The media and entertainment landscape is changing rapidly with the development and adoption of new technologies, continuing vertical integration and the advent of new business models. The corresponding supply chains and their transfer pricing implications are evolving as well. This article provides an overview of the main steps in the media supply chain, discussing their primary transfer pricing implications.

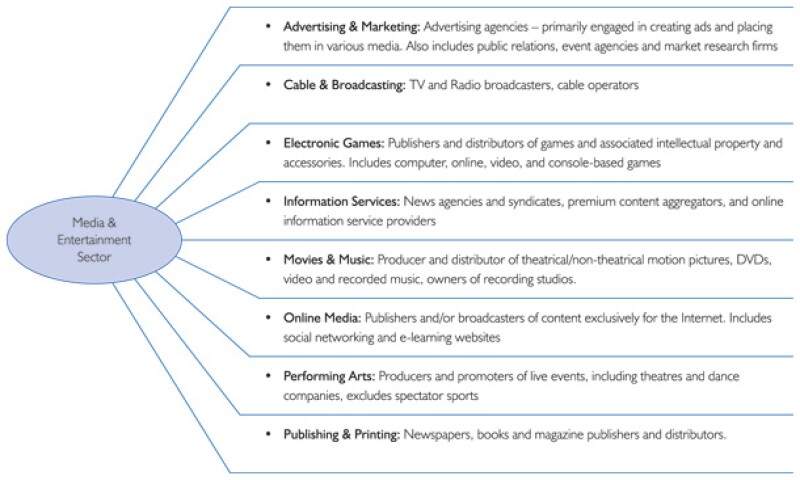

The media and entertainment sector consists of broad and diverse segments such as advertising and marketing, electronic games, information services, performing arts, and publishing and printing, each of which warrants individual analysis, as shown in Figure 1. While we will point out parallels with these industries throughout our discussion, our main focus will be the traditional media and entertainment industry consisting of the creation and exploitation of movies and other audio-visual content. Even within this simplified view of the media and entertainment industry, the complexity of the supply chain is such that identifying, characterising, and pricing intercompany transactions at each stage requires a deep understanding of the industry.

