This article sets forth five indicia of beneficial ownership that should be the starting point of any transfer pricing analysis regarding intangibles. The identification of the beneficial owners should be completed before the quantitative analysis of the transfer prices.

Framework

We limit our discussion to what we call "commercialisable intangible properties", (CIP), which we define as any intangible that fits the definition in US IRC §936(h)(3)(B) and that could potentially be transferred between unrelated parties. The §936 definition generally includes patents, inventions, formulae, processes, designs, patterns or know-how; copyrights and literary, musical, or artistic compositions; trademarks, trade names, or brand names; franchises, licenses, or contracts; and methods, programmes, systems, procedures, campaigns, surveys, studies, forecasts, estimates, customer lists or technical data. An intangible attribute that cannot be subject to transfer between unrelated parties on a stand-alone basis would not be property and therefore should not be included in the definition of CIP. For example, informal know-how – know-how in the form of collective or individual experience of employees – falls into this category. It is never sold as intellectual property, but may be utilised to provide services. Nonetheless, a transfer of a portfolio of properties, or a business, may still be split into separate categories for analytical purposes only. For example, purchase price allocations split the value of a business deal among different categories, but this does not mean that each category defined for analytical purposes would constitute CIP.

Some CIP, such as patents or trade secrets, may be legally registered or protected; in those cases, multinational groups often prefer to carry the legal registration in the name of a group member that gives them the greatest advantage in potential litigation, as acknowledged in paragraph 73 of the Revised Discussion Draft on Transfer Pricing of Intangibles issued July 30 2013. In many cases, group companies do not go through the effort of documenting the separation between legal and economic ownership through formal license agreements. Besides the divergence of legal and economic ownership, many CIPs may not be subject to legal protection (such as certain aspects of know-how, or customer relationships) and may not have legal owners. This raises the issue of beneficial ownership (also referred to as economic or tax ownership).

This article proposes that there are at least five significant indicia of beneficial ownership: cash, capitalisation, conduct, control-executive, and control-operational.

A presumptive beneficial owner would be expected to meet most, if not all, the indicia, as explained below:

Cash. Assume upfront responsibility for all of the CIP's necessary development or acquisition costs. Did the presumptive owner put capital at risk?

Capital. Arrange reasonably adequate capitalisation upfront to withstand the potential failure of the development effort (instead of relying on future capital injections). Would it make economic sense for a company with the presumptive owner's resources to have attempted such a development project?

Conduct. Secure proper legal rights to the CIP and memorialise the intended course of conduct. Following through with the implementation of such course of conduct is also important. While the ultimate legal registrations may not be in the name of the beneficial owner, there must be some type of documentation of the initial intent regarding which party would be the beneficial owner. Has the presumptive owner made arrangements upfront and conducted development and commercialisation efforts in a consistent manner?

Control– Executive. Exercise managerial control over the business activities that directly influence the amount of income or loss realised from the CIP or their development. Did the presumptive owner set the budget, and make the strategic decisions for development, protection, and value preservation? These questions are consistent with the guidance provided in paragraph 79 of the Revised Discussion Draft on the Transfer Pricing of Intangibles.

Control – Operational. Exercise operational control over CIP development or commercialisation. Did the presumptive owner design the development programme and make the most of the critical operational decisions? Please note that Treas. Reg. §1.482-1(f) appears to suggest either managerial or operational control: "Exercise managerial or operational control over the business activities that directly influence the amount of income or loss realised." Hence our separation of the two aspects of control.

Among the five indicia above, the last two – executive and operational control – appear to be the focus of recent governmental efforts. They are challenging concepts for transfer pricing because the arm's-length principle is applied under a presumption of independence of the parties. To apply the presumption of independence, we should first determine who is the owner of the property involved in the transaction, and then apply the relevant methods. Conducting a transfer pricing analysis and the determination of beneficial ownership at the same time may cause some confusion.

Case study

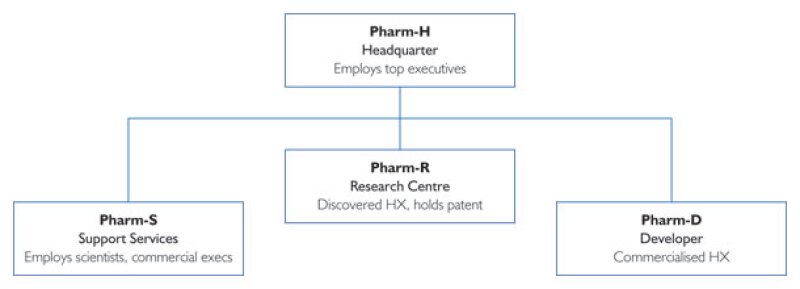

Our case study involves Pharm, an emerging biopharmaceutical company headquartered in Country H, with subsidiaries in three other jurisdictions:

R, where it conducts research;

D, where it does further development and eventual commercialisation; and

S, where it has support personnel (scientists and commercial people) helping with development and commercialisation.

