Media company stock has appreciated about 43% over the last year, while one of the best performing stocks appreciated more than 58% since October 2007, according to Industry Group Tracker data published by The Wall Street Journal online on December 2013.

Driving the media industry's gains is a growing advertising revenue and the fact that digital distribution revenue is proving accretive, rather than, for example, cannibalising revenue from cable distribution. Companies in the media and entertainment space derive their revenues from a number of sources, such as selling advertising space, licensing original content, box office ticket sales, home video sales, on-line subscription revenues, pay-tv, video on demand, merchandising, amusement park admissions, and video game sales. All these sources at their core depend on one key ingredient – the companies' ability to attract viewers by creating valuable proprietary content and building popular brands.

Because the profits of diverse revenue streams are often recorded within disparate departments over the course of a long lifecycle, it is often difficult to accurately capture the full returns from proprietary content. While there are many other forms of intangible property that contribute to the success of the media and entertainment businesses, we will focus on intangible property that is most specific to the media and entertainment industry; that relate to content creation and monetisation. We will then discuss how these intangibles fit into the intercompany value chain and which factors to consider when determining appropriate compensation for these intangibles from a transfer pricing perspective.

What types of IP are important for media and entertainment companies?

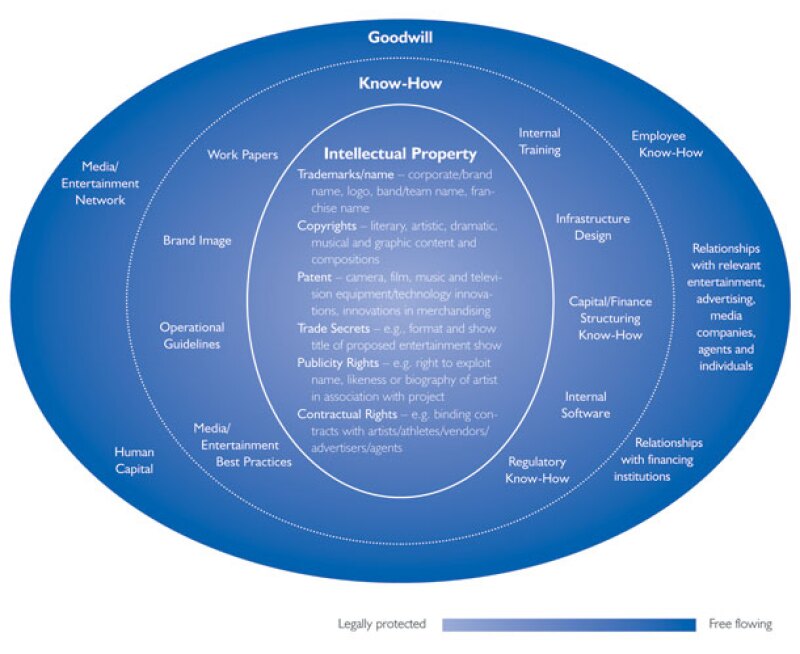

Intangible assets are frequently difficult to define precisely and can include both legally protected forms of intellectual property (IP) and the more ambiguous, but no less valuable, know-how and goodwill, as demonstrated in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1: Types of intangible assets |

|

For US transfer pricing purposes, US Treas. Reg. §1.482-4(b) defines an intangible as an asset that comprises any of the following items and has substantial value independent of the services of any individual:

Patents, inventions, formulae, processes, designs, patterns, or know-how;

Copyrights and literary, musical, or artistic compositions;

Trademarks, trade names, or brand names;

Franchises, licenses, or contracts;

Methods, programmes, systems, procedures, campaigns, surveys, studies, forecasts, estimates, customer lists, or technical data; and

Other similar items. For purposes of section 482, an item is considered similar to those listed in this section if it derives its value not from its physical attributes but from its intellectual content or other intangible properties.

Intangibles permeate each stage of the media and entertainment supply chain, from idea conception to content production, marketing, merchandising, distribution, packaging, and delivery.

For example, binding contracts with producers, actors, athletes, musicians, or other personalities, the know-how to structure upfront financing for the production, and the goodwill built up with financial institutions to raise the required capital are all critical to the financial success of movies and TV shows. With the increasing importance of digital content, libraries of proprietary software source code related to videogames, online media, and mobile applications are also increasingly valuable.

Once content is created, it must be marketed to spark the interest of both the distribution channels and end viewers, ensuring diverse streams of revenue going forward. These marketing activities may include ad campaigns, cobranding, theater launches, and merchandising. Success at this stage largely hinges on access to an extensive media and entertainment network, brand image, and relationships and contracts with vendors, advertisers, and personalities. And of course, merchandising deals are impossible without the rights to make and sell merchandise and to use the characters and any associated likeness, artwork, packaging, name, and logos.

Content is then distributed via a number of channels such as movie theaters, television broadcasting, retail locations, and the internet. A company's ability to distribute its content hinges on competing for, and securing the rights to, for example, license and distribute the content to third parties and having access to a strong distribution network, whether through direct ownership or relationships established with other distributors of content and institutions used to sell content (restaurants, sports leagues, print publications, website owners).