Figure 1 |

|

Overview of media supply chain

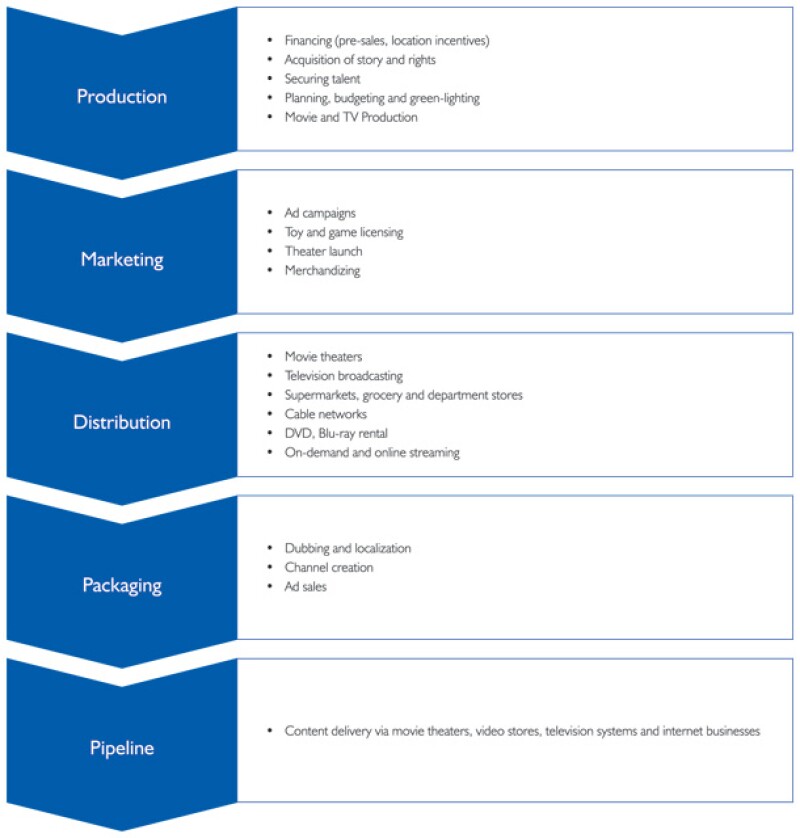

Many of the larger entertainment companies are part of diverse publicly owned companies that have operations ranging from movies to theme parks. Each entertainment company can be classified into one of the following categories: content creator, distributor, packager, or pipeline. (See Figure 3) Content creation or production companies produce movies, television shows, music, or combinations of such products. Distributors enable the public to access movies, television shows, and music through various channels including theaters, television stations, and retail stores. Packagers, usually television networks or stations, organise and schedule what consumers see and hear. Pipeline companies operate movie theaters, video stores, television systems, and internet businesses to physically deliver entertainment to consumers.

The largest entertainment companies typically straddle more than one category and operate multiple businesses. Thus, these companies are better positioned to utilise multiple means of marketing to promote their products and attractions. The larger, more established companies enjoy other advantages as well: larger companies in the filmed entertainment industry, for instance, have the ability to diversify their risk by developing a variety of projects and establishing stronger relationships with theater owners and TV networks. Larger companies also benefit from increased brand-name recognition, management experience, relationships with creative talent, and product distribution capabilities. The above factors contribute to the six largest film distributors making up 80% of US domestic box office revenues.

Figure 2 shows the scope of diversification and vertical integration of the largest companies in the industry, while Figure 3 illustrates the main steps of the media and entertainment supply chain.

Figure 2: Diversified operations & assets of major media and entertainment companies |

||||||||

Company: |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

Basic cable Network(s) |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

Bill boards/Posters |

• |

• |

||||||

Book Publishing |

• |

• |

• |

• |

||||

Broadcast TV Network(s) |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|||

Broadcast TV Station(s) |

• |

• |

• |

• |

||||

Film Production/Library |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

Internet/Broadband Sites |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Magazines/Newspapers |

• |

• |

• |

|||||

Merchandising |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

Premium Cable Network(s) |

• |

• |

• |

|||||

Radio Stations/Networks |

• |

• |

||||||

Recorded Music label(s) |

• |

• |

||||||

Theme Parks/Resorts |

• |

• |

||||||

TV Production/Library |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

?Note: some relatively minor operations may be excluded. Includes significant equity interests in joint ventures or other companies. Source: S&P Capital IQ Equity Research |

||||||||

Figure 3 |

|

Production and marketing

Production companies create content by producing movies, television shows, music, or combinations of such products. Proprietary content, such as movies or TV programming, is the intangible asset at the foundation of the media and entertainment industry.

The film production process begins well in advance of shooting the first scenes of a movie, at the preproduction phase. First, the rights to a story must be acquired, the screen play written, the necessary talent secured, and the financing arranged. Once these pieces are in place, together with detailed cost and revenue projections, the movie may be approved for production, or "green-lighted".

Production, also known as principal photography, is the actual shooting and recording of content. This is what most people imagine when they think of a film being made – actors on sets, cameras rolling, sound recording, and lighting. In large feature films, the production phase marks the point at which it is no longer financially viable to cancel the project.

The post-production process encompasses all the steps needed to go from production to a final master copy of a film, and may include adding special effects and sound track, editing, colour and exposure correction, processing and printing the film, or recording on digital media as theaters are increasingly able to project films digitally.

In addition to creating the content, the major studios also run large-scale publicity and advertising campaigns to create awareness and interest among the targeted consumer group. Such campaigns are critical not only for a film's success in theaters, but also for driving future home video, licensing, and advertising revenues. The major studios carefully plan when, where, and how the movie will be released, starting with the day it goes to production, developing the two in tandem. The campaigns typically include television and cable ad spots and teasers in the coming attraction reels, and it is not unusual for studios to spend up to $50 million in prerelease advertising on a single movie. In addition, studios can enter into promotional tie-in arrangements with fast-food restaurants, toy companies, and other retailers who provide additional advertising for related characters, toys, and video games.

The leading media and entertainment companies compile and maintain extensive libraries of proprietary content that continues to generate revenue for many years after the original release date.

