The final cost sharing regulations published in 2011 introduced a new set of "commensurate with income (CWI)" rules, described in Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(i)(6) Periodic Adjustments.

In a cost sharing arrangement (CSA), if participant A makes a platform contribution (X) to the CSA, other participants are required to make a platform contribution transaction (PCT) payment to A for X. If the actually experienced return ratio (AERR) for those PCT payments is outside the periodic return ratio range (PRRR), which is 0.667 to 1.5 for those taxpayers who have "substantially complied" with the Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(k) administrative requirements (and 0.8 to 1.25 for those who have not), then the commissioner of Internal Revenue may make a periodic adjustment to other cost sharing participants' PCT payments to A.

The final cost sharing regulations include detailed guidance on the mechanics of how AERR and PRRR should be calculated, including the adjusted residual profit split method, but provide no substantive and direct linkages to reconcile the CWI rules with the arm's-length standard regarding the choice of approach and parameters. This article provides a general conceptual framework to discuss how different valuation methods relate to CWI rules, and demonstrates that a variant of a specific valuation approach, known as the venture valuation model, can resolve some of the challenges that arise in the context of applying CWI rules.

Valuation approaches

There are three key valuation approaches available to analysts and tax practitioners: the certainty equivalent (CE) approach, the cost of capital (CC) approach, and the venture capital (VC) approach. In addressing the central question of determining the value of an investment, these valuation approaches differ in how they treat (and measure) time value of money and risk, when risk can be further split into project risk and market risk.

Time value of money reflects the opportunity cost of time, and compensates the investor for trading off today's, versus tomorrow's, access to the invested capital. Time value of money is often represented by the risk-free rate rf, which converts tomorrow's unit of value into today's unit of value, at no risk.

In addition to intertemporal tradeoffs, investment opportunities are subject to risks. In that context, risk is broadly defined as the possibility of different (future) realisations and circumstances that determine variability in the future value of the investment and ultimately affect its current value. Some risk, often referred to as project risk or diversifiable risk, can be fully insured or hedged against; that is, combinations of alternative investments perfectly offset the changes in value in all future realisations of a given investment. Therefore, an investor is guaranteed a constant future value in all world jurisdictions by combining all such investments. Specific risk is commonly identified by the distribution of possible realisations and their associated probabilities of a single investment opportunity (for example, probabilities of success and failure of a project). Unlike idiosyncratic risk, the second type of risk relates to market or systematic risk, which is the risk that arises from the interaction of the investment with the market in aggregate, the result of which cannot be diversified away. Market risk is routinely identified by the amount of compensation the investor requires under market conditions for taking on additional risk over and above the risk-free rate, termed risk premium.

