Multinational enterprises continue to shift portions of their value chain to global and regional platforms to achieve business efficiencies. Technology advances are enabling organisations to connect globally and "franchise" their business models to create globally integrated enterprises. Digitally driven processes and the use of data are emerging as value drivers. While traditional stakeholders, such as the C suite and board members, continue to view tax management as driving value, new stakeholders have emerged, including media, consumers, and employees. In the meantime, local governments are focused on eliminating deficits and are showing a more aggressive enforcement activity to collect taxes. Given all these changes, what are the key implications for managing global tax in the future? We will discuss the need for a flexible model that can accommodate change and the increased focus on communicating with business leaders.

All the change in today's environment has disrupted the focus of traditional global tax planning. More than ever, transfer pricing plays a central role. International tax management is no longer primarily focused on transactions or legal restructuring. Today one of the key responsibilities of tax executives is understanding the current business model and the key strategic initiatives driving the future of the company's organisation. Managing a global tax posture that is driven by the business model requires a different skill set. Effective global tax management now requires the tax executive to have a seat at the table with management and business segment leaders for two important reasons: (i) the exchange of information on what's happening in the business will help both teams move forward in a much more efficient manner; and (ii) tax executives are now first in line to provide support for the company's tax position to a variety of new stakeholders, in addition to the tax authorities.

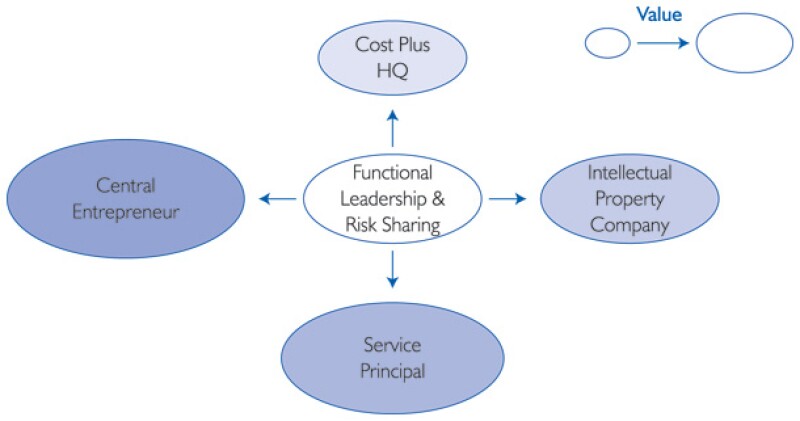

In addition to understanding the organisation's business model, tax executives must now be actively engaging in the process of Business Model Optimisation (BMO). This requires an understanding of different operating models, underlying transfer pricing methodologies and legislative direction. The chart below summarises the primary BMO alternatives, all of which are driven by distinct transfer pricing principles.

Alternative BMO models

The traditional BMO model is referred to below as a central entrepreneur (CE). The CE is an operating company that manages key functions that drive profitability, funds innovations, and manages risk. The local operating companies act as limited-risk distributors, or cost plus service providers. At the other end of the spectrum would be a centralised cost plus service provider that functions as a headquarters (HQ) providing guidance and routine management services to the local operating companies, rather than a centralised operating company that provides the strategic control and oversight of the local operating companies, as would a CE. Within the spectrum of alternatives is a pure intellectual property (IP) manager and owner (IP Company), providing the use of the IP rights to the local operating companies by means of license agreements. A more substantive BMO model than a pure IP company has emerged in recent years. We call this enhanced BMO model a Service Principal whose functions are strategic for the group, and that delivers added value services and leading practices. The Service Principal may have IP embedded in the services it provides, in which case it takes on characteristics similar to a franchise arrangement. However, the Service Principal model and the IP models can work side by side rather than being combined, as discussed below.

We will discuss how to combine these alternative BMO models to create a flexible BMO platform that accommodates the multiple fact patterns within a group, and more importantly, accommodates change.

Let's use the technology, media & telecom (TMT) industry as an illustration. The TMT industry has at least two primary areas of focus that drive BMO: TMT "content" and the TMT business model. The BMO IP models generally apply to content. These models can be complex due to profit sharing, joint ventures, and risk management. New content models are emerging to capture the value of data. This article will focus on the evolving TMT business model and how to increase value and manage change using a flexible BMO model. The flexibility concept may also apply to the "content" models within the organisation.