Distribution

Distributors enable the public to access movies, television shows, and music through various channels including theaters, television stations, and retail stores. The US is the lead exporter of TV productions in the world. In the European Union, for instance, more than 60% of broadcast TV content was produced in the US. Distributors alter much of this content before it is broadcast abroad to appeal to foreign audiences. Alterations are often done through dubbing and subtitles and can drastically change the original production to reflect local culture and jokes. These TV programmes are often considered coproduced by the original US producer and by the production company that adapts the content to be country-specific. As a result, revenue can be difficult to track, because it is accounted for by international distribution divisions and coproduction companies abroad. IBISWorld estimates that exports generated about 13.5% of the 2012 industry revenue.

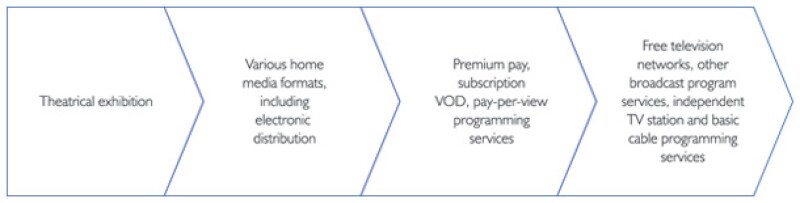

The major studios derive motion picture revenues from four basic distribution sources, set forth in general chronology of exploitation in Figure 4.

Figure 4 |

|

For any given film, box office receipts and home video sales (both domestic and international) account for an overwhelming portion of gross revenues. However, other channels, such as TV licensing and pay-per-view, as well as emerging platforms such as video-on-demand (VOD) and Internet downloads, also contribute a meaningful portion of a film's total ultimate earnings over its life span. Figure 5 summarises the industry's primary box office and home video sources of revenue.

Figure 5 |

|||

Description |

Revenue Driver Formula |

||

Box Office |

Admission |

Tickets: a piece of paper used for admission into theatres |

(Number of tickets sold) * (Average ticket price) * (Revenue share percentage) |

Advertising |

Online / Mobile: promotional campaign through internet or messages |

[(Total ad views) * (Average ad CPM)] or [(Total ad clicks) * (Average click through price)] |

|

On Screen: broadcasts amid movies in theatres and television |

(Number of broadcasts) * (Average ad price) |

||

Home Video |

Content |

DVD, Blu-ray, and Cassette media storage formats: sale and rental |

[(Number sold) * (Average sales price) * (Revenue share percentage)] + [(Number rented) * (Average sales price) * (Revenue share percentage)] |

Online/ Mobile downloads: transfer of audio/ video data from a host or server to a device |

[(License fee) + (Number of downloads) * (Average download price) * (Revenue share percentage)] |

||

Advertising |

Online / Mobile: promotional campaign through internet or messages |

[(Total ad views) * (Average ad CPM)] or [(Total ad clicks) * (Average click through price)] |

|

In-video: broadcasts amid movies played through discs/ cassettes |

(Number of views) * (Average ad price) |

||

Consumer Products Licensing and Promotions |

Earned by providing production intellectual property to third parties through consumer products licensing, game distribution, and promotions |

(Licensed goods revenue)*(Royalty rate percentage) |

|

For movies exhibited in theaters, box office receipts are the most frequently published measure of success. However, those numbers do not tell the whole story and may be misleading without a more detailed analysis of the supply chain. First, movie theaters retain approximately 50% of the money that consumers spend at the domestic box office, passing the rest on to the distributor. The distributor, in turn, may deduct its prints advertising expenses, as well as a distribution fee of 15% to 30% of the total gross receipts for a movie. As a result, the studio receives only a portion of the revenue.

Take, for example, "Casino Royale" which was released in November 2006 and had a production budget of approximately $150 million. The film's lifetime worldwide gross receipts were approximately 600 million.

600,000,000 |

Gross receipts |

|

- |

300,000,000 |

Retained by Theaters (50 percent of gross receipts) |

- |

43,900,000 |

Printing and advertising cost reimbursed to distributor |

- |

180,000,000 |

Distribution fee (30 percent of gross receipts) |

- |

150,000,000 |

Production budget |

- |

73,900,000 |

Profit/(Loss) |

Six years after its original release date, the film may still be in the red based on theatrical revenue alone. However, with fewer intermediaries such as movie theaters, the studios typically receive a larger share of home video revenue, and rely on this and licensing revenues to make up for this shortfall.

