On December 10 2018, the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland ruled that inter-company royalty payments made by a Swiss subsidiary to its Dutch parent company had no commercial justification and resulted in a hidden distribution of profit. Ultimately, tax evasion occurred at the federal and cantonal/municipal levels, and the taxpayer was charged with a criminal offence and punished with a fine equal to two-thirds of the tax evaded (Decision 2C_11/2018).

As Switzerland promises to align with international tax policies, this is an early sign of the nation's growing appetite in tackling tax evasion.

Switzerland's tax policy post-BEPS

In a post-BEPS world, Switzerland's tax policy is pursuing two main directions. Firstly, it is seeking to maintain its attractiveness through two main measures:

1) The introduction of new tax measures through an internationally accepted patent box regime, research and development (R&D) super-deduction schemes, with considerable cuts to cantonal corporate income tax rats (CIT); and

2) Secondly, it is preparing to chase taxpayers shifting profit abroad.

Tax evasion

With regards to tax evasion, transactions that are increasingly on the Swiss tax authority's radar are those with more complex group structures involving intangibles and intellectual property (IP) risk allocation arrangements. This comes at a time when inter-company transactions involving intangibles are addressed as one of the key issues tackled by the BEPS project.

In July 2017, the OECD's transfer pricing (TP) guidelines were updated in line with the final BEPS report (addressing Action 8 to 10). According to the update, multinational enterprises (MNEs) should focus on development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation (DEMPE), with a view to determining who in the MNE undertakes, and more importantly, controls these functions and their related risks.

The goal is to equip governments with domestic and international instruments to ensure that profits will be taxed where economic activities generating these profits are performed and where value is created. Ultimately, this is to avoid both double taxation and non-taxation.

Switzerland and the DEMPE approach

The OECD's discussions on intangibles have been a great inspiration for many tax authorities around the world, including the Swiss, and this has allowed the consolidation of key concepts that form the premise of the arm's-length principle: the prevalence of the parties conduct over contractual arrangements and economic substance, with key features including decision makers and control over risk.

Under DEMPE, these key concepts preserve their importance. However, the DEMPE approach added a further level of examination. To retain returns derived from the exploitation of an intangible, one must distinguish between:

1) MNE group member(s) holding the legal ownership of the intangible;

2) MNE group member(s) taking control over the DEMPE functions, asset and risks (FAR); and

3) MNE group member(s) to whom the execution of the DEMPE functions are outsourced.

Ultimately, MNE members making contributions that are more significant should receive relatively greater compensation. The rules of the game have not changed, however, the scope of the analysis has now increased.

When an intercompany transaction is under review, a DEMPE analysis will be required to provide a holistic view of the contributions made by all the MNE group members involved (not only by those MNE group members transacting bilaterally). Taxpayers and tax authorities are increasingly leaning towards such a holistic analysis.

Other BEPS initiatives such as the master file, country-by-country reporting (CbCR), and an increased interest for advance pricing agreements (APAs), mutual agreement procedures (MAPs), and multilateral joint audits confirm this trend.

The Swiss Federal Supreme Court's 2018 decision (Decision 2C_11/2018) is anchored to the key concepts that form the basis of the arm's-length principle. However, the view of the authors is that neither the court, nor the taxpayer, have succeeded in embracing the holistic approach at the core of the DEMPE analysis.

December 2018 Supreme Court challenge

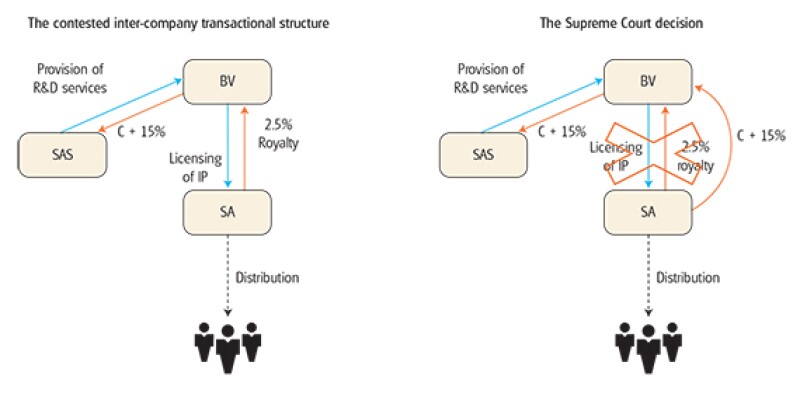

Decision 2C_11/2018 concerns a Swiss company (SA) that is a resident in the canton of Geneva, and is involved in the manufacturing and distribution of pharmaceutical and chemical products. Furthermore:

SA is part of multinational with a parent company (BV) in Holland;

SA is subject to a royalty payment equal to 2.5% of its turnover for using the results of R&D activities conducted by a French sister company (SAS);

The R&D activities were delegated by BV through a formal inter-company contract to SAS, while compensating SAS's activities with a cost (plus 15%);

The cantonal tax administration claimed a hidden distribution of profit leading to tax evasion at federal and cantonal/municipal tax levels. The claim concerned multiple fiscal years during the period 2003-2011;

The cantonal claim was made as the inter-company royalty payments were deemed to have no commercial justification;

The tax adjustment claimed amounted to the royalty payments made to BV during the years under review, minus the cost (plus 15% due to SAS); and

The criminal prosecution resulted in a penalty equal to 75% of the evaded taxes.

The commercial relationship

According to the inter-company agreement, SA is subject to a royalty payment to BV, granting access to the results of the R&D activities executed by SAS. The court concluded that the Dutch parent company is a shell company, and as a result, disregarded the contractual arrangement between SA and BV. It concluded that the conduct of the parties prevails over contractual arrangements.

The Supreme Court mentions the 1995 and 2010 versions of the OECD's TPG, and there is no reference to the new guidance on IP issues in the 2017 version. In the decision, the SA stated to the court that the BV assumes important financial, regulatory and operational risks, for which it should retain a return (paragraph 7).

It is very important to stress that the Federal Supreme Court can only correct facts if it finds that they have been established in a flagrant manner by a lower court, or that they have been based on a violation of the law. This was not the case here.

Judgment of the Supreme Court

For procedural reasons, the Supreme Court could not accept the additional facts brought to the table by the taxpayer. As a result, the court restated the conduct of the parties based on the facts made available by the lower court:

The Dutch parent company (BV) did not hold the required substance to entitle it to a royalty return. It was not involved in the group's R&D activity, it did not have any qualified personnel until 2007, and had an average number of three employees in 2010 and 2011. The BV was not even the legal owner because the patents were registered in SA's name;

SA was re-stated as the economic and legal owner of the R&D results. The SA had 60 employees and made the strategic decisions over the R&D functions. It gave instructions to the French company, which had an executive role; and

SA would have entered into an R&D agreement directly with SAS if all the related companies behaved according to the arm's-length principle. As a result, the payment to BV is not commercially justified.

Figure 1

Determining arm's-length pricing

The High Court of Geneva's decision (which was accepted by the Supreme Court) does not explicitly specify the TP method used.

However, it noted that since the Dutch parent company is a shell company, the fees which are not commercially justified correspond to the amount of fees (exceeding the costs) corresponding to SAS for carrying out the R&D activities. The pricing between SAS and BV is not questioned and is assumed to be at arm's length.

SA brings what seems to be an important new argument to the Federal Supreme Court: a comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method is potentially applicable. According to the plaintiff, the royalties in question were comparable to those paid to third parties by the group, and hence at arm's length. SA had not presented a CUP analysis to the lower courts, so for procedural reasons, the federal court had to reject the CUP method, and ruled against the Swiss taxpayer while ascertaining the existence of the hidden distribution of profit leading to tax evasion.

Key takeaways

The Supreme Court ruled that the transaction between BV and SA was not commercially justifiable, ultimately rejecting the existence of a transaction between BV and SA while establishing that SA should retain all the profit once the R&D services of SAS were compensated (with a cost plus and appropriate margin).

The TP method ruled by the courts establishes inter-company pricing as if SA had contracted directly with SAS for the provision of R&D activities. The method applied by BV (cost plus), as well as the level of mark-up (15%), used to price the transactions between SAS and BV were not reviewed by the courts.

Essentially, the inter-company pricing ruling between BV and SA depends on another inter-company pricing (between SAS and BV), whose arm's-length nature is not tested.