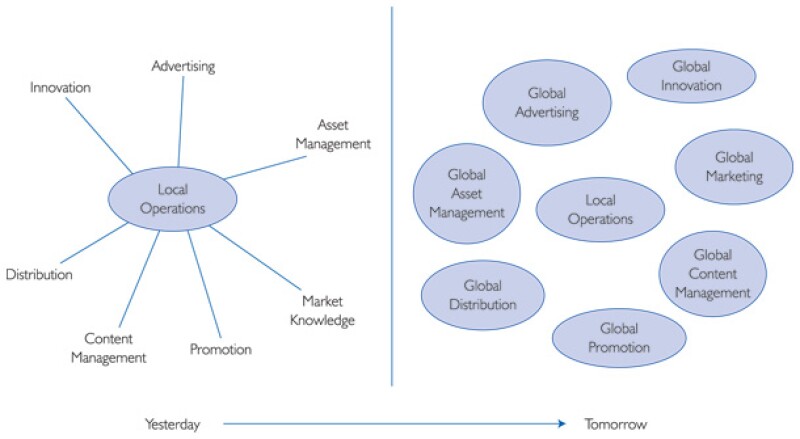

The premise of a flexible BMO platform is that, in an ideal world, significant components of the value chain would be centralised in a single, tax-efficient country where the functions and risks are managed and deployed for the benefit of the local operating companies. A common term for such a structure is a "hub". When these hubs are formed as "virtual Hubs" without regard for geographic boundaries, opportunities may be lost. These hubs have emerged as a result of value creation being driven by global or regional functions located outside the local operating company, whereas at the same time the value created in the local operating company decreases. The functions within the local operating company may be solely execution and local relationships. In fact, TMT business models are increasingly looking like a classic franchise model. This dispersion presents potential opportunity when it can be located within a BMO model, as opposed to being dispersed as in the case with a virtual hub.

Diagram 1: Alternative BMO Models |

|

Dispersion of the value chain

This dispersion may start small (purchasing, information technology) and evolve over time. Any significant movement toward regionally or globally managed functions provides an opportunity to start building a tax-efficient BMO platform. A flexible platform starts with the creation of a solid core of functionalities around a hub that can grow as new globally or regionally managed functions evolve over time. The hub platform may have geographic focus (Asian hub in Singapore and EMEA hub in Ireland, Switzerland, Netherlands, for example) and flexible platforms may integrate multiple hubs in a manner that reconciles their value add so as not to create an unbalanced transfer pricing situation.

Over time, a hub may add functionality or increase risk management. This "top down" approach creates an increased level of value at the hub. Flexible BMO platforms accommodate change for the top down approach. Failure to identify top down changes can result in lost opportunity, but also tax risk. Organisations will continue to move toward global and/or regional functionality, process standardisation, resource sharing, and centralised asset management. For example, if we examine the functionality of a BMO model created five years ago, we would expect to see an increased level of functionality.

Managing an existing BMO structure from the top down requires deeper communication with business segment leaders and the C-Suite. Management needs to understand the underlying principles of the company's operating model(s) and be aware that change creates both opportunity and risk. This is especially true in cases where physically locating the management and funding of new initiatives in the Hub can generate incremental savings for the business to reinvest. Management communication is effective only when it moves past concept and toward reality. The use of analytics and scenario analysis will clarify the message. Communication becomes more important in today's environment, because management must respond to the different stakeholders, including the media, employees, and tax inspectors.

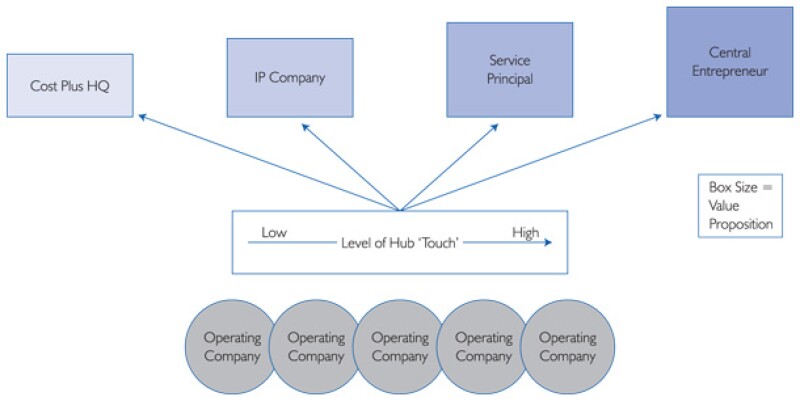

Equally important, the flexible BMO model must accommodate change from the bottom up. Bottom up change relates to the increasing level of reach within the global organisation. As more of the organisation receives the benefits of the evolution of the operating model, the expected results are increased revenues, cost reduction, or both, creating margin improvement. Over the years, the increased coverage results in more value creation outside the local operations. Keeping close communications with the hub allows the identification of bottom-up change. Including larger portions of the local operating companies within the BMO platform represents opportunity. For example, the flexible BMO platform allows some countries to participate in a CE model, while others participate in a Service Principal model or an IP Company model.