Packaging

Packagers, usually television networks or stations, organise and schedule what consumers see and hear. Their activities include acquiring programming, compiling audiovisual content to form a cohesive programme, and digitally transmitting television programming to broadcasters. Packagers may also engage in the provision of limited format programming, such as news, sport, or educational content.

Pipeline

Pipeline companies operate movie theaters, video stores, television systems, and internet businesses to deliver entertainment to consumers.

Although physical home video sales have been declining since 2004 (and this trend is expected to continue), new ways to access video content are predicted to continue to compensate for this loss and lead to an overall steady combined market growth. Online video revenues have been increasing as a result of subscription-based services, and the VOD segment has improved thanks to more available titles, promotion campaigns, and day-and-date releases (which are simultaneous with the physical home video release). Electronic sell-through has also been increasing thanks to iTunes and similar services, though concerns exist over losing files and the ability to watch on multiple devices.

Digital media are projected to overtake the more traditional home video mediums within the next 10 years, digital downloads and VOD replacing physical home video products, and technology firms becoming increasingly intertwined with the media industry. The distinction between media and technology companies, between content and software, may become obsolete.

Transfer pricing implications

The most common intercompany transactions within the media and entertainment industry are the use of intangible property, the provision of services, and distribution. In the following sections we will address the industry-specific aspects of these transactions for transfer pricing practitioners at each major step of the supply chain: production, marketing, and distribution. The packaging function is, in practice, often integrated into the distribution process and is discussed together with distribution activities. Further transfer pricing implications for the pipeline are considered in "Transfer pricing opportunities and pitfalls as a result of telecom convergence", also in this issue.

Production

IP and licensing

For the largest media companies, their global intangible property – content – is typically owned by a US parent and entrepreneur. Production for many of the companies is based in Los Angeles or similar locations, and cannot be easily moved. Furthermore, companies value the well developed and enforceable rules for patent and copyright protection in the US, relative to other jurisdictions.

A typical structure in the media industry is for a US affiliate to own the global IP and either license the foreign rights to this IP to its distribution affiliates abroad, or engage the marketing and sales services of these affiliates. Under the licensing scenario, several variations can be observed. The affiliates may license the content (movie, show), which is then shown in local movie theaters, or used to create a local channel. Alternatively, affiliates may license the distribution rights to a complete channel, as well as the rights to sell advertising on this channel. In both cases, the media companies frequently engage in similar transactions with unrelated distributors creating a large pool of potentially comparable market transactions that should be carefully evaluated for comparability with the intercompany licensing arrangements.

Under US Treas. Reg. §1.482-4(c), the comparable uncontrolled transaction (CUT) method evaluates the arm's length nature of an intercompany charge by reference to comparable uncontrolled transactions. If an uncontrolled transaction involves the transfer of the same intangible under the same (or substantially the same) circumstances as the controlled transaction, this method will ordinarily provide the most reliable measure of an arm's length charge. Circumstances are considered substantially the same if only minor, quantifiable differences exist for which appropriate adjustments can be made. Factors that are particularly relevant in determining comparability under the CUT method (besides the property itself) include contractual terms and economic conditions. For the intangible involved in the uncontrolled transaction to be considered comparable to the controlled intangible, both must have a similar profit potential, and be used in connection with similar products or processes within the same general industry or market. Other factors to be considered are the terms of the transfer, the stage of development, rights to receive updates, revisions, or modifications, uniqueness of the property, duration of the license, economic and product liability risks, existence of collateral transactions, and functions performed by the transferor and transferee.

In the media industry, each intercompany and third-party licensing transaction is often individually negotiated considering a number of industry-specific factors. These may include viewer ratings, the star of the show, type of content (movie, series, documentary), whether the license includes rights to show on free or pay TV, whether the content has local or global appeal, the number of allowed reruns, as well as the date of the original release and age of the content. Furthermore, an evaluation of the profit potential of a particular movie or show should consider all potential sources of revenue, including theatrical, home video, and advertising over the term of the license or the life of the content.