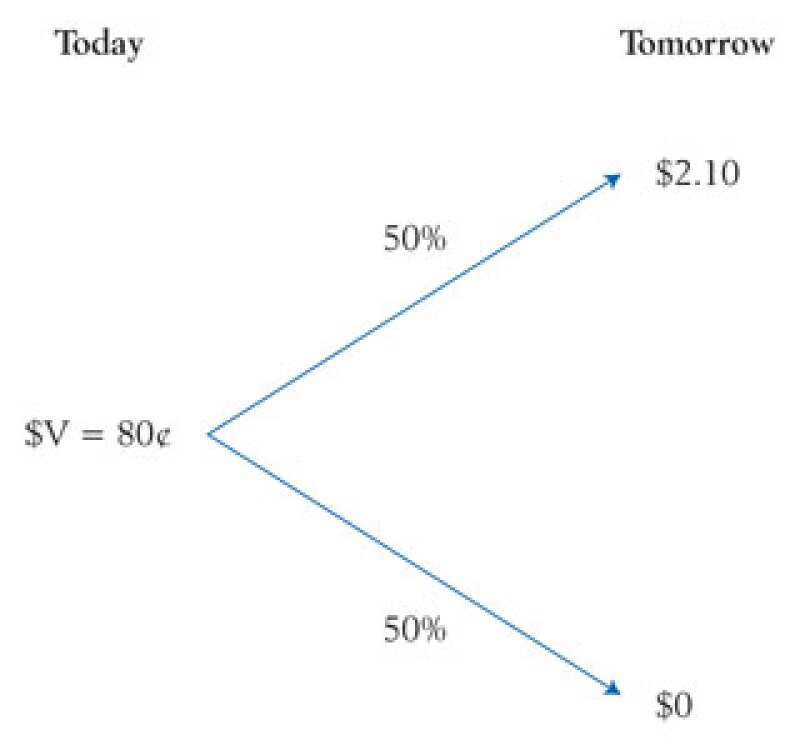

To keep things simple and illustrate how the CE, CC, and VC approaches deal with time and risk, we consider a stylised investment opportunity that has equal chances to cash out $2.10 or $0 tomorrow to the investor and is currently traded at price (or value) $V = 80¢. The figure below provides a schematic of this investment opportunity (or PCT, when discussing this example in the context of a CSA).

All three valuation methods are forward-looking and assume the same amount of information is available to the analyst and parties to the transaction, but they use different inputs in their reconciliation with the market, arm's-length price. Table 1 shows the breakdown of the inputs for each approach and the associated numerical example based on the investment schedule discussed above.

Table 1 |

|||

Approach |

Formula |

Valuation elements |

Denominator adjustment |

Certainty Equivalent (CE) |

$CE certainty equivalent of investment rf risk-free rate |

Time |

|

Cost of Capital (CC) |

$EV expected value WACC is the weight average cost of capital of the investment |

Time and systematic risk |

|

Venture Capital (VC) |

$Success represents the expected value of the investment at the time of a successful exit M is target multiple of money on the investment |

Time and risk |

|

The CE approach reduces the valuation problem to convert the expected (probability-weighted) cash flows so that the investment is remapped into a risk-free stream of expected returns. In the formula, all risk adjustments are done and accounted for in the numerator (first by calculating the expected value of the investment and second by scaling down the expected value by a certainty equivalent factor) while time value of money is taken care of in the denominator. In the example, the expected (probability-weighted) cash flow of $1.05 is scaled down by a factor of 0.8, which reflects the market-risk attitude of the investment and discounted by the risk-free rate of 5%.

The CC method, used by most companies and tax practitioners, calculates the value of an investment by discounting the expected cash flows by a discount rate adjusted for systematic risk. In the formula, only diversifiable risk is accounted for in the numerator, while time value of money and systematic risk are taken care of at the denominator by the discount rate incorporating the risk-free rate and the risk premium. In the example, the expected (probability-weighted) cash flow of $1.05 is discounted by the (risk-adjusted) weighted average cost of capital (WACC) of 31.25%, which reflects a market risk premium for the investment of 26.25% = 31.25% - 5% over and above the risk-free rate of 5%.

The VC approach values the investment based on a value multiple that measures how many dollars an investor expects in return for every dollar invested in the project at the time of a successful exit, which in the VC context is typically considered to be an initial public offering (IPO) or equivalent payoff event. The target multiple in our example of 2.625 reflects the time and risk reward required to invest 80¢ in the project when the investor anticipates $2.10 in a successful exit. Note that when the target multiple is converted into a discount rate in the example, the resulting VC discount rate of 162.5% incorporates the time value of money and the total risk adjustment for this investment, where total risk includes both systematic and idiosyncratic risk. Arguably, the total risk premium of 157.5% = 162.5% - 5% arising from the VC approach is comprised of a market risk premium of 26.5%, as in the CC approach, and a project risk premium of 136.25%.

The VC approach

The key advantage of the VC approach is that it disassembles the valuation problem into two simple inputs: the expected value of the investment at the time of a successful exit and the target multiple of money on the investment.