Failure to identify bottom up changes can result in added risk. As local tax authorities demand more transparency, they will likely inquire about hub activities and compare and contrast. For example, a hub created five years ago in Singapore may have included Japan in the model under a limited-risk model (Japan earns a commission under a CE model). During the Japanese tax audit, it was discovered that the hub recently began providing substantially the same level of functionality to China (which historically paid the hub for routine services). The Japanese tax authorities will likely ask for reconciliation of the two profit profiles. In fact, in Europe, the tax authorities are more frequently seeking input from other tax authorities, and are looking to manage audits on a coordinated basis. With respect to bottom up change, the difference between opportunity and risk is continual communication with hub management and business segment leaders.

It is not uncommon for many organisations to have undertaken BMO alignment focused on the CE model. However, the use of such a model has frequently not been possible in some jurisdictions, particularly in Latin America. An increasingly common situation involves a regional CE model that has evolved over the years and now may be providing all its services to a number of affiliates in countries that are not part of the original CE model transformation. In many cases, those local operating companies may not fit a limited-risk model despite receiving practically the same level of functionality and risk management commonly associated with a CE model. These restrictions may include regulatory issues, indirect tax costs, and local-country permanent establishment risk. The value added services provided by the hub do not fall within the definition of "routine services". A flexible BMO platform may allow this country to be included under a Service Principal model to reflect the value added services. The local operating company would continue under the existing IP model, or the IP could be integrated as part of the Service Principal model. If combined, the Service Principal would license (or acquire) the IP and the value of the IP would be reflected in the fee charged to the local operating company.

The Service Principal Model provides a link to allow a flexible BMO platform. The flexible BMO platform is built on a core of functionality that is accessed by the local operating companies at different levels of 'touch.' There are many factors that determine which of the BMO models apply to a particular operating company, including local-country regulatory issues.

Diagram 2: Dispersion of the Value Chain/td> |

|

Diagram 3: Flexibility to Accommodate Change |

|

Flexibility to accommodate change

As discussed earlier, the Service Principal model reflects the provision of value added services to the local operating company. It is essential to the flexible BMO platform because it can stand alone as a provider of high value services, be potentially combined with IP, and also enhanced through risk management activities. Separate transfer pricing policies can be supported for each of the BMO models and reconciled in a manner that reflects their individual value proposition. This flexibility can be applied on a country-by-country basis, as illustrated above. Criteria for moving from one BMO model to another model (Service Principal to CE, for instance) can be established based on the level of touch or other relevant factors that indicate the value the hub provides to the local operating company.

A stable platform requires transfer pricing that can be reconciled and justified to the local tax authorities. For example, a local operating company may make service payments under a Service Principal model and separately make IP payments to the IP owner, each payment supported under the appropriate transfer pricing guidance. Care must be taken that the two payments can be reconciled. Franchise agreements often provide the best support for determining the appropriate fee under the Service Principal model. When using franchise agreements as transfer pricing support, it must be recognised that these agreements generally include an IP component. In the example above, the range of franchise fees from comparable franchise agreements must be reduced to remove the IP component.

Analysing the international tax consequences of the Service Principal model requires coordination between international tax and transfer pricing practitioners to conclude that the local operating companies are being provided value added services as the primary component and the appropriate level of intellectual property. This issue receives additional attention when using franchise agreements to support the transfer price, because the fee may be calculated as a function of revenue. While justified from a transfer pricing standpoint, tax authorities' initial reaction may be to call it a royalty. Royalties may be subject to withholding tax, whereas services are generally not subject to withholding if the services are provided outside the local operating company's country (other than in many Latin American countries). For US multinationals, the distinction between services and royalties has a direct bearing on the tax efficiency of the hub. Management needs to be aware of the need to support the provision of services and the value provided to the local operating company.

In most cases, in real life instead of in an ideal world, operating models rely not only on resources employed by the hub, but also on resources employed by affiliates in other geographies. The hub typically reimburses these shared service centre operations for such activities under a cost-plus service fee model. It is important to determine the activities and management of such individuals to avoid creating a permanent establishment for the hub in the country where the contracted work is performed. In addition, indirect tax may be levied on cross-border service fees. These taxes may influence the choice of operating models, because in some countries the indirect taxes may create significant additional costs if not fully recoverable.

Despite the complexity, change can bring opportunity to those who have a flexible BMO platform and good lines of communication within the organisation. So, where do you start? Does your existing hub need a refresher? Is your organisation just beginning to globalise or regionalise, either virtually or physically, portions of its value chain? In either case, it starts with analytics to understand margins and cost pools; engaging with management to identify global or regional initiatives that create value; and performing an analysis to develop a high-level understanding of the impact of alternative BMO models. Executing these tasks will provide what is needed to build a flexible BMO platform, better after-tax decision-making, and sustainable tax savings.

