the service provider did not charge a mark-up to shift profits and evade taxes intentionally.

Transfer pricing strategy

Leaving industry practices aside, it is difficult to contend that the cost-to-cost provision of services adheres to the arm's-length standard. However, industry practices cannot be conveniently ignored. There are also scenarios where cost-to-cost services are provided to independent enterprises in the upstream O&G industry. Such examples can provide a logical comparison to test the arm's-length nature of similar transactions with affiliates. In those cases, the comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method can be applied.

In an aggressive TP audit landscape such as India, some service providers apply a profit mark-up to avoid any adverse inference by the tax authorities. Usually, the service providers assume a limited risk, and the return is not contingent on the outcome of exploration. Therefore, a nominal mark-up can be applied to determine the arm's-length pricing.

Any benefit that accrues directly or indirectly to the service provider for being part of a group with a cost-to-cost policy (for example, any cost-to-cost services received from the affiliates) will also be considered while conducting a TP analysis. Such a benefit may provide economic reasons to compensate for the loss of revenue to the service provider working on a cost-to-cost basis. This may lead to the discussion of intentional set-offs, which should be individually analysed (as per OECD guidelines). Also, it is completely up to the tax authorities to allow or disallow such set-offs.

India's litigation landscape

The practice of providing services on a cost-to-cost basis is typically rejected by Indian tax authorities, as they do not agree with the cost-to-cost charging mechanism used by Indian service providers. The tax authorities disregard the industry practice and contend that the arm's-length standard requires a mark-up to be charged for services provided.

The most prominent approach used by tax authorities to determine the arm's-length price for such transactions is to determine the net margin earned by similar service providers in the market. The net margin is then applied to the cost of services provided by the service provider, to arrive at the arm's-length price and consequently the TP adjustment.

This position taken by the tax authorities is usually challenged in appellate proceedings before the Commissioner (Appeals) or the Dispute Resolution Panel (DRP), and later at income tax appellate tribunals and courts.

The cost-to-cost value

The landscape around the cost-to-cost charging mechanism for services in the O&G sector is an industry practice consistently followed by O&G companies in India and globally.

There are practical reasons for this approach, including commercial reasons and sovereign restrictions. However, alternative approaches also need to be examined in detail. Since the introduction of HELP, the focus of PSCs is expected to shift from a profit-sharing model (NELP) to a revenue-sharing model (HELP).

The use of this mechanism would need to be examined on a case-by-case basis, and the business rationale for such use, given the litigation trend in India regarding such cost-to-cost arrangements.

The defence of a cost-to-cost service provider's TP is not an easy task, as an adjustment in the service provider's jurisdiction may lead to double taxation. However, an alternative dispute resolution mechanism in the form of the mutual agreement procedure (MAP) under the framework of income tax treaties, and advance pricing agreements (APAs) under the Income-tax Act 1961, may be considered to deal effectively with double taxation.

This article was written by Bhavik Timbadia and Ankit Goel of Deloitte India, with the contribution of Saurabh Singla.© 2019. For information, contact Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. This communication contains general information only, and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, its member firms or their related entities (collectively, the "Deloitte network") is, by means of this communication, rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your finances or your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser. No entity in the Deloitte network shall be responsible for any loss whatsoever sustained by any person who relies on this communication.

Bhavik Timbadia |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Deloitte India Tel: +91 124 679 3883; +91 981 933 4259 Bhavik Timbadia is a partner in Deloitte India's Delhi office. He has over 15 years of experience advising multinational companies on transfer pricing matters across various industries such as technology, financial services, consumer products, infrastructure, chemicals, steel, energy and automotive. Bhavik's experience ranges from preparing contemporaneous documentation, advising on planning opportunities, value chain analysis, negotiating advance pricing arrangements (APAs) and assistance in TP litigation up to the Supreme Court. He has assisted clients in dispute resolution through the negotiation of multiple APAs in India for transactions in complex manufacturing set-up, management support services, marketing intangibles, corporate guarantees, interest attribution to permanent establishment in India, investment advisory activities and back-office services. He is a regular speaker at various tax and industry forums and has authored various articles in tax journals and newspapers on TP issues. Bhavik is a qualified chartered accountant and holds a master's degree in commerce from the University of Mumbai. |

Ankit Goel |

|

|---|---|

|

Director Deloitte India Tel: +91 92124 01075 Ankit Goel is a director in the transfer pricing practice of Deloitte India based in Gurgaon. He is a member of Institute of Chartered Accountants of India. Since qualification in 2005, he has specialised in the transfer pricing field. Ankit has worked extensively in various TP assignments relating to planning, documentation and litigation for a number of renowned multinational companies. He has worked in the oil and gas industry with some of the largest multinational O&G corporations to assist them with their TP litigation, advance pricing agreements (APAs) and compliance and advisory assignments. Ankit is a prolific speaker and has presented on diverse technical TP issues at various internal and external forums. |