Last year saw progress on a global scale and with a speed unprecedented in the international tax policy arena.

Within the OECD's Centre for Tax Policy and Administration (CTPA) Achim Pross has overall responsibility for exchange of information, five of the 15 BEPS actions, as well as the Forum on Tax Administration and the OECD's work on serious non-compliance, including tax crimes and other financial crimes. |

We went from a world where information exchange upon request was the only universally agreed standard, to a fully developed automatic exchange standard with commitments to implement by more than 90 jurisdictions, including practically all financial centres around the world. And by December it had already been translated into an EU directive. This provides a step change in the ability of the international community to tackle offshore tax evasion. While all of this happened incredibly fast, of course it did not come out of nowhere.

The game changer in automatic exchange was the enactment of the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) in 2010 and the subsequent development of an intergovernmental approach to its implementation by the US in close cooperation with the G5 (Italy, France, Germany, Spain and the UK). This moved the design of FATCA implementation from a regime of automatic reporting by financial institutions directly to the Internal Revenue Service in the US, not dissimilar to the US Qualified Intermediaries regime - a US withholding tax relief system allowing financial institutions to claim relief from US withholding tax on behalf of customers by assuming so-called Qualified Intermediaries status - to the traditional model of automatic exchange where information reporting obligations are based on domestic law, information is reported to domestic authorities and is subsequently exchanged between governments.

In fact, article 6.3 of the first Model 1 intergovernmental agreement (IGA) to improve tax compliance and to implement FATCA, published in June 2012, already contained the seeds for a common standard as it committed the signatories to develop "a common model for automatic exchange of information, including the development of reporting and due diligence standards for financial institutions".

Shortly after that, banks and some of their associations started contacting us at the OECD. They accepted that financial institutions were going to have an expanded role in international tax compliance, but were concerned about the possible emergence of a multitude of different and potentially conflicting international reporting and withholding tax regimes which may have been impossible to operate and would have certainly led to manifold increases in compliance costs. The message was this: we are willing to work on a global reporting standard, but it needs to be one single global standard. At the same time civil society was making a strong and vocal case about a move to automatic exchange of information and the withholding tax agreement with Switzerland failed in the German Parliament.

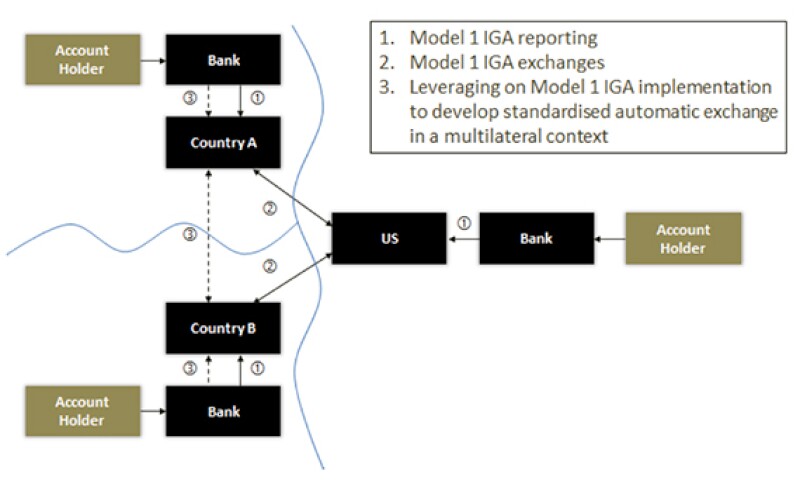

It was then the pilot initiative launched by the finance ministers of Italy, France, Germany, Spain and the UK - by accident the same countries that cooperated in the development of the IGA - that took the next logical step and committed their countries to exchange among themselves the type of information they were agreeing to exchange with the US under FATCA. There may have been an EU law angle to this development (Article 19 of the EU Administrative Co-operation Directive contains a most favoured nation clause under which member states are bound to provide any other EU member state that requests it with the same level of information as they provide to third countries), but the key was this: given the investment that governments and financial institutions were making to implement FATCA around the world it made sense to leverage off these investments and, using FATCA as a baseline, develop a global automatic exchange standard - which then became the "common reporting standard" or "CRS" (see Diagram 1).