Pharm's legal entity organisation chart is provided in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1 |

|

Pharm-R had been responsible for the underlying research and discovery of HX, a new therapy for a genetic disease. By 2010, Pharm-R's patent application in all major jurisdictions was accepted, and all preclinical work on HX was completed. At that time, Pharm did not have any presence in D or S. Chief executives working for Pharm-H have had oversight over all strategic decisions, secured funding for the enterprise, and provided equity capital for Pharm-R.

The first question to ask is whether Pharm-R is the bona fide beneficiary owner of the HX patent.

While this seems straightforward, application of the five indicia reveals some ambiguity:

Cash: Pass. Clearly, Pharm-R funded all the research.

Capital: Pass. The flow of funding for Pharm on a consolidated basis had been through competitive markets. However, a question comes up whether Pharm-H injected all incoming capital directly into Pharm-R. What if Pharm-H funded Pharm-R on an as-needed basis? This would be a concern only if Pharm-R had received external financing (debt or supplier payables) that it could not have satisfied had the development of HX failed.

Conduct: Pass. Pharm-H executives' fundraising is a shareholder activity and Pharm-R would not normally pay a service fee for that. Assuming the oversight by chief executives was in the form of stewardship and duplicative review, no service fee would normally be required. Notwithstanding the typical facts described above, an additional cautionary step would have been to execute a services agreement between Pharm-H and Pharm-R, and have Pharm-R pay a service fee for any operational support Pharm-H executives may have provided.

Control-Executive: Ambiguous. As in any multinational enterprise, all decisions are subject to approval by the chief executives who receive recommendations and support from their subordinates. It would be unreasonable to expect Pharm-R to have taken actions against the policies and directives of Pharm-H. Recognising that the raison d'être of a multinational enterprise is to centralise such executive decision-making, what would be the level of executive control one would expect in a subsidiary? We believe a reasonably independent corporate governance mechanism for a subsidiary may suffice. This would normally be in the form a corporate board and, depending on the nature of operations, a full-time director. The terms of reference of the corporate governance mechanism would be to confirm that the decisions taken by headquarters are consistent with the corporate interests of the subsidiary. In our example, the board and/or the director of Pharm-R should have been able to assess whether the research project selection and funding decisions would have been significantly different for Pharm-R in the absence of Pharm-H's controlling ownership interest. This would be a reasonable test of this index of beneficial ownership, but the rules on this point are still evolving.

Control-Operational: Pass. Pharm-R personnel conducted the research leading to the discovery of HX.

As HX launched into clinical development, Pharm started operations in Country D and Country S, and hired personnel there who would manage some of the clinical studies that would be conducted around the globe. The actual clinical studies would be run by independent contract research organisations, CROs, and the clinical study protocols would be designed by Pharm-R personnel, with some input from Pharm-D and Pharm-S employees. More of the employees are with Pharm-S than Pharm-D. However, Pharm-D secured an exclusive license for the HX patent from Pharm-R, assumed the funding responsibility for all clinical development, engaging Pharm-S and Pharm-R as contract research service providers. Pharm-D applied and secured all regulatory approvals and began selling HX around the world through related and/or unrelated distributors.

The second question to be posed is whether Pharm-D is the legal and beneficial owner of the right to sell HX on a global basis.

The answer is more complex than for the first question, with many ambiguities.

Cash: Pass. Clearly Pharm-D funded all the development, and pays the license fees to use Pharm-R's patent.

Capital: Pass. The same comments as in the first question apply.

Conduct: Pass. Pharm-D appears to have put in place all necessary agreements (patent license, service agreements, etcetera) in a timely manner.

Control-Executive: Ambiguous. Pharm-D's board reviewed all contracts with related and unrelated parties and approved their execution. The board also reviewed clinical development plans, which compounds to fund, which indications to pursue, how much to budget, and what endpoints to target during its periodic meetings, and issued guidance to Pharm-D officers about important matters to monitor when the board was out of session. However, these strategic decisions were all made by Pharm-H or Pharm-R personnel, with feedback from others as necessary. The critical test here is whether Pharm-D directors, or the board, have had opportunities to review these strategic decisions and their potential financial consequences from Pharm-D's perspective. If there is a corporate governance process that allows such a review and avoidance of excessive risk-taking by Pharm-D, this index of beneficial ownership would be satisfied. One important caveat should be kept in mind regarding the capabilities of the board and the directors of Pharm-D. It is expected that the board has the background and experience to be able to "make" the decisions they reviewed.