Finally, before the content can be exhibited via the various distribution channels, it often has to be packaged into complete branded channels, localised, combined with scheduled advertising, and transformed into the appropriate local format. Each of these steps requires the use of valuable intangible assets such as local insight about how to put together a channel to attract local audiences, the know-how and software to convert music, movies and television into different electronic formats, as well as the right to advertise on television, movies, radio, online media, and mobile applications.

As shown in Diagram 2, the largest media and entertainment companies straddle more than one stage of the supply chain and operate multiple businesses. Thus, these companies are better positioned to utilise multiple means of marketing to promote their products and attractions. The larger, more established companies enjoy other advantages as well. Larger companies in the filmed entertainment industry, for instance, have the ability to diversify their risk by developing a variety of projects and establishing stronger relationships with theater owners and TV networks. Larger companies also benefit from increased brand-name recognition, management experience, relationships with creative talent, and product distribution capabilities. The above factors contribute to the six largest film distributors making up 80% of US domestic box office revenues, according to Standard & Poor's Industry Surveys: Movies & Home Entertainment, September 13, 2012. For tax and transfer pricing professionals this structure frequently results in complex compensation structures reflecting the interplay of multiple categories of intangible assets that contribute to the overall success of the business.

Diagram 2: Diversified operations & assets of major media and entertainment companies |

||||||||

COMPANY |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

Basic Cable Network(s) |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

Billboards/Posters |

• |

• |

||||||

Book Publishing |

• |

• |

• |

• |

||||

Broadcast TV Network(s) |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|||

Broadcast TV Station(s) |

• |

• |

• |

• |

||||

Film Production/Library |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

Internet/Broadband Sites |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Magazines/Newspapers |

• |

• |

• |

|||||

Merchandising |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

Premium Cable Network(s) |

• |

• |

• |

|||||

Radio Stations/Networks |

• |

• |

||||||

Recorded Music Label(s) |

• |

• |

||||||

Theme Parks/Resorts |

• |

• |

||||||

TV Production/Library |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

Note: some relatively minor operations may be excluded. Includes significant equity interests in joint ventures or other companies. Source: S&P Capital IQ Equity Research |

||||||||

Typical transfer pricing structure

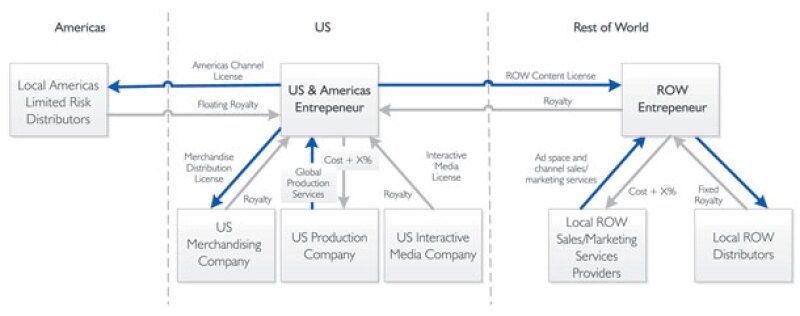

Diagram 3 shows a simplified example of a typical vertically integrated, US-based television production and distribution company, the international affiliates of which distribute content globally. Similar transaction flows are also common for movie studios.

The key functions, risks, and intercompany transactions of each entity type in this structure are described below.

Diagram 3 |

|

US and Americas entrepreneur

This entity houses the key global strategic decision-making functions, determining what content is produced and bearing the related risk. It owns the global brands, content, and other related intangible assets, engaging an affiliate to produce the content on a contract basis. For the US and sufficiently similar markets, such as the Americas, it packages the content into channels that are licensed to affiliates for distribution. For other markets that require more localisation, it licenses the content to be packaged locally.

US production company

This entity engages in content production activities on a contract basis for the US and Americas entrepreneur, either by performing the production activities or outsourcing them to a third party. From a transfer pricing perspective, those services are commonly compensated by reimbursing the cost incurred by the affiliate internally plus an arm's-length mark-up on the costs. Because any fees paid by the US production company to a third party are presumed to be at market price, no additional mark-up is applied to third-party costs.

US merchandising company

This entity engages in the US licensing and distribution, directly or through unrelated parties, of items related to the produced content. From a transfer pricing perspective, there is a payment, usually in the form of a royalty or license fee, from the merchandising company to the content owner.

US interactive media company

This entity provides an interactive gaming and entertainment platform. For example, there could be a cross-platform gaming initiative whereby characters will interact from a console game to multiple mobile and online applications. From a transfer pricing perspective, there is a payment, usually in the form of a royalty or license fee, from the US interactive media company to the content owner.

Local Americas limited-risk distributors

These entities license the complete packaged channels from the US and Americas entrepreneur and distribute them in their local country market. The affiliates collect payment from local third-party customers, retain a portion of the revenue targeting a predetermined arm's-length return, and remit the remainder of the revenue in the form of a floating royalty to the channel licensor. Limited-risk distributors have no control over the composition of the channels and generally execute the centrally developed marketing strategy, with some adaptation to local market conditions.