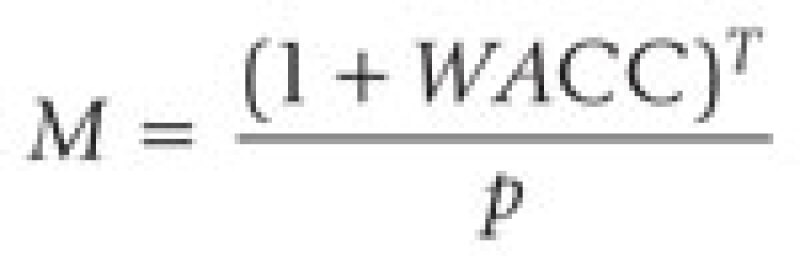

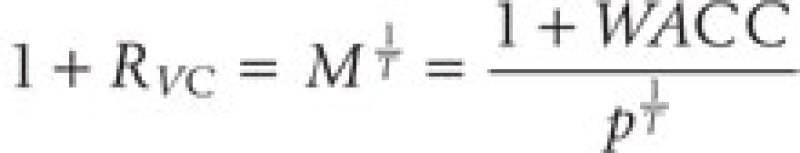

While it is beyond the scope of this article to fully elaborate the VC approach, suffice it to note that a wide range of techniques is employed for the estimation of exit values and target multiples. Broadly speaking, exit valuations are estimates of the investment at some time in the future and contingent upon a specific event (a successful exit). Therefore, a reliable application of the VC method depends on the definition and measurement of successful exit and should be the subject of careful analysis by any analysts adopting this methodology. As a practical matter, a central idea of the VC approach is to ignore (or make first approximations of) lesser payoffs and focus on contingencies when the payoffs are significant or relevant to the investor. Therefore, in a VC method valuation target returns are measured against successful investments and only the successful cases are considered, with unsuccessful failure cases given an effective value of $0. Because of this representation, target multiples are the combined leverage of three elements: the probability of successful exit, p, the expected time of successful exit (with no further rounds of investment), T, and the weighted average cost of capital of the investment, WACC, as illustrated by the following simple formula:

with the resulting discount rate, RVC, implied by the valuation multiple from the VC approach:

Note that in the example the time horizon simplifies to T = 1. This formula clearly shows how the VC approach incorporates all elements of time and risk when valuing investment opportunities contingent on success. It also shows that RVC > WACC whenever the probability of success is not 1. Put differently, to the extent there is project risk, the VC discount rate must be higher than the WACC.

Arm's-length standard and CWI rules

The connection of returns, expected returns, and net present value (NPV) of expected returns with the three valuation methods discussed above in the context of applying the arm's-length standard and CWI rules, in their specification under Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(i)(6) Periodic Adjustments, is crucial to the transfer pricing practitioner. In a nutshell, two moments in the valuation and CWI testing process can be distinguished in the context of a CSA:

A) Before and after the PCT, when each party holds different expected returns but the transaction leaves each cost sharing participant no worse off, with no lower NPV of expected returns.

B) Before and after the uncertainty/risk realisation when cost sharing participants (after the PCT) may experience actual, realised returns different from expected returns.

As stated in Treas. Reg. §1.482-1(b)(1) "[a] controlled transaction meets the arm's length standard if the results of the transaction are consistent with the results that would have been realised if uncontrolled taxpayers had engaged in the same transaction under the same circumstances (arm's-length result). However, because identical transactions can rarely be located, whether a transaction produces an arm's-length result, generally, will be determined by reference to the results of comparable transactions under comparable circumstances." In short, the arm's-length standard relates to point A above. In the example, 80¢ is an arm's-length price for the investment opportunity, and all three valuation approaches discussed above provide a coherent and internally consistent framework to support this conclusion.

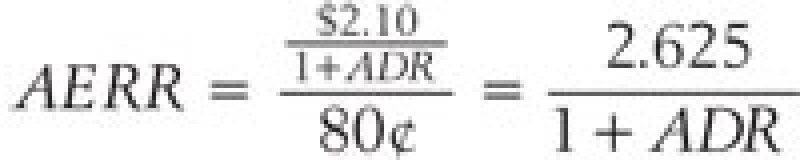

Under Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(i)(6), the periodic adjustment rules refer to actual, realised returns, and therefore are linked to point B above. What would happen if we were to test the AERR when the investment is successful in our simple example? The (simplified) AERR test would check the following ratio, where "ADR" stands for the applicable discount rate:

Based on the discussion presented above, it should now be apparent that to provide a correct NPV calculation, (1 + ADR) must be equal to the VC multiple M, resulting in an AERR of 1, as expected given that the PCT price is at arm's-length by construction.

