When German author Kurt Tucholsky wrote about the opposite of good not being evil but good intention he could not have known about the European common market and was definitely not referring to VAT issues arising from intra-Community trade. Nonetheless, his quote seems to well apply to the latest developments in Germany concerning the introduction of the Gelangensbestätigung (certificate of entry) which had been introduced effective January 1 2012 to simplify documentary evidence on intra-Community supplies and creating great confusion among taxpayers throughout Europe.

Legal framework

According to article 131 EC VAT Directive member states shall define the conditions for the application of among others the VAT exemption for intra-Community supplies (article 138 paragraph 1 EC VAT Directive) for the purposes of ensuring the correct and straightforward application of that VAT exemption and of preventing any possible evasion, avoidance or abuse. There have always been different views by the single member states on the appropriate type of documentary evidence that would meet those goals.

Historically, there had been quite detailed rules in place, the meeting of which had always been closely and almost pedantically watched by German tax authorities. Nonetheless, the VAT guideline themselves showed some surprising flexibility concerning the documentary evidence as such: waybills such as haulage contractor certificates had been accepted, even, under certain circumstance, confirmation by the customer that the goods had arrived in the member state of destination.

This does not mean that documentary evidence had never been put into the spotlight: in fact there had been numerous court cases dealing with details of the documentary evidence, for example the acceptability and filling of a CMR. This discussion had been obviously fed by the fact that the documentary evidence had historically been viewed as a formal precondition for the VAT exemption. One would have hoped that this discussion was ended with the judgment of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in case Collée (C-146/05) in which the ECJ confirmed that an exemption from VAT is to be allowed if the substantive requirements are satisfied, even if the taxpayer had failed to comply with some of the formal requirements. As a matter of fact the reaction by the German Federal Ministry of Finance did not veer towards that direction. On the contrary, a respective circular published on January 6 2009 signified a tightening of the tax authorities' practice bearing little relation to commercial needs likewise the new certificate of entry. On May 5 2010 another circular followed, in which the tax authorities partly took back the tightening because of recent court decisions and against their opinion held in the circular in January 2009.

In a nutshell, under the former regulations within the ordinance regulating VAT – (Umsatzsteuer-Durchführungsverordnung (UStDV)) – evidence was possible to be provided by different means depending on the factual circumstances. Besides a copy of the VAT invoice, documentation was required proving the factual cross-border movement of the goods which was to be structured in different ways depending on a transport or dispatch scenario to apply: under a transport scenario the supplier or the customer would typically use their own means of transport whereas a haulage contractor would arrange for the transport under a dispatch scenario.

In case of a transport situation evidence was to be provided by a commercial document proving the destination of the goods (for example a delivery note) plus either a confirmation of receipt issued by the customer or, where the customer picked up the goods, a written acknowledgement by the customer proving his intention to have the goods transported to another member state. In case of a dispatch a document was required such as a waybill, a consignment note or a postal receipt or otherwise a (duly signed) haulage contractor certificate comprising some key data such as the name and address of the issuer, the date of issuance, the name and address of the supplier, the commercial description and quantity of the goods, the place and date of the intra-Community supply, the recipient and the good's place of destination in the other member state and a confirmation by the issuer that there is an audit track to such data on basis of business records archived within the EC.

Recent development

On November 25 2011, the Bundesrat, Germany's federal council, approved far-reaching changes to the UStDV concerning the documentary evidence for intra-Community supplies. It should be noted that also the rules on documentary evidence for exports were amended under those legal changes, which are however not subject to this review. As far as intra-Community trade is concerned, the documents suitable for evidence have been thoroughly revised. Basically, the only permitted evidence remaining is the new certificate of entry which is applicable for both transport and dispatch scenarios. Despite not being published in the Federal Gazette before December 6 2011, the new rules were enforced already by January 1 2012 leaving limited time for businesses to change their respective processes. To face difficulties resulting from the short-dated enforcement of the new rules, the Federal ministry introduced a transitional regime on December 9 2011 by way of ministerial decree allowing application of the former regulations on documentary evidence on an interim basis.

Also, to meet business concerns and to reach consensus on the new documentation requirements, the federal ministry presented a draft version of a decree outlining the details on the new certificate of entry in the beginning of December 2011. A revised version of this draft decree considering the objection and ideas of business organisations was presented in March 2012. Furthermore, in response to the massive concerns brought forward by business organisations the transitional regime had been extended twice: first until the end of June 2012 and lately, on June 1 2012, until another amendment of the provisions in the UStDV dealing with documentary evidence for intra-Community supplies comes into force. This is not expected to happen before autumn/winter 2012/2013.

