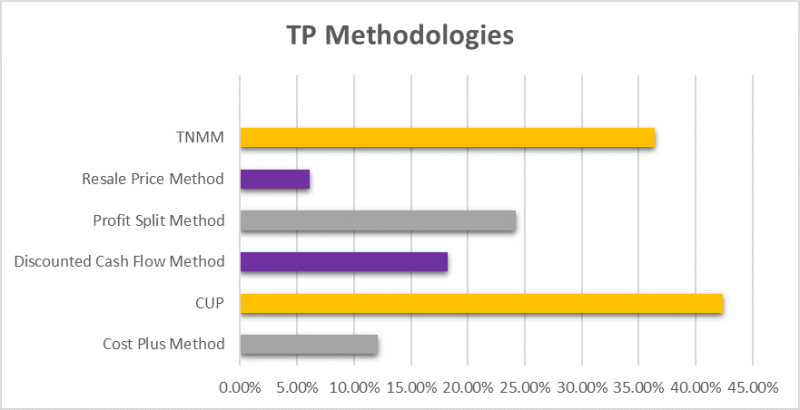

As part of the survey on IP management, TP Week and International Tax Review spoke to tax directors from 64 companies about transfer pricing methods. One of the most common methods of choice was the profit split at more than 24% opting for this strategy.

Many companies preferred to use the comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method, whereas a large number of businesses use the transactional net margin method (TNMM) to price IP assets. These more traditional methods are still very much in use, but others may be falling by the wayside. Profit splits may be the future in the digital tax debate.

Bill Sample, chair of the tax committee at the US Council of International Business (USCIB), is confident that the RPSM is the most accurate way to attribute non-routine profits. “If done right, the residual profit split can accommodate the need for simplicity in the inclusive framework,” he explained.

“It’s achievable because most non-routine profits that they want to split are in the larger developed countries earned by the larger, more complex multinationals,” Sample told TP Week. “Those companies should be able to handle that calculation.”

This shift is down to the BEPS project and other international efforts like the EU’s ATAD and US tax reform to combat the most aggressive forms of tax planning. However, the problem remains the lack of consensus and uniformity across the international tax system.

Complexity and uniformity

Residual profit splits are not the same as comparable profit splits or contribution profit splits. These methods all introduce more complex and time-consuming work to ensure businesses are fully above board. Yet these methods may be particularly well suited for some transactions.

“The profit split is for complex transactions, where you have unique contributions and it’s harder to find comparables,” explained one head of tax at a consumer goods company. “It will remain a niche method because of the level of complexity it is suited to, but it will become more and more common.”

“If you have a multilateral transaction, for instance, involving more than two countries, then it’s tricky to keep track of all the variables you need to take into account to apply a profit split,” the head of tax said. “But if it’s a bilateral transaction, involving two countries, then it’s much more manageable.”

Not only is the profit split better suited for complex, bilateral transactions, the method has made the process of getting advanced pricing agreements (APAs) much easier in certain countries. This is a crucial advantage in today’s uncertain market.

“When you have a difficult transaction where it could go either way, it’s better to just go with a profit split than any other method,” the head of tax said. “It’s much easier to go to the tax authorities and propose a clear 60/40 or 70/30 split.”

The biggest problem is the time factor. Most of the allocation keys are unavailable until after the end of the financial year, then tax departments have to retrace the company’s steps to get the full picture. Secondly, value chain analysis can take up a lot of time – it can be a matter of interviewing participants across the company’s business operations.

One mistake could set a company back by years. This may be why a third of companies said they had not changed their methodology after BEPS, although more than a fifth said they would do so in the future. The CUP method and TNMM are still widely used for good reasons.

At the same time, there are concerns over what the profit split will mean for businesses in the future. Many tax professionals fear the profit split will take the world of tax closer to a radically different apportionment model and increase the chances of double taxation.

“The profit split favours larger countries over smaller countries like Ireland,” one Irish tax advisor said. “We all agree that there is a profit split, but how do we split the profits? That is a fundamental question.”

“We might not get any portion of the profits from Airbus, even though we actually buy most of the aircraft,” he added. “There’s an argument for any tax position you want to justify.”

There is also a division among tax administrations. The tax authorities in countries like Germany tend to prefer profit splits, whereas the tax authorities in jurisdictions like Poland tend to be more traditional. This could force some companies to choose between methods.

On the other hand, there are also plenty of companies falling back on the profit split as a second line of defense. This is a trend becoming more prevalent in the world of tax since the BEPS project and US tax reform came into force.

“Some companies are mapping out different business units and entities that add value, playing around with potential profit splits because that could be handy in the future,” said one in-house tax consultant at a US biotech group.

“You keep the profit split method in the back of your pocket to feel more comfortable about your arrangements,” the consultant said. “It’s almost like an insurance policy.”

The world has become so uncertain for tax leaders that the best approach may be to take up the methods that once posed the biggest questions. The ground is still shifting beneath the feet of tax directors everywhere.

The full results of the effective IP management survey are available here.