It should be noted that while references to discount rates other than the one implied by the VC approach are present in the final CS regulations, (PCT Payor WACC) in discussing the ADR Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(i)(6)(iv)(B) allows for great flexibility in the choice of input based on facts and circumstances: "However, if the Commissioner determines, or the controlled participants establish to the satisfaction of the Commissioner, that a discount rate other than the PCT Payor WACC better reflects the degree of risk of the CSA Activity as of such date, the ADR is such other discount rate." See also Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(i)(6)(i). Applying different discount rates to the AERR calculation would lead to a mispricing of the realised investment and therefore incorrectly compare the value of the realised investment and the value of the PCT. Specifically, because investments (and PCT in the context of CSAs) generally carry significant project risk, using estimates of the risk-free rate (as in the CE approach) or the WACC rate (as in the CC approach) would systematically overvalue the realised investment and overestimate the AERR (in the example, respectively resulting in AERRs of 2.5 and 2, well above the PRRR) and more likely to trigger the PCT periodic adjustment. Note that additional considerations relating to exceptions to the periodic adjustments rule may be applicable, depending on the facts and circumstances of the PCT under analysis. See Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(i)(6)(vi) and Joseph Tobin, "2011 Cost Sharing Regulations: Probability Weighted Projections and Periodic Adjustments," mimeo (November 2013), for further discussion on the applicability of the periodic adjustments mechanism.

Conclusion

In the normal course of business, the existence of realised returns in excess of (or below) expected returns provide tradeoffs and incentives for investors to operate in active markets by exchanging and allocating risk in arm's-length transactions. To support the process of valuing such transactions, analysts have developed numerous techniques that identify and measure the key price determinants, such as time value of money and different forms of risk. Since the introduction of the final cost sharing regulations, some tax practitioners and commentators have raised concerns that the CWI rules under Treas. Reg. §1.482-7(i)(6) could be in potential conflict with the arm's-length standard and inconsistent with any sound models.

In this article we briefly outlined the three main NPV-based valuation methods available to tax practitioners and valuation analysts, and provided a general conceptual framework to illustrate how to reconcile the periodic adjustments rules with sound valuation principles and the arm's length standard by applying a variant of a specific valuation approach, known as the venture valuation model.

Biography |

||

|

|

Marco FiaccadoriManager, Washington National Tax Deloitte Tax LLP Washington, DC Tel: +1 202 758 1407 Email: mfiaccadori@deloitte.com Marco Fiaccadori is a senior manager in Deloitte Tax's Washington National Tax office. He has been part of Deloitte's global transfer pricing and international tax group since 2008. Mr Fiaccadori has extensive experience in company financial and quantitative research analysis and industry data. He has prepared economic analyses of intercompany pricing strategies, and assisted with transfer pricing planning, documentation, and competent authority negotiations for multinational companies in a wide range of industries. Mr Fiaccadori has managed and coordinated transfer pricing projects involving business restructuring and intellectual property portfolios for global clients in the media and technology, pharmaceutical and medical equipment, lodging and hotel, automotive, and branded consumer products industries. He is responsible for the economic analysis and the day-to-day management of advance pricing agreements and cost sharing arrangement for global clients with local operations in the Americas, EMEA, and APAC regions. Mr Fiaccadori earned his PhD at the Department of Economics of the University of Chicago, where he was also a lecturer in economics at the College before joining Deloitte. Education PhD in Economics, University of Chicago MA in Economics, University of Chicago BA in Economics, Bocconi University |

