The OECD's report, entitled Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 – 2015 Final Report, states that "digitalisation in the economy is occurring at a pace wherein the digital economy is increasingly becoming the economy itself". The scale and pace of digitalisation is putting pressure on tax administrations to undertake reform of the long-standing international tax framework.

Digitalisation has led to a wide range of tax challenges that cut across direct and indirect taxation and affect tax policy and tax administration alike. The OECD addressed this challenge in its Action 1 final report as part of its BEPS project at the request of the G20. Addressing the tax challenges raised by digitalisation remains a top priority for the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework.

The first finding agreed by all G20 and OECD Inclusive Framework countries under the BEPS project was that digitalisation is all-pervasive, making it difficult, if not impossible, to isolate the digital world from the rest of the economy. The same applies to taxation. Therefore, the OECD's Inclusive Framework work will affect all businesses, requiring an evaluation of the existing supply chain models, as it seeks to redesign the general profit allocation rules and establish minimum tax thresholds.

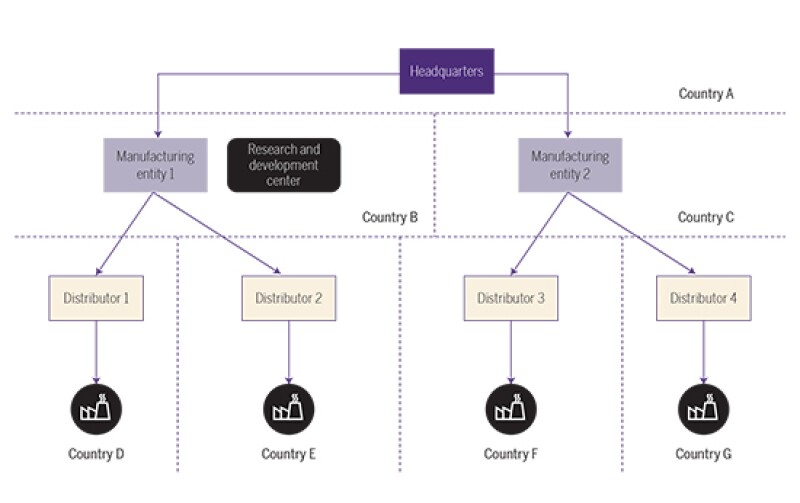

The industrial products and construction (IP&C) industry is an important sector in the economy of many countries. This industry comprises the engineering, manufacturing and distribution of capital goods and earth-moving and construction equipment. It also includes the aerospace and defence industry. IP&C businesses are generally capital- and labour-intensive (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Traditional supply chain for industrial products businesses

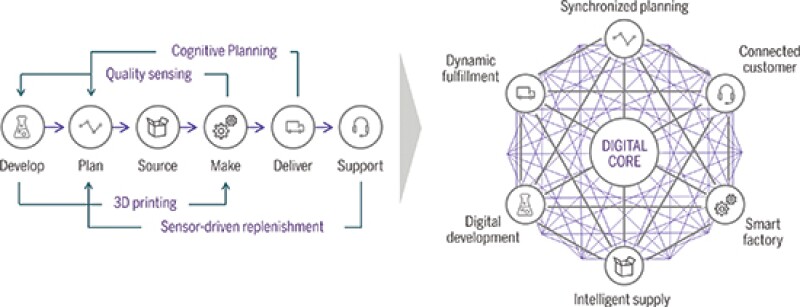

Figure 2: Digital supply networks

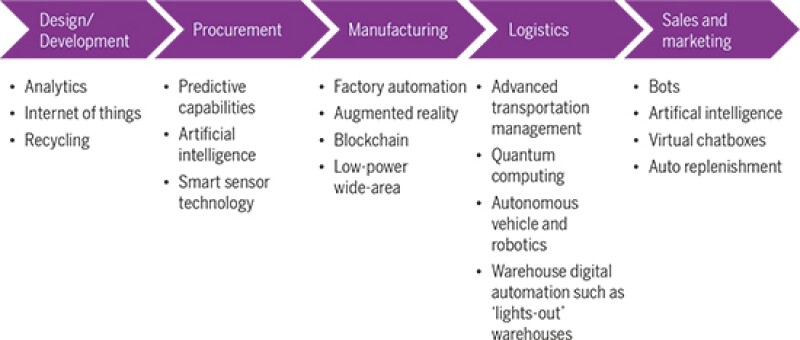

Figure 3: Digitalisation of industrial products industry

Traditional industrial products businesses are generally characterised by their presence in the form of manufacturing facilities, research and development centres, storage warehouses, distribution channels for supply and service centres, which provide support and after-sale services to customers.