Production services

The tax and transfer pricing implications of film production are complicated, because it is common practice in the industry to set up separate wholly or partially owned production companies for each film. The production company carries out all related activities as a service provider on behalf of the IP owner. Because many countries provide substantial tax and other incentives to attract the jobs and investment that come with film production, it is not uncommon for the production company to be located outside the US, giving rise to cross-border intercompany transactions. For example, the Canadian federal government provides a subsidy – the film production services tax credit – to qualifying foreign producers. In addition, British Columbia offers an 18% rebate on labor from that province. Finally, there is a 20% break in digital effects, if they are done in Canada. Other countries with specialised incentives for the movie industry include Germany, New Zealand, and the UK.

The comparable profits method is frequently applied to analyse the cross-border intercompany provision of production services. However, due to the specialised nature of the activities and the challenging economic environment for the media industry in recent years, closely comparable companies are difficult, if not impossible, to identify. Most independent production companies own significant intangible assets both in the form of extensive content libraries and human capital. In addition, many independent studios are either undergoing financial restructuring or business consolidation. As a result, companies in the industry are often forced to rely on loosely comparable general service providers for transfer pricing purposes when analysing market returns for production services.

Marketing and distribution

Typical services include marketing and advertising, technical support, satellite and broadcasting, and equipment rental services. Distribution commonly involves the sale of content and advertising space. With most IP typically owned by the US parent, the most common challenge for the industry is to plan and analyse the appropriate amount of profit to be left with the non-US affiliates of the group, which are often regarded as either (1) distributors, paying royalties to the US entrepreneur and IP owner, or (2) limited-risk service providers. Furthermore, the question of whether local market insight and know-how constitutes valuable intangible property remains to be answered by the industry.

The functions and risks of the distribution affiliates within multinational media companies are changing with the transition from film prints and physical home video media to digital media. As digital media overtakes traditional home entertainment products, these companies will no longer need to maintain inventory of DVDs, cassettes, and Blu-ray disks to be shipped to video rental stores across the world, their country, or region. However, companies will still need to maintain relationships with their customers and gather valuable local market intelligence, as well as adapt centrally produced content before it is broadcast to appeal to local audiences. The transfer pricing implications of this shift from distribution to services activities should be carefully planned for, considering both US and non-US risks, compliance requirements, and opportunities.

Once an affiliate has been characterised as a distributor or service provider, the comparable profits method (CPM) is frequently applied to analyse the affiliates' profitability. However, due to the specialised nature of the activities and the media industry, closely comparable companies are difficult to identify.

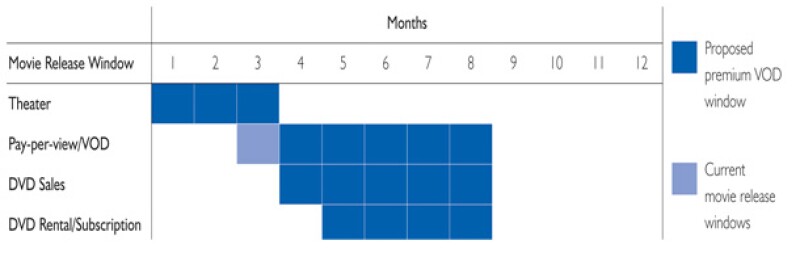

CPM analyses are further complicated because media companies frequently operate a number of affiliates in the same country, whether for operational or historic reasons, with each affiliate specialising in a different distribution channel, such as theatrical, home video, or digital. In such cases, when multiple affiliates distribute the same content through different distribution channels in the same market, the interrelated nature of the revenue streams from theaters, TV channels and home video should be considered. Aggregating the financial results of these affiliates may more accurately reflect the complete supply chain of the media industry in a country for transfer pricing testing purposes. With the major studios having already shortened or considering shortening the release windows for different distribution channels, revenues from each are becoming more interdependent, with significant overlap in timing, as shown on Figure 6.

Figure 6 |

|

Finally, data from multiple years usually must be considered when applying the CPM. Generally, three years (the tested year and the two preceding years) of data are used, unless the specific facts of the case warrant a longer period. In the media industry, content can generate revenue for many years after its original release. The American television sitcom "I Love Lucy," which was originally launched in 1951, can still be seen on TV today and purchased on DVD and Blu-ray. Longer periods of analysis are therefore often appropriate to capture the full flow of returns in the media and entertainment industry.