Biography |

||

|

|

Daniel Munger International Tax Partner Deloitte Tax LLP Tel: +1 312 486 9830 Email: dmunger@deloitte.com Mr. Munger has more than 30 years of tax and accounting experience delivering global tax and treasury strategies to Fortune 500 multinational businesses. His focus on strategic international tax consulting for multinational organisations includes U.S. and local county tax planning for mergers and acquisitions, supply chain transformation, intellectual property alignment, service principal companies, foreign tax credit planning, treasury strategies, repatriation, cash mobilisation strategies, and strategic transfer pricing. Mr. Munger is the Global leader of the International Strategic Tax Review (ISTR) practice. This global practice within Deloitte Tax delivers holistic strategic planning to ensure long term sustainable effective tax rate reduction. In this role, Mr. Munger has assisted many U.S. and non-US multinationals in designing integrated tax and treasury strategic plans and executing multi-year strategies. The Global ISTR practice consists of a team of professionals that have developed specialised tools, models and processes that facilitate in the design and implementation of global tax and treasury strategies. Mr. Munger is also the US Market Strategy and Innovation Leader for the International Tax Practice and is focused on connecting the many diverse skill sets within Deloitte to bring value to clients. In this role, Mr. Munger looks to the challenges our clients face in developing, executing and maintaining global tax strategy in order to identify new initiatives and solutions. An example is the use of data analytics and interactive tools for strategy development and monitoring. Mr. Munger has also played a key role in various international think-tank efforts and has been a contributor to the development of innovative tax solutions to support client business strategies. Mr. Munger is a frequent lecturer on a variety of international topics and tax accounting matters with groups such as the Tax Executives Institute, MAPI and the World Trade Institute. Education Purdue University – BSIM Professional and Community Activities Member, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Member, Illinois CPA Society |

Biography |

||

|

|

Andrew Newman Partner Deloitte Tax LLP Tel: +1 312 486 9846 Email: acnewman@deloitte.com Andrew Newman is a tax partner specialising in international tax matters for multinational companies (MNCs). With more than 30 years of experience, he serves multinational clients in a variety of industries, including manufacturing, services, specialty chemicals, fast-moving consumer goods, food processing, and distribution and franchising. Mr. Newman is the Co-Global Leader of the Business Model Optimisation (BMO) service offering. In this role, Mr. Newman is heavily involved in working with MNCs in optimising their supply chains and operating models and the tax benefits that can flow from such business transformations. This has included the design and implementation of principal and intellectual property company structures for Europe and Asia. BMO focuses on creating value though business transformation. Mr. Newman has performed numerous global strategic tax reviews for MNCs to focus on reducing their worldwide effective tax rates. In addition, he has been instrumental in pioneering a new approach to managing the effective tax rate of a global company while optimising its utilisation and repatriation of offshore cash. He has successfully implemented this Global ST2EPS methodology for many U.S.-based multinational companies. In a highly regarded international survey on tax advisors, Mr. Newman recently was recognised as one of the leading international tax service professionals in the central region of the United States. The study, conducted by the International Tax Review, gathers and assesses feedback on accounting and law firm tax advisers from 2,000 in-house tax experts and chief financial officers at major companies and financial institutions throughout North America. Mr. Newman is also listed as one of the 2010 World's Leading Tax Advisor's. Mr. Newman has published several articles on international tax matters in such magasines as The Tax Executive, Investment USA, and The International Tax Management Journal. Mr. Newman is a co-author of the BNA Portfolio on the Allocation and Apportionment of Deductions. He has spoken on international tax matters to various tax groups, including The Chicago Tax Club, the Tax Executives Institute, CITE, the International Fiscal Association, and the National Chamber Foundation. Mr. Newman is a member of the International Fiscal Association, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, and the Illinois CPA Society. |

Biography |

||

| Sophie Blégent-Delapille Senior Director Deloitte Taj Tel: +33 1 40 88 72 05 Email: sblegentdelapille@taj.fr Sophie Blégent-Delapille is an international tax partner in Deloitte's Paris office (France). Sophie has over 22 years of tax experience and leads the corporate tax practice in France, which includes international tax, business tax and M&A. Sophie also leads the Deloitte EMEA International Strategic Tax Review market offering to assist multinational European groups in the alignment of their business strategies with a sustainable tax profile. She specialises in International tax, focusing on large cross border projects, including business model optimization and IP projects, mergers and acquisitions, tax combination and consolidation strategies. Sophie also advises Private Equity Houses in their French investment strategies. Before joining Deloitte in 2002, Sophie was a tax partner at Arthur Andersen. Sophie is attorney at Law, with a Business and tax Law degree obtained at Paris II University, as well as a finance and accounting degree obtained at Paris II. |

||