Typically, manufacturing infrastructure is located in countries where the cost of labour is low, while research and development centres are located where skilled labour and technology are available. For distributors, warehouses and service centres are located in close proximity to customers; that is, in the countries where the market is located. A traditional supply chain follows a relatively rigid and linear path that moves information along with raw materials and semi-finished goods from one end of the production system to the other. The value drivers in the traditional supply chain for industrial products are usually procurement, manufacturing, research and development, logistics and distribution.

Now, the fourth industrial revolution technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), the internet of things (IoT), sensors, and robotics have given rise to digital supply networks (DSNs). These are transforming static, linear supply chains into an interconnected ecosystem of nodes that dynamically shapes the planning, production, and distribution of products. At the same time, customers are expecting more in terms of how they make purchases and engage with their value chain partners: more individualised products, more transparency in price and process, and personalised services delivered at a faster pace. Meeting and exceeding these new customer expectations requires an agile supplier value chain, one that can only be attained through a complex, interconnected network of DSN nodes working in concert. For organisations and customers alike, DSNs are ushering in a new era of digital fulfilment (see Figure 2).

With the advent of digitalisation, each value driver of the supply chain will undergo a transformation, which will enable a seamless experience in the running of industrial products businesses. Some of the key digitalisation transformations in the industrial products industry are provided in Figure 3.

With digitalisation allowing business activities to spread across the globe, it is becoming increasingly complex to identify the location of value drivers and to decide how to allocate profits.

As can be observed from the written comments to the public consultation document received from businesses operating not only in highly digitalised business but also in automotive, oil and gas, pharmaceuticals and financial services, it is clear that the OECD work on the digital economy has an impact on multinational enterprises across all industries, including IP&C. The OECD is exploring several approaches on a 'without prejudice basis' as presented in the Programme of Work to Develop a Consensus Solution to the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy. These are grouped into two pillars:

Pillar One: This pillar deals with the allocation of taxing rights to market jurisdictions and focuses on the concurrent revision of allocation and nexus rules. It intends to go beyond the arm's-length principle and the physical presence requirement. This approach is moving into a new realm, where physical presence is not required and the arm's-length standard is not strictly followed.

Pillar Two: This pillar focuses on other novel forms of taxation. The second pillar seeks to address the remaining BEPS risks of profit shifting to entities subject to no or very low taxation through anti-BEPS rules, including an income inclusion rule and a tax on base-eroding payments.

Given that the above proposals have the potential to dramatically change international tax rules, there are certain guiding principles the G20 has committed to: preventing double taxation, simplicity, certainty, a level playing field between jurisdictions, and the elimination of ring-fencing the digital economy.

To be aligned with the two pillars, the public consultation document released in early 2019 dealt with three types of proposals around profit allocation and nexus.

Three proposals for profit allocation and nexus

The user participation proposal focuses on the value created through developing a user base and soliciting data and content from them. This proposal is applicable to those businesses where user participation is a critical component of value creation: social media platforms, search engines, online marketplaces, etc.

The Inclusive Framework recognises that this is a ring-fenced proposal and that there would be no change in the profit allocation and nexus rules under the user participation proposal for businesses following traditional models.

The marketing intangibles proposal addresses a situation whereby an MNE group reaches a jurisdiction either remotely or through a limited local presence to develop a user base and marketing intangible. Marketing intangibles would include not only brand/tradenames but also customer goodwill in market jurisdictions.

The marketing intangibles proposal has a wider reach and would affect IP&C companies. As mentioned before, a traditional supply chain in the IP&C industry resembles a relatively rigid and linear path that moves information along with raw materials and semi-finished goods from one end of the production system to the other.

Often, in the IP&C industry (primarily B2B models), production planning, strategic research and development, marketing and sales strategy, often developed by a central company, are typically attributed most of the business value. Local sales activities and the functions regarding customer support are regarded as routine in nature and earn lower returns.

The work of the OECD Inclusive Framework on the digital economy would lead to a shift from solely the arm's-length standard to allocating an element of non-routine profits to market jurisdictions. This proposal contemplates the notion that marketing intangibles are created in a market jurisdiction through active participation and intervention of the business in that market jurisdiction.

In the IP&C industry, trade intangibles in the form of technical know-how, trade secrets and licences, etc. bring significant value to the business apart from and relative to marketing intangibles. To allocate non-routine profits appropriately, it would be necessary to distinguish between trade intangibles and marketing intangibles.