Control-Operational: Ambiguous. Unlike the analysis in the first question, Pharm-D's actual operational involvement in the development and commercialisation process, although significant, was not as substantial as Pharm-R's role in the research and discovery process. While Pharm-D personnel had some operational roles, it appears that most of the operational decisions, such as the design of clinical trial protocols, responses to adverse events, or the monitoring of the unrelated CROs were taken by others at Pharm-S or Pharm-R. Does this lack of operational involvement jeopardise Pharm-D's presumptive beneficial ownership? This issue may be approached on two levels: First, identify the types of operational decisions that can potentially be left to an outsourced service provider. Pharm-D's lack of involvement in such decisions would not normally jeopardise its beneficial ownership claim. Second, elevate the remaining decisions to the level of executive control and require a concurring review from the board or directors of Pharm-D. This would normally require an operational process to secure such a review on a timely basis.

Powerful tool

The framework presented in this article can be a powerful tool for reviewing the beneficial ownership of intangibles for transfer pricing purposes, before conducting an economic analysis of the pricing. The analysis of a relatively simple structure identifies challenging issues with respect to conflicts with the internal operations of a multinational enterprise when decisions are centralised to avoid duplication. While good practices at the subsidiary level corporate governance may address most issues, taxpayers may benefit from additional rulemaking to clarify the degree of due diligence and capability expected from a subsidiary's board and directors.

Biography |

||

|

|

Aydin HayriPrincipal Deloitte Tax LLP Washington National Tax Office Tel: +1 202 879 5328 Email: ahayri@deloitte.com Aydin Hayri is a principal in the Washington, DC office of Deloitte Tax. He is the life sciences industry leader for the transfer pricing practice, and manages our Philadelphia transfer pricing practice group. He has been with Deloitte since 1998. Mr Hayri assists clients with transfer pricing planning involving global and domestic intellectual property development and licensing strategies; and planning and implementation of supply chain and business model restructurings. He has provided thought leadership by developing and applying China and the Far East sourcing strategies, such as adjustments for manufacturing and distribution risk differences, and adjustments for recession, market share, and book-to-market value differences. In addition to the pharmaceutical industry, his experience covers the medical device, defense/aerospace, manufacturing, and retail sectors. Before joining Deloitte, Mr Hayri was an assistant professor of economics at Charles University, Prague; the University of Warwick, England; and a research fellow at Princeton University. His primary specialization was industrial organization, with emphasis on the economics of risk, uncertainty, and valuation. He taught courses on this subject, published articles in international journals, and obtained grants from the European Commission, the Economic and Social Research Council, and the World Bank. Mr Hayri still teaches occasional courses for MBA students. Education PhD, Economics, Princeton University MA, Economics, Princeton University BA, Economics, Bogazici University, Istanbul Selected transfer pricing publications

|

Biography |

||

|

|

Darcy AlamuddinDeloitte Tax LLP 111 S. Wacker Drive Chicago, IL 60606 Tel: +1 312 486 2049 Email: dalamuddin@deloitte.com Darcy Alamuddin is a principal in the Chicago office of Deloitte Tax's transfer pricing practice. With 18 years of experience, Darcy provides multinational clients with tax consulting services on many aspects of transfer pricing and international taxation. Darcy has worked on a wide variety of transfer pricing issues that include planning, strategy review, audit defense, and documentation engagements. In the context of these engagements, she works with clients in the areas of structuring, tax minimisation, and foreign tax credit planning. Her projects have covered headquarters services, inbound and outbound tangible product transactions, outbound migration of intangible product transactions, licensing of intangible assets, business model optimisation projects and the provision of contract R&D and trading services. Darcy has served French, German, Japanese, UK, and US multinational corporations. Specifically in respect to headquarters services projects, Darcy has performed 15 to 20 of these headquarters studies for various clients. The results of these studies have supported service fees to be changed a quantifying the service fee amount as part of a bundled system royalty. Additionally Darcy has suggested these changes with great success in local country audits in the US, UK, Canada, Germany, etcetera, with the creation of local country reports. Darcy has spoken at seminars on both international tax and transfer pricing. Her seminars on international tax have addressed topics such as global earnings mobilisation, the taxation of intellectual property, the allocation and apportionment of interest expense, and Subpart F. She has spoken on European, Japanese, South American and US transfer pricing issues in Japan and the US. Darcy's seminars have been sponsored by, among others, ATLAS Information (US), Interstate Tax Report (US), Global Education Services (US), Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (US), and the Mitutoyo Corporation (Japan). Last year Darcy was accepted into the IWF Leadership Foundation which selects exceptional emerging women leaders from the corporate, government, academia, and the non-profit sectors for its acclaimed Fellows Program, a year-long intensive training programme. Darcy was one of 35 rising women leaders from 14 nations selected, making it the largest and most competitive pool of candidates in Fellows Program history. Darcy holds a BBA and JD-MBA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. |