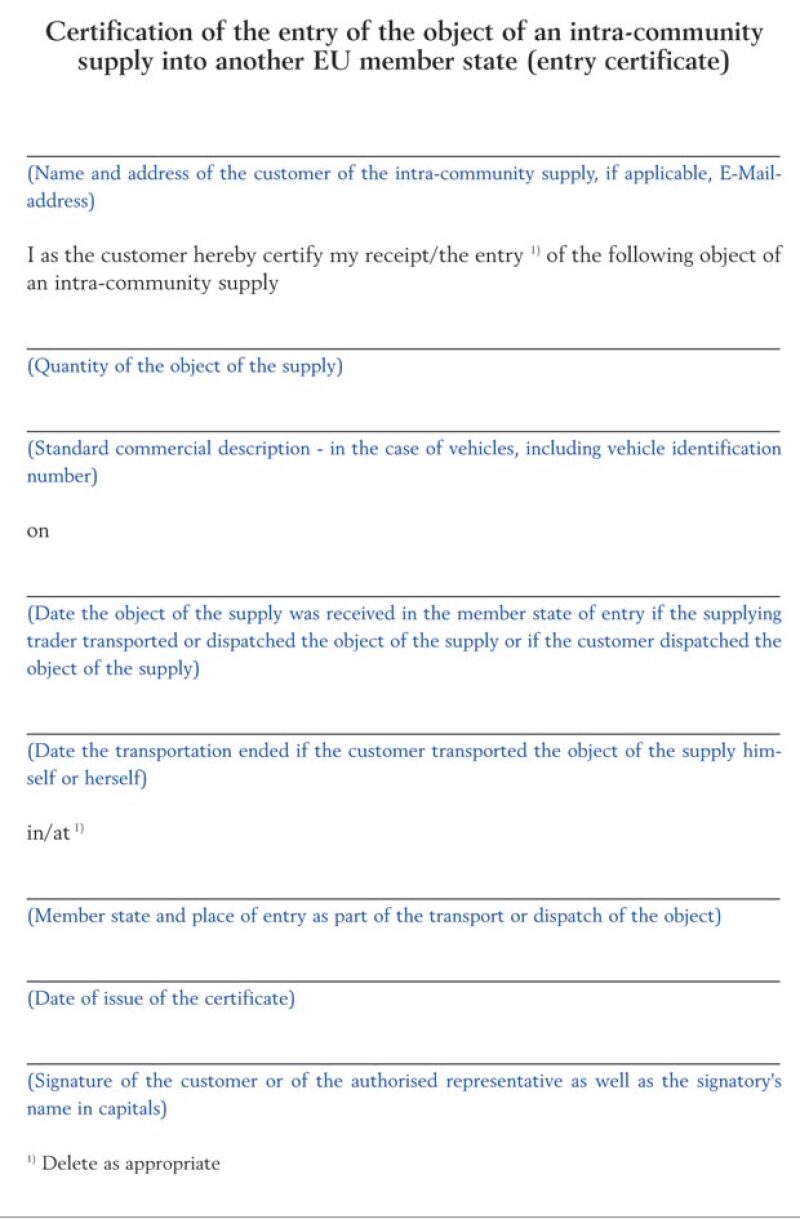

The certificate of entry

The new certificate of entry was designed to simplify and facilitate necessary documentation for intra-Community trade and to enhance controls by the tax administration. As often, black sheep were negatively impacting the flock: the former design of document proof, as the authorities claimed, led to difficulties in proving that goods had indeed been shipped out of country. In multiple cases the documentation presented by taxpayers was not positively evidencing if, when and where a distinct good was transported. Coming from there the introduction of a unique format of documentary evidence, the certificate of entry, only appears to be a logical conclusion. Where, this was the idea, the receipt is confirmed by that party in turn accounting for the intra-Community acquisition in the country of destination, a more solid audit track is created helping to avoid the sprouting of missing trader schemes which have led to billions of euros tax damage in the past.

Now, how is the certificate of entry to be structured? Does the new certificate of entry indeed lead to a simplification for businesses? According to the new rules, the certificate of entry needs to contain the following information:

Full name and address of the recipient;

Amount and customary description of the goods supplied;

Transport by the supplier and/or dispatch: place and date of receipt in the member state of destination;

Transport by the customer: destination in another member state and date the transport ended;

Vehicle identification number in case of supplies of new vehicles under article 2 paragraph 2 lit. b) EC VAT Directive;

Issuance date; and

Signature by the recipient.

Disarmingly, the German authorities tried to deal with upcoming concerns resulting from this German stand-alone solution on document proof by adding forms for the entry certificate in not only German, but also in English and French.