Moreover, there is significant investment in research and development (R&D) by businesses in the IP&C industry. Continuous investment in R&D helps them to maintain efficiency and quality of products/solutions, which is important to create a positive attitude in customers' minds. Application of the marketing intangible model may result in a disproportionate reduction in the profits allocated to the rest of the value chain, because the IP&C industry is predominantly a B2B model with lesser intensity of advertising, marketing and promotion functions. A balance would have to be struck in relation to other value-creating activities to ensure that any new framework does not tilt taxable profits towards market countries and costs/losses towards countries contributing to significant people functions.

The OECD's Inclusive Framework also proposes a concept based on a 'significant economic presence'. It suggests that taxable presence in a jurisdiction would arise when a non-resident business has a significant economic presence on the basis of factors that evidence a purposeful and sustained interaction with the jurisdiction via digital technology and other automated means. The proposal contemplates that the allocation of profit to a significant economic presence could be based on the fractional apportionment method.

The framework recognises the following would be sufficient to create a significant economic presence:

The existence of a user base and the associated data input;

The volume of digital content derived from the jurisdiction;

Billing and collection in local currency or with a local form of payment;

The maintenance of a website in a local language;

Responsibility for the final delivery of goods to customers or the provision by the enterprise of other support services such as after-sales service or repairs and maintenance; or

Sustained marketing and sales promotion activities, either online or otherwise, to attract customers.

Traditionally, IP&C companies have a local presence for revenue-generating activity. With the traditional model of doing business, the significant economic presence concept would not have a substantial impact on IP&C companies. Having said this, globalisation and digitalisation are megatrends for IP&C companies. The use of digital technologies will gradually change the way IP&C business is conducted and will give rise to a variety of business models that are absent in the traditional economy. IP&C businesses are digitally reinventing themselves to enable new efficiencies and opportunities. Some of the significant digital technologies proposed to be adopted by IP&C businesses include: AI and analytics, automation and advanced robotics, additive manufacturing and 3D printing, cloud and IoT.

The digital transformation of the IP&C industry makes its supply chain more flexible and turns it into an interconnected matrix that allows data and goods to move non-linearly to maximise efficiency and to meet changing consumer and market demands.

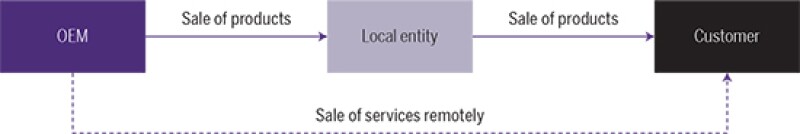

Over the next decade, with Industry 4.0, business models will be digitised and will adopt digital supply chains. This will shift focus from physical to digital value drivers, which may require no physical presence entailing significant people functions in the market jurisdiction. An example of a new business model is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: New business model

The above three proposals deal with both allocating taxing rights and nexus rules. The OECD took a step forward to build a work plan, its programme of work, whereby the two workstreams of allocation of taxing rights and nexus rules have been bifurcated under proposals named Pillar One (Pillar Two proposals deal with global anti-base erosion).

The Inclusive Framework identified several technical issues that need to be resolved under the programme, which can be grouped into three building blocks: new profit allocation rules; new nexus rules; and implementation.

New profit allocation and nexus rules

The programme of work includes the following three proposals on new profit allocation rules:

The modified residual profit split method;

The fractional apportionment method; and

A distribution-based approach.

These approaches have a common design whereby they consider a business' total profits and contemplate the use of certain simple, formulaic assumptions. By definition, these approaches are not synchronised with the arm's-length model. These proposals are 'in principle' proposals, and hence the drafters have not delved into a numerical or an economic analysis. These are concepts that will be fleshed out in more detail in the coming months. It will either be a single approach or a combination.

These approaches will impact MNEs across all industries. The first issue is complexity. The above approaches will require new information to be collected and reported. The systems that collect and manage financial and other data may have to be reconfigured. Another consideration would be business line and regional segmentation. Many MNEs in the IP&C industry cater to different segments/products; they have various business lines and varying levels of operating profitability. Entity-level profits may lead to concerns regarding the reliability of data, which in turn may lead to unintended outcomes and distortion. Finally, in the IP&C industry, there are several key value creators apart from the marketing function, including R&D/product innovation, design and value engineering. It would be imperative for the new profit allocation rules to compensate all key value creators.