Diagram 1: Development of global information exchange framework |

|

Following the launch of the pilot initiative, automatic exchange gained further political momentum. In July 2013 the G8 leaders under the UK G8 presidency endorsed the OECD report "A Step Change in Tax Transparency" (http://www.oecd.org/ctp/exchange-of-tax-information/taxtransparency_G8report.pdf) and in their communiqué committed to "establish the automatic exchange of information between tax authorities as the new global standard…"

With the G8's impetus, and earlier support within the G20 context, the G20 leaders, at their summit in St Petersburg in September 2013, expressed their full support for the OECD work, calling for the presentation of the standard in time for their February 2014 meeting and the finalisation of the technical work by summer 2014. In the meantime, the pilot initiative launched by the G5 was attracting more and more countries and by the summer of 2014 already more than 60jurisdictions had committed to early adoption of the CRS. To meet the ambitious G20 timetable, delegates from OECD and G20 countries, tasked with developing the standard, had to work sometimes around the clock to make this happen, not least my own team here at OECD. And finally this could not have been done without close consultations with business, often working to extremely demanding timelines.

So we ended the year with a standard approved by the OECD Council, endorsed by G20 leaders, with 93 jurisdictions committed to its implementation and an approved EU directive translating it into European law. Only five financial centres - Bahrain, the Cook Islands, Nauru, Panama and Vanuatu - have not yet committed to it and the clear hope is that they will also come on board (see Table 1). The standard is optional for non-financial centre developing countries and technical assistance to help them implement it is offered via the Global Forum on Transparency and the Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes.

Table 1: CRS - Status of commitments

JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2017 |

Anguilla, Argentina, Barbados, Belgium, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Bulgaria, Cayman Islands, Chile, Colombia, Croatia, Curaçao, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominica, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Finland, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Greenland, Guernsey, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Isle of Man, Italy, Jersey, Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mauritius, Mexico, Montserrat, Netherlands, Niue, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Seychelles, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands, UK, Uruguay |

JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2018 |

Albania, Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Australia, Austria, The Bahamas, Belize, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, China, Costa Rica, Grenada, Hong Kong (China), Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Marshall Islands, Macao (China), Malaysia, Monaco, New Zealand, Qatar, Russia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Samoa, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Sint Maarten, Switzerland, Turkey, UAE |

JURISDICTIONS THAT HAVE NOT INDICATED A TIMELINE OR THAT HAVE NOT YET COMMITTED |

Bahrain, Cook Islands, Nauru, Panama, Vanuatu |

The US has indicated that it will be undertaking automatic information exchanges pursuant to FATCA from 2015 and has entered into IGAs with other jurisdictions to do so. The Model 1A IGAs entered into by the US acknowledge the need for the US to achieve equivalent levels of reciprocal automatic information exchange with partner jurisdictions. They also include a political commitment to pursue the adoption of regulations and to advocate and support relevant legislation to achieve such equivalent levels of reciprocal automatic exchange.

The Berlin signing

We had already developed the idea of a multilateral competent authority agreement in the report we submitted to the G8 leaders as a means of facilitating and further standardising implementation. Given the political expectations on timelines, using an approach that would have amounted to a full international treaty (or treaties) for all signatory countries was not a viable option. So we had to move away from the approach used for the FATCA IGAs. Also we already had a convention endorsed by G20, the OECD and the Council of Europe that allowed for automatic exchange: the Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (the Convention). Importantly the Convention allows for both bilateral and multilateral competent authority agreements.

|

Going down the bilateral competent authority route not only risked deviating from the "one single standard approach" but the number of agreements to negotiate would have been staggering: for example, the 51 jurisdictions that signed in Berlin in only five minutes, would have otherwise required 1,275 separate negotiations. Interestingly, the competent authority agreement is designed as a framework agreement which achieves standardisation, but otherwise leaves flexibility and control to the signatories.

The G5 effectively launched this process and helped drive it, which also explains why the G5 Finance Ministers hosted the Berlin signing event and were on the panel during the press conference.

The involvement of the business community

A big part of the CRS relies on financial institutions: they are in the frontline of implementation and it would have made no sense to develop the CRS without consulting them. Some important points that changed in the process in response to business input included, for instance:

simplifications in the due diligence process;

a streamlined indicia search;

allowance for a wider use of publicly available information;

a number of options including for a less burdensome rule for new accounts of existing customers; and

provision for a wider approach to allow for a more efficient due diligence process.