The Supreme Court did not include the inter-company transaction under review within a holistic approach. A complete DEMPE analysis would have required a review of the functions performed at the level of SAS in the context of the MNE's entire value chain. The court accepted the TP method applied by BV to the SAS without discussing who the employees of the SAS are and without specifying the functions, assets and risks of SAS (relative to the ones of SA and BV).

A holistic DEMPE analysis requires clearly identifying the profit drivers of the MNE's business, as well as the specific activities for each DEMPE function in order to ascertain their relative importance. The analysis of the contributions of each of the three MNE group members (SA, BV and SAS) to the DEMPE functions would indicate the proportional share of income to which each of them is entitled.

The conclusion of such an analysis could have led to a different outcome on the TP method, and hence on inter-company pricing. A potential conclusion could have been that SAS's contributions are such that SAS should receive a royalty on sales rather than a cost plus compensation.

The French might be inspired by this decision to compare the royalty initially paid to BV versus the cost plus received by SAS (that can be up to 244% higher than the cost plus 15% paid to SAS).

Avoiding the risk of double taxation

French tax authorities might scrutinise the TP between SAS and BV and conclude that SAS should have received a far higher compensation. The same CUP method presented by the taxpayer before the Supreme Court may even inspire the French tax authorities to question the compensation SAS received for performing R&D activities. If this occurred, double taxation would arise.

The double taxation risk could have been prevented by taking an alternative dispute resolution approach. The involved group companies could have initiated a multilateral MAP, engaging the tax authorities of the three countries.

Here, a DEMPE analysis could have ensured that the three MNE group companies involved would have been correctly compensated in line with their respective contributions to the entire value chain. By choosing such an approach, SA might have ended up with a smaller profit, and perhaps the same level of profit shown in its profit and loss statements. This way, the Swiss company and its board members could also have avoided criminal charges in Switzerland (or at least have reduced their criminal liabilities).

With the Supreme Court's decision, should the French tax administration claim a bigger piece of the tax pie, it is unlikely that the Swiss Federal Tax Administration (FTA) would agree to enter into a multilateral MAP.

In Switzerland's post-BEPS quest to chase taxpayers shifting profit outbound, and in the case of tax audits, focus should be given carefully to selecting the available dispute resolution mechanisms as early as possible in the cycle, as well as to pursue a complete DEMPE analysis and to comply with the procedural requirements. The ultimate intent should be to comprehensively and promptly solve the TP conundrum rather than moving the problem from country to country.

Caterina Colling Russo |

|

|---|---|

|

Senior advisor Tax Partner AG, Taxand Switzerland Lausanne Tel: +41 44 215 77 56 caterina.collingrusso@taxpartner.ch Caterina Colling Russo has more than 14 years full-time experience in transfer pricing (TP) consulting. Before joining Tax Partner in 2016, Caterina previously held specialist TP positions within global international tax and TP firms. She has worked in Amsterdam, London and Rome. She is a TP advisor for listed and non-listed Swiss and international multinationals. Caterina is a speaker at tax seminars, and has published various articles and books on TP. Tax Partner is one of the leading tax firms in Switzerland. With a team of 39 professionals, the firm advises on a range of multinational and national corporate clients, as well as individuals. In 2005, Tax Partner co-founded Taxand, the first global network with more than 400 tax partners and over 2,000 tax advisors from independent member firms in over 40 countries. |

Prof. Dr. René Matteotti |

|

|---|---|

|

Of counsel Tax Partner AG, Taxand Switzerland Zurich Tel: +41 44 215 77 61 René Matteotti is a tax attorney and tenured tax law professor at the University of Zurich. His areas of expertise include corporate and international tax law (including transfer pricing). He has long-standing practical experience as a tax attorney in representing domestic and international clients before tax authorities and courts. In particular, he supports enterprises in dispute resolution in tax audits, tax ruling requests and mutual agreement procedures. He also regularly provides opinions on complex tax law issues. Tax Partner is one of the leading tax firms in Switzerland. With a team of 39 professionals, the firm advises a range of multinational and national corporate clients as well as individuals. In 2005, Tax Partner co-founded Taxand, the first global network with more than 400 tax partners and over 2,000 tax advisors from independent member firms in over 40 countries. |