Commencing in late 2014 and continuing through 2015, the three liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants in Gladstone, on Australia's east coast, began the production and export of LNG to markets in Asia and around the globe. These are the first operational coal seam gas (CSG) to LNG projects anywhere in the world. Australia now has four operating LNG projects and a further six are under construction (both CSG-sourced and conventional), with an estimated AUD 200 billion ($147 billion) worth of investment in the Australian LNG sector. Australia is already the world's third largest exporter of LNG, and when all projects are on-line Australia is likely to become the world's largest LNG exporter.

The transition from construction to production may cause major changes in the operations of Australian LNG producers as they move from focusing on construction issues, budget overruns, and delayed deadlines to the business of extraction, processing, maintenance, and supply chain management.

Given that the vast majority of the capital invested has been foreign sourced, and that Australian LNG projects generally rely on the involvement of foreign-owned participants, what are some of the immediate and future issues for this industry from a transfer pricing perspective?

Under construction

Over the past few years, the primary focus of the onshore LNG projects in Australia has been the drilling of thousands of wells and the construction of aggregation assets, transport pipelines, LNG processing plants, and related infrastructure. At the same time, the operators' global focus has been on formalising customer sales contracts and ensuring that downstream assets are well positioned.

Unlike some other countries, Australia did not have any existing infrastructure such as pipeline or processing assets that could be repurposed into gas projects. Thus, the Australian projects have required construction from the ground up. All of this has involved significant construction of plant, labour, and capital. The operators have been placed under increasing pressure as completion deadlines have passed, budgets have run over by billions of dollars, and oil prices has fallen.

One area of focus has been the sourcing of long-term financing for projects with long lead times in actual revenue, and potentially profits. Depending on the scale of the project, financing needs may range between AUD 3 billion and AUD 25 billion. A large amount of the funding is sourced from related parties of the joint venture partners or, due to the substantial capital required, via syndicated loans.

Setting the terms of this financing and the associated pricing can be different from a typical loan arrangement. For example, interest deferrals may be built into the agreements to try to match eventual interest payments to actual revenue streams. Credit rating processes may become complex procedures that use various forecasting and pricing models to determine the project's risk profile across the life of the facility and the projects' different lifecycle stages. Using simple credit rating tools, or relying only on historical audited financial information, could provide anomalous results, which would in turn result in poor credit rating estimates for the facility. However, a review of the project's forecasts over the life of the facility may show that risk profiles fluctuate depending on the project status. Similarly, some ratios may become less important; for example, interest cover in years when interest is deferred. The transfer pricing challenges associated with these financing arrangements can be considerable, and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has been actively undertaking reviews.

Because the east coast onshore projects are considered unconventional (the gas is sourced from trapped reserves in coal seams), there has also been a significant investment by both the project participants and the associated service providers on the sourcing of people and expertise applicable to the specific requirements of extracting CSG. Large numbers of people with experience in the oil & gas industry globally have been brought to Australia to apply and develop their knowledge in a CSG context. Similarly, processes, production designs, and other intangibles have been brought to the country and in some cases redesigned to meet the requirements of the Australian landscape and the pure methane content of CSG-based LNG produced by the east coast projects.

Project overruns and cash deficits may cause project stakeholders to try to improve their supply chain, including the potential sell-off of certain assets, such as pipelines, power assets, processing plants, or potentially in the future, storage assets. This may bring the structure of the Australian onshore LNG industry closer to that of North America, where companies focus on an area of expertise within the supply chain rather than on an end-to-end project. The transfer pricing issues associated with such restructures can be challenging, depending on the circumstances, and the ATO maintains a strong focus on business restructures and the potential tax risks associated with them.

A shift to processing

With the construction phase winding down, and the production phase not yet in full swing, at the time of writing this article, only one onshore project has successfully shipped LNG. The projects are looking at their ongoing requirements for construction and engineering staff, and planning for the staffing and asset requirements of maintenance and ongoing drilling. The many service providers to these projects are also redeploying staff to large projects on the west coast of Australia or elsewhere in the world. In some cases, this shifting of people, in particular offshore, could give rise to the exit of intangible property, or as with asset sell-offs, could be a point of interest for the ATO as a potential business restructure. Companies should be aware of the rules in Australia, which can impute an exit charge on the business changes.

With the projects beginning to book revenue and/or look toward profitable years, these companies may start making financing repayments. In some cases, financing arrangements put in place during the projects' exploration or initial development stages have reached the end of their term and require refinancing, often with a very different risk profile now that exploration and construction are largely complete.

With the commencement of production, projects also become potentially liable for payments under both the state-based royalty programme connected to their licensing arrangements and the federally applied Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT). While both these liabilities entail domestic payments, the calculation is based on the value of the commodity – the CSG – close to the point of extraction rather than on the export price. Because the projects are integrated, it is difficult to find a price at that point in the chain, and transfer pricing principles are applied in this domestic scenario to assess the value on which liability is based.