Details and major concerns

The changes to the UStDV in terms of document proof are manifold and, this should be acknowledged, not entirely to be demonised. Also, a vast number of the concerns originally brought forward against the new certificate of entry have been considered by the federal ministry in their latest draft of a decree outlining the consequences of the introduction of the new documentation method. Indeed the concept of using a sort of confirmation of receipt as a standard proof serves as a straightforward way of avoiding evasion, avoidance or abuse by establishing a solid audit track to the recipient of the goods in the member state of destination. Of course combating fraud is a goal which is commonly shared by taxpayers and consultants. Anyhow, it seems doubtful if this goal could be reached by simply introducing a new format for the documentary evidence. Fraudsters will likely be the first to react on the new documentation requirements and to amend their processes as keeping an eye on formal requirements is essential to their business scheme. For the vast majority of faithfully acting taxpayers, however, the certificate of entry will create an extensive additional burden and cost resulting from a necessary redefinition of their processes and getting the certificates collected, not to talk about the extensive VAT risks in case of non-compliance with the new rules, they are facing. Especially for multinational companies with operations (and VAT registrations) throughout Europe, the new certificate of entry appears to be extraordinary burdensome considering that it is preventing them from defining harmonised processes.

So, what are the major concerns about the certificate of entry? Obviously, the certificate of entry may serve as an easy solution concerning the documentary evidence where a straight forward intra-Community supply to a distinct customer is executed. Where the customer issues a respective certificate of entry, this would ease the process and clearly avoid discussion about the correctness and/or completeness of some documentation received from the haulage contractor. The certificate of entry is a national solo-attempt by the German authorities, whatsoever. As the concept is not known in the countries of destination, one may well end up in situations where the customer is refusing to sign a certificate in a language he does not understand. Even the English and French versions of the certificate of entry designed by the German authorities will not help to entirely solve this issue taking into account that they seem quite complex and not easy to understand without some topical background knowledge. Also, there is no legal claim for the supplier to get such certificate from his customer, unless this is expressively agreed between the parties (which may cause need to amend standard business conditions). Where the certificate of entry is the only possible way to provide proof, this does bring the supplier in a troublesome situation which is true even more considering that a protection of good faith does only apply where the prescribed evidence is fully met.

Especially for chain transactions the certificate of entry does not appear to be the best solution for providing documentary evidence, especially when thinking about its exclusivity on basis of the current wording of the UStDV. Where the certificate of entry requires the recipient of the intra-Community supply to have the receipt in the member state of destination confirmed, this does not generally work out for supply chains as the recipient is regularly not in a position to provide and confirm this data, but his customer or the one at the end of the chain is. Consequently, the revised draft decree allows to have the certificate of entry replaced by a dispatch voucher (using the German term Versendungsbeleg) in dispatch scenarios or where a third party physically receives the merchandise in the member state of destination. This dispatch voucher shall comprise the data foreseen for the certificate of entry such as a confirmation of receipt by the recipient, which could, as the draft decree stipulates, for example be a fully filled CMR carrying in particular a signature in box 24. This would however contradict the recent jurisdiction of the German Federal Court of Finance (BFH) which recently confirmed once again that a completion of box 24 is not a condition for documentary evidence (BFH judgment dated May 4 2011, XI R 10/09). Unfortunately, the authorities have not yet provided a sample standard voucher for VAT purposes that could be used in particular by shipping traders in practice.

The revised draft decree further provides certain easements (with some questions on the detailing of these easements still to be clarified – we have refrained from picking up all those issues in detail) on the provision of the certificate of entry in practice. The certificate may be provided by using the official forms but also by other documentation comprising the required data. This data does not necessarily have to be included in one single document but may be retrievable from multiple documents which then, together, qualify as a certificate of entry (for example combination of invoice, delivery note and confirmation of receipt). It is also not necessary to issue a certificate of entry for each and every single supply. Multiple supplies to one particular recipient may be covered by one collective document combining supplies executed within a month or a quarter at most. In dispatch scenarios the entry does not necessarily need to be attested to the supplier. It is, rather, sufficient if the receipt is attested to and archived with, for example, the haulage contractor, provided that the haulage contractor is ready to make available such documentation to the taxpayer upon explicit request (when for example under audit). Where a courier is in charge of dispatches, the revised draft decree for the sake of simplicity, allows proof by written order confirmation comprising certain details about the parcel such as a protocol of receipt of goods (also electronically by for example a tracking and tracing protocol) and a payment confirmation. In case of dispatch by regular mail a postal receipt suffices as long as a connection between a distinct supply and the postal receipt is visible. Further, an electronic issuance of the certificate of entry is also permitted, if the beginning of the transmission in the customer's sphere can be proven.