Rest of the World (ROW) Entrepreneur

This entity drives, funds, and conducts business operations outside the US and Americas region and houses the key ROW strategic decision-making functions, determining what content is licensed and bearing the related risk. This entity licenses ROW rights to the brands, content, and other related intangible assets, and may create central channels for some ROW markets, engaging local ROW sales/marketing service providers in such markets. In other markets, often ones requiring more substantial customisation of content mix, the ROW entrepreneur may sublicense the content rights to local ROW distributors.

Local ROW sales/marketing service providers

These entities provide sales and marketing services to the ROW entrepreneur in the local markets where the ROW entrepreneur is able to sell the centrally packaged channels directly to the local broadcasters. The service providers may be compensated by reimbursing the cost incurred by the affiliate internally plus an arm's-length mark-up on such costs.

Local ROW distributors

These entities sublicense content from the ROW entrepreneur as well as other third-party sources to create locally customised channels they then distribute locally. The local ROW distributors make strategic business decisions about the composition, sales, and marketing of the channels in their countries, and bear the related risks. They pay a fixed royalty for the rights to distribute the content.

What drives the value of content?

Whether licensing or selling intangible assets, or estimating compensation for a platform contribution transaction in a cost-sharing context, estimating the value of those assets is one of the most controversial and complex areas of transfer pricing. While there are many types of intangible assets used in the media and entertainment industry, content is the key value driver, a unique characteristic of this space.

The comparability guidance for the application of the comparable uncontrolled transaction method in Treas. Reg. §1.482-4(c) provides that the following factors, among others, are evaluated to determine the comparability of controlled and uncontrolled transactions. It may be inferred that these factors are expected to affect the transactions' market price:

Profit potential;

Terms of the transfer, including the exploitation rights granted in the intangible, the exclusive or nonexclusive character of any rights granted, any restrictions on use, or any limitations on the geographic area in which the rights may be exploited;

Uniqueness of the property and the period for which it remains unique, including the degree and duration of protection afforded to the property under the laws of the relevant countries;

Economic and product liability risks to be assumed by the transferee; and

Duration of the license, contract, or other agreement, and any termination or renegotiation rights.

These characteristics are of particular relevance for estimating the value of content. Specific examples from the media industry include:

Type of agreement: content may be licensed on a "spot" basis, with an individual price and agreement for each movie or TV series, or it may be licensed in bulk with the licensee committing to purchase a minimum amount or even all of a producer's content in a given year.

Producer: content price may be affected by the past performance, reputation, and strength of the network behind the studio producing this content. A studio with an extensive distribution network may be able to market and launch a show more effectively, attracting more viewers.

Content quality: the storyline, strength, and celebrity of the actors and directors, as well as the size of the studio's investment all affect the amount of interest a show or movie attracts, in turn driving higher revenues.

Exclusivity: exclusive licenses are generally considered more valuable, eliminating competition. Industry experience suggests that nonexclusive license rates may be as much as 50% lower than exclusive ones.

Age of content: newly released content is generally more valuable than older library content.

Type of content: reality TV shows are significantly cheaper to produce than scripted shows; furthermore, the level of competition and the size of the potential audience reached vary by genre, driving differences in value.

Popularity: movie popularity is widely evaluated based on box office receipts during an initial period after launch. Unlike movies, television shows do not have standard popularity metrics; however, IMDb, Nielsen, or other similar ratings could be used to gauge popularity. This could also be indirectly inferred based on when a show is aired: day-time or primetime.

Exploitation rights granted: there are as many different types of content distribution rights as there are distribution channels, and whether rights to distribute (via mobile devices, free TV, paid TV, electronic sell through, or video on demand) are included may affect price.

The impact of going digital

Sales channels are changing and the distribution of content is no longer tangible. Rather, most content today is distributed digitally and the question becomes how to characterise the local "distribution affiliates" of large media and entertainment conglomerates. Given that their functions remain broadly the same, and the only change has been a shift to digital distribution of content, have they now become service providers? They will no longer need to carry physical inventory, perform warehousing, or coordinate shipments; accounts receivable and accounts payable may be moved to the head office, with local affiliates providing local sales and marketing support. Because characterisation as a service provider typically provides less profit to the local affiliate than a distribution characterisation, this matter should not be neglected. We may expect to see more arguments for leaving a routine service provider return based on a mark-up on cost with the local affiliates in a digital world, and it is hard to see the arguments against the transfer pricing model shifting as the world is digitalising.

Decentralisation

As evident from our example, most content in the media and entertainment industry is produced and owned in the US, with eight of the top 10 global media companies being US based. However, due to the advent of new production technologies, increasing digitalisation of content, and globalisation, production costs and barriers to entry are declining. Even within established media companies, proprietary content can now be produced locally, targeting specific audience demands. The upcoming challenge for such companies will be how to effectively manage intangible assets when these are increasingly created in a decentralised manner across the globe.