Export and pricing

LNG projects may be subject to increasing scrutiny from the ATO as they move into production. The energy sector is already receiving attention from the Australian Senate's Economic Reference Committee's Inquiry into Corporate Tax Avoidance, which in July 2015 sent letters to eight energy companies requesting details of their international dealings and structures, and requiring them to present evidence to the committee in August 2015. The wide ambit of Australia's transfer pricing laws means that they cover not only sales to commonly owned offshore marketing hubs but also potentially sales to customers who are upstream equity holders, even when that equity holder does not have a controlling interest. The majority of the exported product has been pre-sold in long-term contracts, say of 15 or 20 years, to the equity investors in the LNG projects and other third-party buyers.

Long-term sales contracts are not uncommon. Often, committed contracts for the sale of a significant portion of LNG production are required by financiers to show the viability of a project that absorbs such large amounts of capital, with the attendant uncertainties of major long-term construction activities. This requirement to achieve funding means that many of these long-term sales contracts were agreed to five or more years ago. However, recent market changes (for example, oil price volatility, impending new supply from the US, displaced US imports now looking for customers, the emergence of buyers' clubs in Asia) are in turn driving changes to how future LNG contracts and pricing will be structured.

Basis of pricing

Export LNG is not necessarily priced like other resource commodities. First, there is the basis of the price. Export LNG is not, and has never been, a traded commodity with a publicly available list price.

For this reason, LNG contracts were often agreed with reference to LNG's "cousin", oil. For sales to Asian markets, this may have meant starting with the Japanese customs-cleared (JCC) crude, referred to as the Japanese Crude Cocktail. Sales to other markets may have been based on other oil indices such as the Brent Crude price. This allowed players to use oil price forecasts to predict where the price for LNG was going to go.

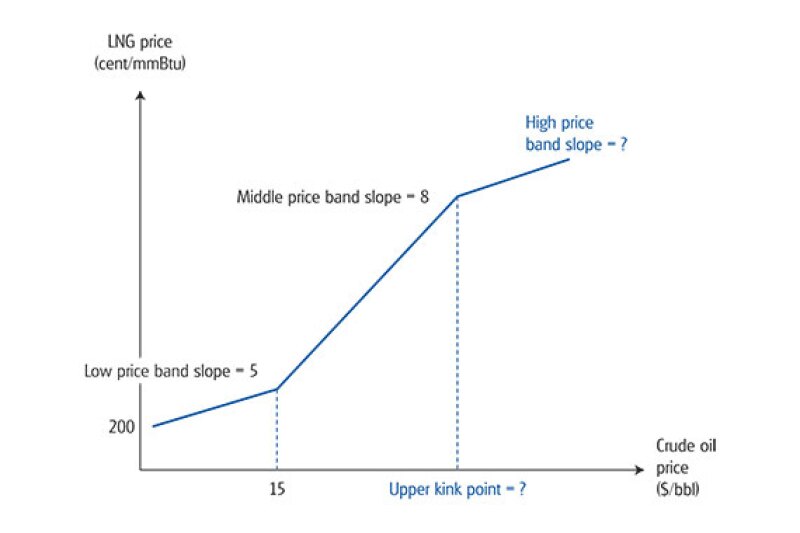

Pricing in LNG contracts is often agreed based on an S curve. The curve is a stepped pricing mechanism, where each step consists of a fixed component and a proportion of the referenced oil price. An S curve, when graphed against the oil price, is in the shape of the letter S (see Graph 1).

Graph 1: S Curve

Source: www.osakagas.co.jp

The overall price negotiated – that is, the outcome from the S curve – likely does reflect the buyers' and sellers' views of the quality of the product and the other terms surrounding the sale. However, the fixed component is not necessarily linked to the capital spent to produce, and the proportion of the oil price may not necessarily reflect the energy content of the LNG. The pricing components actually reflect the requirements of the negotiating parties, the competitive nature of the LNG market, and are based solely on the negotiating powers of the buyer and seller. In many cases, these S curves are negotiated under long-term contracts with price renegotiation available after a period of time, say five years. This becomes important in the evolution of gas contracting.

It is very difficult to find external information for comparable purposes relating to LNG pricing, largely due to the commercially sensitive nature of the information in the contracts, and the relatively small number of contracts entered into, compared to other commodities. However, internal comparable information can often be found. This also generally removes some of the comparability issues arising from product differences. Comparability adjustments are often required. For example, many LNG contracts include DES (delivered ex-ship) transport terms, meaning the price should be considered for differences in shipping distances and port requirements. Similarly, the comparison of pricing on large-volume or long-term contracts (for example, 20 years) may need adjustment if used on mid-term contracts (for example, three years). As with most commodities, the use of a CUP requires consideration of differences in comparability, and may require making reliable adjustments to account for these differences.

The evolving market

In the period since these initial long-term contracts were signed, the global market has changed rapidly, with a significant volume of potential export gas supply available from the US shale gas reserves, most likely at a very competitive price point. This changes the global supply and demand equation.