Other transfer pricing considerations

Multistate transfer pricing

In the US, multistate transfer pricing issues can be significant for companies in the media and entertainment space. Most states offer special incentives to the film and television industry competing to attract the business and jobs from the production and distribution of films. Incentives may be in the form of tax credits, which can either be used or sold, or in the form of direct reimbursements of production costs. For example, beginning in February 2008, the Michigan film production credit provides a refundable, assignable tax credit of up to 42% of the amount of a production company's expenditures (depending on type) that are incurred in producing a film or other media entertainment project in Michigan. In Arkansas, the Digital Product and Motion Picture Industry Development Act of 2009 created incentives for digital product and motion picture productions that include a 15% rebate on all qualified production expenditures made in Arkansas.

These incentives add further complexity to diversified media and entertainment companies' operations in most states. Transfer pricing is an issue in states that require separate filing for related, multistate corporations. Currently more than half the states that impose a corporate income tax require separate filing. With many states having adopted the Treas. Reg. §482 statutory language, multistate transfer pricing considerations, in the context of both content production and distribution, are of significant concern for the industry.

California, Hollywood's home state, has increased its emphasis on related-party audits involving foreign affiliates, and its auditors have been aided by various legislative and administrative changes. States such as California are now imposing penalties for failure to provide documentation supporting the transfer price reported on a return. In California, each taxpayer filing under the unitary method (including those making a water's-edge election) must maintain and make available on request books, papers, or other data affecting the calculation of a controlled taxpayer's true California taxable income. A taxpayer's failure to timely comply with an IRS request for documentation may result in significant financial exposure, according to Treas. Reg. §1.6662-6. California has adopted the relevant federal transfer pricing penalty provisions of Internal Revenue Code §6662, making the failure to comply with a Franchise Tax Board request for documentation likely to result in similar penalties. Therefore, media and entertainment companies should assess the need for more comprehensive documentation of their multistate intercompany transactions and policies.

Joint ventures

Major studios, which are primarily headquartered in the US, are expected to increasingly invest in developing markets to capitalise on audience growth in those countries. US production studios dominate the production and distribution of movies, and there are few entities outside the US that have similar production capabilities in terms of infrastructure, production financing, marketing, and distribution reach. However, the disposable income levels of consumers from rapidly developing, newly industrialised nations like Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC nations) are rising quickly and expected to support industry revenue expansion of 1.5% in 2013. In addition, media companies are increasingly looking to use outside resources to expand their digital presence and the variety of content to offer as consumers' options expand. These factors contribute to the frequency of joint ventures in the media industry that can have transfer pricing implications.

China, for example, has until recently posed a myriad challenges for US filmed entertainment companies. Among such hurdles were censorship of content, protectionism, stringent media ownership caps and regulations for foreign-controlled entities, lack of legal and political transparency, cultural differences, bureaucracy, and piracy.

Now it appears that the Chinese market is becoming more welcoming to foreign studios. For instance, under its previous quota system, China allowed only 20 foreign film releases in its market each year, primarily outside of an imposed blackout period that coincided with popular movie-going seasons (such as, the Chinese New Year). However, following an announcement in February 2012 by Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping and his US counterpart Joe Biden, this limit was raised to 34 for films made in 3D or IMAX formats. China has also increased the share of earnings for foreign studios from about 13%–17% to 25% of the movies' box office sales in China.

Following these recent developments aimed at cross-country collaboration, the market has witnessed a flurry of deals in which US studios are entering into joint ventures with Chinese studios. For transfer pricing purposes in China, an enterprise and another enterprise, organisation, or individual are considered "related parties" if they have any of the following relationships, among others:

A party directly or indirectly owns 25% or more of the shares of the other party, or vice versa;

The party's production and business operations depend on the other party's patent, proprietary technology, or other licensing, etc.;

The provision and receipt of services of the party are controlled by the other party.

As a result of this relatively stringent definition of a related party for Chinese transfer pricing purposes, many of the US studios' joint ventures with Chinese studios may qualify as related parties, and therefore may be required to comply with transfer pricing documentation requirements or be subject to penalties in case of an audit.