Other questions are left open still: the draft decree states that the certificate (at least when provided on paper) needs to be signed by the recipient (using the German term Abnehmer), the signature of which may be replaced by those of a person being authorised to represent this recipient. The draft decree further outlines that in doubtful cases proper authorisation needs to be proven by the taxpayer. This is obviously a regulation which is likely to cause big trouble in practice. Where an auditor enjoys hiding behind formal requirements, he may tentatively interpret those doubtful cases widely and ask for evidence of authorisation of the signatory. In most of the cases providing evidence will literally be impossible for the taxpayer, not having detailed knowledge about the internal processes of his customers at that time. The authorities tried to help here by expressly allowing proof of authorisation on the basis of the supply contract or purchase order not requiring a specific PoA for every single case. This is not really a solution whatsoever and seems to be out of touch with reality: nowadays business goods are not regularly received by the same person that has signed the supply contract or issued the purchase order. Consequently proof is not realistically going to be provided on basis of such documents. As a result, especially in bulk business, this would carry bureaucracy to the extreme as one would have to eventually hold proof for every warehouseman being authorised to receive goods and sign certificates of receipt on behalf of the recipient, even then not being absolutely sure if this is going to satisfy an auditor. Also, requiring proof of authorisation appears in general to be in line with neither the wording of the UStDV nor the respective jurisdiction of the BFH which expressively confirmed that an authorisation of receipt is not a requirement for the VAT exemption as such (BFH judgment dated May 12 2009, V R 65/06) and may only be considered in context to the onus of proof under procedural law. Needless to say that such regulation urgently requires revision.

What appears to be even more confusing is the systematic approach. As already mentioned before, based on the ECJ judgment in case Collée (also confirmed by judgment of the German Federal Court of Finance, BFH) the documentary evidence may no longer be treated as a substantive requirement for the VAT exemption. The rules set out in the UStDV may therefore express the German tax authorities' viewpoint legally on when and how proof is ideally to be made. This does not mean, however, that not fulfilling those requirements may automatically lead to a denial of the VAT exemption for intra-Community supplies. Following the ECJ, as far as an intra-Community supply actually took place, the VAT exemption does apply even where a certificate of entry cannot be presented. This does not go well with the concept of having one single type of documentation implemented as a standard proof for intra-community trade. The authorities' efforts to combine the cited ECJ jurisdiction with the definition of a standard rule for providing documentary evidence were consequently heavily criticised in Germany, saying this was a senseless attempt to square the circle.

The revised draft of the ministry's decree picks up these concerns and generally acknowledges that the VAT exemption is to be applied as long as an intra-community supply is undoubtedly executed. Nonetheless, the draft decree still carries some weaknesses in form and content. The draft decree stipulates that the receipt of a certificate of entry is a mandatory requirement for the VAT exemption and provides specific simplification rules only for some transactions (such as chain transactions, shipment via courier or postal service) where proof can be made by other means provided amongst others that the intra-community supply is evident and easy to verify on basis of those alternative documents. This bridging of the ECJ approach and the need for uniform means of proof leads to an unfortunate draft degree of uncertainty taxpayers have to deal with. Based on the draft decree, it remains absolutely unclear how a tax auditor is going to deal with the certificate of entry in future, which factually forces the taxpayer to ultimately comply with the new regulation as far as possible and to amend his processes, even though the ECJ says different. The new certificate of entry carries prima facie evidence that the goods in question have left Germany for another member state and will only be rejected as proper evidence where well-founded grounds can be brought forward. Also German tax authorities in particular tended to be pretty formalistic in the past, often not willing to deviate from the standard routines on documentary evidence and providing a tight interpretation of these despite the mentioned case law. This is why taxpayers are well advised to follow the new (revised) rules as far as possible.

Outlook

It does not seem that the tax authorities and legislative body are willing to totally refrain from the concept of the certificate of entry, but may allow other forms of evidence of transport, as well. Anyhow, they seem to acknowledge that the revised version of the UStDV has nothing in common with the interpretation of the rules on documentary evidence laid down in the draft decree, not to talk about an evident contradiction of the UStDV to the VAT Directive and ECJ principles which is why the federal ministry of Finance, browbeaten by business organisations, has announced to have the UStDV once again recast. Now it's a matter of wait-and-see if the authorities will finally manage to square the circle and to achieve what the new regulation was originally meant for: simplification and facilitation on one hand and combating fraud on the other.

Jens Müller-Lee |

||

|

|

PwC Tel: +49 711 25034 1101 Email: jens.mueller-lee@de.pwc.com Jens is a director and head of the VAT department of PwC Stuttgart. He specialises in German and European VAT with 12 years of professional experience in advising domestic and multinational companies in national and international VAT affairs. He is a lawyer and certified tax adviser studying law at the University of Bochum. He rejoined PwC in 2011 after working in the tax department of a US multinational for two years. |

Thomas Runge |

||

|

|

PwC Tel: +49 711 25034 3232 Email: thomas.runge@de.pwc.com Thomas is a senior manager in the VAT department of PwC in Stuttgart. He advises national and international companies in all areas of German tax and has specialised in VAT since 2002. He has studied economics at the University of Tübingen and joined the tax department of PwC in 1995, qualifying as a certified tax adviser in 1999. |