The increasing supply has brought new intermediary players into the market; the portfolio market players. These are companies that enter into contracts to buy large amounts of production and then use this to run a portfolio of product that is sold across long-term and mid-term contracts, and the short-term spot market. This allows the portfolio player to earn a profit by enhancing the use of its product portfolio across the different contracts and to benefit from movements in pricing.

LNG storage is also becoming an important factor for portfolio players and other buyers. Storage allows a party to buy product at a low price, for example, in summer when demand is lower, store it and then resell it at a much higher price to cover its costs of storage and still make a profit. No storage assets have been constructed in Australia yet; however, new storage has come on-line in Singapore, for example.

Another change is buyers' preference to move away from long-term supply contracts to more mid-term or spot arrangements. This is consistent with changes that have also been seen in coal and iron ore sales to Asia and could be a major change in the structure of the LNG sales environment. With extra capacity coming into the market, and a volatile oil price, buyers may not wish to commit to long-term supply at a high price when there could be potentially lower-cost product on the horizon. Portfolio payers may be able to bridge the gap between producers and customers in this case, which further shows their importance in this new type of market. It is not yet clear what effect this change will have on the ability to secure financing for future greenfield projects.

Demand for LNG is expected to continue to increase, particularly when prices drop as a result of increased supply. Given the number of existing and planned additional re-gas plants in China coupled with anticipated utilisation increases, countries like China will be able to grow their LNG usage at a rate that should keep up with the increase in supply. However, portfolio and marketing players will be important to match the quality of product with the right buyer.

Export contracting and pricing in the future

When looking at gas contracting in the future, portfolio players likely will continue to play an important role.

Similar to Japanese trading houses, portfolio players bridge the gap between buyers' and sellers' expectations.

Gas may well be the major energy source of the future, as technology improves its substitutability for other energy sources. Upstream players need to ensure they are carefully structuring marketing and shipping and other value-adding downstream functions. As with the movement of other commodities in the past, the LNG market is set to become a market where players with access to data and market insights will be able to enhance their use of product and see favorable profits in their supply chain.

With an increase in the liquidity of the LNG market, it is likely that at some point in the future a separate export list price will become available. This may not be a short-term outcome but, over time, as LNG players wish to be less at risk on oil price volatility, this becomes more likely. The question is, where could central trading point (and associated reference price list) be based? Shanghai may be a viable proposition, considering its access to both domestic and international markets, the volume of domestic gas consumption, and strong trading markets. Singapore is also a possible location, with its strong commodity marketing, financial and shipping industries, and new storage facilities.

When looking at the Australian industry and the global market, producers, marketers, and customers will need to understand the swiftly and likely continuously changing market realities for LNG.

|

|

John BlandPartner, Transfer Pricing Deloitte Australia 123 Eagle St. Brisbane, Australia 4000 Tel: +61 7 3308 7275 John Bland leads Deloitte Australia's Queensland transfer pricing team and brings a wide range of transfer pricing experience combined with a focus on energy and resources sector transfer pricing issues. He has 30 years of taxation experience, including 10 years in the ATO and 17 years as a dedicated transfer pricing specialist with Deloitte. John is a key member of Deloitte's national transfer pricing energy and resources industry group, focusing on all aspects of energy & resources transfer pricing issues. John's recent and current engagements include, but are not limited to, leading the first Australian onshore CSG advance pricing arrangement (APA) project (currently underway), assisting clients in their development of appropriate tax-effective transfer pricing structures for high risk global mining exploration and development activities, including foreign gas exploration and development activities managed from Australia, and advising on the development of pricing models to support the arm's-length pricing for upstream and midstream funding transactions into major Australian CSG projects. |

|

|

Emily FalckeDirector, Transfer Pricing Deloitte Australia 123 Eagle St. Brisbane, Australia 4000 Tel: +61 7 3308 7383 Emily is a director in Deloitte's transfer pricing group, based in Brisbane, Australia. She has fourteen years of transfer pricing experience in offices in London, Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Emily provides transfer pricing services to large multinational corporate groups in a number of sectors, with a specific focus on the energy and resources industry. Within the industry, Emily has provided assistance to clients in tax authority audit and risk review processes, APA and competent authority negotiations, treatment of permanent establishments (including shipping), pricing for trading houses and marketing hubs, commodity pricing across a number of commodities for both domestic and international purposes, mineral and petroleum rent tax implementation and compliance, pricing for financing on large projects. |

|

|

Geoffrey CannPrincipal, Consulting Deloitte Australia 123 Eagle St. Brisbane, Australia 4000 Tel: +61 7 3308 7125 Geoffrey Cann is the national director for Deloitte Australia's oil & gas industry group and is based in Brisbane. He focuses on helping oil & gas companies address their growth, talent and productivity challenges. He has 25 years of management consulting experience, gained through engagements in Canada, Australia, the US, Hong Kong, China, Japan, Korea and the Caribbean. Geoffrey holds numerous publications to his name, presents regularly on strategy topics and has been a guest lecturer at the MBA programme at the Haskayne School of Business at the University of Calgary. |