Biography |

||

|

|

Arindam (Arin) MitraPrincipal and senior economist Deloitte Tax LLP Suite 400 555 12th Street, NW Washington, DC 20004 Tel: +1 202 879 5670 Email: amitra@deloitte.com Arin Mitra is a principal and senior economist based in Washington, DC. He co-leads Deloitte's business model optimisation (BMO) practice and leads the Washington office's transfer pricing team. Over the last 18 years he has practiced in Deloitte's offices in Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Sydney. Mr Mitra primarily focuses on complex BMO engagements related to the restructuring of intercompany transactions involving intellectual property, management and functional rationalisations, and supply chain rationalisations. He specialises in dealing with tax authorities on transfer pricing, including audits, competent authority negotiations, and advance pricing agreements (APAs). He has developed and negotiated transfer pricing methods for over 30 APAs, mostly bilateral, involving Australia, Canada, China, Japan, and the US. He has been recognised by Euromoney and the International Tax Review as a leading transfer pricing adviser in the US. Mr Mitra has advised companies across a wide spectrum of industries, including media, telecommunications and technology; pharmaceuticals and medical equipment; and branded consumer products in planning and documenting their transfer prices. He has successfully defended several clients in audits conducted by the tax authorities and has worked with attorneys from several leading law firms. Mr Mitra has published extensively on transfer pricing topics. He is a member of the American Finance Association. Educational qualifications and professional affiliations Brown University, Providence, RI, USA PhD in Economics, May 1994; MA in Economics, May 1991 Concentrations in Financial Economics and Applied Game Theory Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India MA in Economics (First Class), December 1987 The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI), New Delhi FCA – Fellow Member of ICAI, November 1986 Calcutta University, Calcutta, WB, India Bachelor of Commerce with Honors in Accounting, July 1984 |

Biography |

||

|

|

Philippe PenellePrincipal Deloitte Tax LLP Los Angeles, California USA Tel: +1 (213) 553 1994 Fax: +1 (213) 694 5480 Email: ppenelle@deloitte.com Philippe Penelle, PhD, is a principal with Deloitte Tax, specialising in business model optimisation (BMO) strategies and transfer pricing solutions for some of the firm's largest multinational companies. He joined Deloitte in 1998 in the Chicago office and transferred to the Los Angeles office in 2010. As the West Region Leader of Deloitte's intellectual property group, Mr Penelle leads a group of dedicated international tax and transfer pricing specialists in designing and implementing complex strategies to assist multinational companies structure their value chain functions (not limited to supply chain) and intellectual property holdings in a tax- and treasury-efficient manner. With more than 14 years of experience in the valuation of intellectual property for transfer pricing purposes, Mr Penelle has not only assisted his clients in developing and implementing efficient tax structures, he has also represented them before the Internal Revenue Service in advance pricing agreement proceedings and in audit defenses. He has extensive experience in the pharmaceutical, oil & gas, consumer products, and apparel industries. Mr Penelle is a regular external speaker, including at Council for International Tax Education (CITE) conferences, and the recipient of numerous presenter awards, including CITE's "Outstanding Star Speaker Award" in 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2011. He has published a number of technical articles on transfer pricing, as well as contributed a chapter to the Transfer Pricing Handbook published by John Wiley & Sons. Mr Penelle's most recent work includes three original technical articles commenting on the recently published US final cost sharing regulations. Two of these articles have been published in Bloomberg/BNA's Transfer Pricing Report; the third is under review and is forthcoming. Mr Penelle was a lecturer in Economics at the College (1994-1996) and then Assistant Professor of Economics (1996-1998) at the University of Chicago before joining Deloitte in 1998. He has received a number of academic awards, including the title of Aspirant of the Belgian National Sciences Foundation (NSF) and Fellow of the Belgian American Educational Foundation (BAEF). Mr Penelle earned his PhD in Economics from the Department of Economics at the University of Chicago in 1996, after earning a Master in Econometrics suma cum laude and a License en Sciences Economiques suma cum laude, both from the Université Libre de Bruxelles (Belgium). |