Industry-specific TP challenges

Companies in the media and entertainment space are facing unique industry specific transfer pricing challenges. Given the predominance of US IP ownership in the industry, it is important to focus on adequately planning for and documenting the profitability levels of non-US affiliates. Robust transfer pricing documentation may prove especially critical in mitigating foreign audit risk. In addition to IP transactions, particular attention should be paid to intercompany service transactions due of their specialised nature. Services such as content production, news gathering, and content localisation play a significant role and are often difficult to benchmark, requiring deep industry expertise to identify adequate comparables. Furthermore, the media and entertainment supply chain is continuously evolving and integrating with adjacent industries, as technology companies are successfully producing content and traditional media companies are acquiring hi-tech distribution channels. These changes further underscore the importance of reviewing and reconsidering transfer pricing policies and documentation on a regular basis.

Biography |

||

|

|

Kristine Riisberg Principal Deloitte Tax LLP Tel: +1 212 436 7917 Email: kriisberg@deloitte.com Kristine is a Principal in Deloitte's New York office. She has more than 15 years of transfer pricing and international tax experience with Deloitte and spent four years in Deloitte's Washington National Tax Office. Kristine has extensive experience in company financial and quantitative research analysis and industry data analysis in a wide range of industries. She has prepared economic analyses, documentation, planning, competent authority requests and cost sharing studies for clients in the following industries: media and entertainment industry, telecommunications, digital, computer software, semiconductors, publishing, oil and gas upstream and field services sectors, power generation and renewable energy, chemical industries, healthcare and medical industry, financial services, automotive and automotive suppliers, quick service restaurants, travel industries, consumer goods, and commodities industries. Kristine has with her international background and experience working in Deloitte transfer pricing teams in Copenhagen and London build up an extensive knowledge of global transfer pricing matters. Kristine is the Americas transfer pricing leader of the Technology, Media & Telecommunications industry programme. She assumes the global lead tax partner role for the World's largest container shipping conglomerate, the global lead TP role for a U.S. based Media Conglomerate and the U.S. lead TP role for the largest European headquartered Consumer and Industrial Goods Conglomerate. Kristine has given numerous speeches and presentations at the American Conference Institute, Tax Executives Institute, BNA, Atlas, Thompson Reuters, CITE, Deloitte Debriefs and Conferences on transfer pricing issues. Prior to joining Deloitte, Kristine was an international tax manager at Andersen's Copenhagen office. Before joining Andersen, Kristine worked at the European Commission in Brussels in the Cabinet of the Danish Commissioner for Energy and Nuclear Safety. Education

|

Biography |

||

|

|

Anna Soubbotina Global Transfer Pricing Services Deloitte Tax LLP Tel: +1 212 436 3952 E-mail: asoubbotina@deloitte.com Experience Anna is a senior manager in the Global Transfer Pricing service line of Deloitte Tax, New York. She has seven years of specialised cross-border and multi-state transfer pricing experience, of which she spent two years in Deloitte's Washington National Tax Office. Anna's experience includes managing projects in the following industries: consumer products, media and entertainment, energy and power generation, chemical, industrial equipment and automation, software, financial services, and healthcare. Anna has a proven track record consulting on a multitude of transfer pricing issues and the preparation of transfer pricing risk assessments under ASC 740, documentation, planning and audit defense studies, including cost allocation and services analyses, tangible and intangible property. Her focus is on intellectual property and cost-sharing projects involving the valuation of intangible assets, derivation of platform contribution payments and development of royalty rates for the use of intellectual property. Anna manages and coordinates the preparation of global transfer pricing documentation for Deloitte Tax's largest clients, covering as many as 30 jurisdictions. Throughout this process, she ensures compliance with the US transfer pricing regulations, as well as consistency with the OECD guidelines. Anna works closely with Deloitte Tax's global network of specialists to bring clients the benefit of deep local country transfer pricing expertise. Anna has designed and presented Deloitte Tax training on the following topics:

Education Anna earned her Master of Science in Finance from Imperial College London, UK and received a Bachelor of Science (Honors) in Economics from the University of St. Andrews, UK |