Close consultation with business also remains a key priority going forward. Financial institutions are first in line with implementation, and especially those operating in multiple jurisdictions will notice first should inconsistencies arise or should guidance be lacking. There is a joint interest here to ensure that what starts as one standard stays one standard.

| The key people This was a huge team effort, but some people stand out. It is probably fair to start with the person who chaired the group and got countries to agree, Armando Lara Yaffar from Mexico and a well-deserved entry in International Tax Review's Global Tax 50 in 2013 and 2014. And, of course, Pascal Saint-Amans, Director of the Centre for Tax Policy and Administration at the OECD. Philip Kerfs in my team, who is now leading the ongoing work, Jorge Correa and Stephanie Smith did a lot of the thinking, drafting and much else. Much credit also goes to the UK Treasury team, and in particular Peter Green and Radhanath Housden for powering the early adopter process. And a big contribution was made by the Italian EU presidency, especially David Pitaro, who led probably the fastest ever adoption of an EU directive all the while ensuring that it remained consistent with the global standard. Finally we may not have reached the finish line without Keith Lawson, chairman of the business advisory group (BAG), and early input from Michael Plowgian then at US Treasury. |

The 2015 CRS pipeline

The focus is on implementation. The standard is new for everyone and the timelines are ambitious. If we get it right in the first place, we simplify significantly the peer review process which the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes has been tasked to do, saving costs for both business and governments. We focus a lot on training and keeping countries connected and coordinated as they, for example, draft legislation and issue guidance, so that what starts as one standard stays one standard.

We did our first foundation training in Mexico in December and just had the first advanced training in Berlin where we also brought in business, as the implementation process cannot happen without financial institutions. The events are already oversubscribed and several more will happen around the world later in the year.

These events, together with our discussions with business and other stakeholders also inform whether we need to produce additional guidance. You should also expect to see a CRS portal later this year which will contain relevant information, including information on Taxpayer identification Numbers (TINs) to help financial institutions operate the CRS. There is also close cooperation with colleagues in the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes as they move forward with the peer review process and the assistance they provide to members, and in particular developing countries. Finally, after Switzerland's signing of the multilateral competent authority agreement in November 2014 we expect more signatures in 2015 and may also have further signing events in support of this. There is an obvious efficiency gain the more jurisdictions join the same instrument.

Key challenges

Key challenges for governments include getting the implementation right and doing so with enough time for business to have the necessary systems up and running when the CRS goes live. Another key priority for governments is to protect the confidentiality of the information and to use it effectively in their compliance processes. The information is highly sensitive and we need to make sure it is only exchanged where confidentiality and data safeguards are respected both in law and in practice.

At a collective level we need to make sure that we have consistent implementation so we retain the consistency and logic of one global standard for the benefit of both governments and business. This also means ensuring that differing levels of implementation do not allow economic distortions undermining a level playing field so essential for the success of this process. This will be a key task for the peer review process.

For financial institutions it means:

overcoming "FATCA fatigue";

getting budget approved;

determining their status (as it may not be the same for FATCA and the CRS);

reviewing and modifying on-boarding procedures, involving the legal department; and

having early and close involvement of the IT function which will be key in any successful CRS rollout.

Given the scale of the project, advisers will play a key role and they are increasing both focus and capacity in this area, something that will certainly be needed.

The OECD's TRACE project

With the CRS we have developed a common standard for residence country reporting. Now we are committed to resuming work on TRACE (Treaty Relief and Compliance Enhancement), the common model for withholding tax relief at source that was developed by the OECD together with the financial sector. Both systems rely on the same stakeholders and are based on the same infrastructure and technical solutions. Combining both systems increases overall efficiency and reduces costs to all involved. Work on TRACE has started and is focusing on aligning TRACE to the CRS to maximise efficiency gains. There continues to be strong support for TRACE including from business. Of course, many commentators make the point in connection with the consultation on BEPS Action Item 6 on treaty abuse.

The fit into the larger OECD/G20 tax agenda

The world is becoming increasingly connected and transparency will continue to figure high on the political agenda. This applies to financial account information, but of course we are also working on:

country by country reporting (under Action 13);

the mandatory spontaneous, or put more simply, "automatic" exchange of certain rulings (under Action item 5) of the BEPS action plan; and possible disclosure obligations (under Action 12).

We need to keep a balance to avoid flooding tax administrations with data and overly burdening business. Tax administrations will also need to make effective use of the information they receive – an area where much work is underway. But more generally it means that any planning that would fail on a full disclosure basis is about to go out of business.

Achim Pross (achim.pross@oecd.org), head of the International Cooperation and Tax Administration division of the Centre for Tax Policy and Administration at the OECD