The proposed nexus rules explore the concept of remote taxable presence (that is, a taxable presence without traditional physical presence) and a new set of standards for identifying when such a remote taxable presence exists. The proposed nexus rules supplement the new profit allocation rules by presuming a deemed presence in whose hands the profit allocated to the market jurisdiction will be taxed.

The proposal for establishing nexus contemplates revenue thresholds for determining significant economic presence. In the IP&C industry, the typical model MNEs follow is the sale of products from manufactures to distributors, who in turn generate sales from ultimate customers. The new nexus rules may lead to an unnecessary compliance burden by creating a presence when there may be no or low additional profit allocable to that presence.

Implementing new taxing rights

The new profit allocation rules and nexus rules that give rise to new taxing rights will form an extra layer of rules within the tax framework, increasing the administrative burden and potentially increasing the risk of double taxation. The OECD Inclusive Framework proposes to assess the effectiveness of existing treaty provisions and has made it clear that changes and enhancements to the dispute prevention and resolution procedures will be a necessary part of the programme of work.

The above proposals seeking allocation of new taxing rights would require changes to tax treaties if they are to be successfully implemented. The program suggests considering amending or supplementing the multilateral instrument (MLI) or establishing a new multilateral convention to reflect suggested proposals.

To summarise, digital transformation is occurring at an unprecedented pace across industries. For example, the first functional 3D-printed office building was constructed in Dubai and required only 17 days to print and two days to assemble. The project cost – building and labour costs – were reduced by 50%. The IoT is enabling businesses to provide customised climate control, lighting and security solutions at scale, for example, by detecting the people present in a room and their location, and thereby building a concurrent data pool. Given this, digitalisation is leading to change in the key value drivers of businesses (in the above example, the traditional installation function, which was labour intensive, was one of the key value driver of the business). Hence, a clear understanding of what is coming and its implications is essential. Once the above proposals are crystallised by 2020, the impact of revised tax rules on the IP&C industry will become apparent.

Based on the current transfer pricing rules, MNEs operating in this industry are taxed in jurisdictions where key value functions reside. Marketing is not the only key value activity in a B2B model. Hence, one needs to consider whether it is appropriate that there be differentiated allocation and nexus rules for B2B and B2C models.

MNEs should be prepared

The proposals that have been put forth are based on the common assumption that existing transfer pricing rules are not adapted to capture value created by remote participation through digital transformation. There is alongside this a recognition that market jurisdictions should get a reward even when valuable functions are located elsewhere.

It is likely that the OECD may come up with a threshold (similar to the threshold for requirement of country-by-country reporting requirements) to restrict proposals to only large groups. In addition, a few countries have already proposed or implemented changes to their domestic tax regimes to include taxing of digital businesses through an equalisation levy, digital services tax, and other mechanisms.

It is important for MNEs to undertake an evaluation of each proposal in detail and assess its impact on their business models. Businesses should also be encouraged to keep the launch of new business models agile, so as to cope with the looming uncertainty over tax matters and their resolution in all relevant jurisdictions.

MNEs may also discuss the impact of their assessment with their respective governments to ensure that it is adequately considered. This will help governments to contribute to and establish their position.

With the OECD's ambitious plan on getting a consensus solution by 2020, MNEs will have limited time to assess the impact of these proposals on their existing business models. However, with the next public consultation expected in autumn 2019, it is important for MNEs to take the opportunity to actively engage in the discussion as a consensus-based solution is developed.

Tehmina Sharma |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Deloitte India T: +91 22 6185 4318 Tehmina Sharma is a partner in Deloitte India. Tehmina has more than 20 years of experience in direct tax, international tax and transfer pricing. She leads the energy natural resources and industrial products practice within transfer pricing. She is responsible for transfer pricing, advance pricing agreements (APAs), mutual agreement procedure projects and tax policy initiatives, including on BEPS. She was seconded to Deloitte US (Los Angeles) for 18 months and has worked on restructuring, IP planning and immigration and the restructuring of the function and risk profiles of group entities of clients of Deloitte US. Tehmina is a frequent speaker at TP conferences. She is a fellow member of The Institute of Chartered Accountants in India and has a master's in business management. |

Riddhi Shah |

|

|---|---|

|

Senior manager Deloitte India T: +91 22 6245 1366 Riddhi Shah has more than 10 years of experience, having worked in TP practices in India and Singapore. Riddhi has served clients across industries. Her current focus is energy, natural resources and industrial products. She is actively engaged in TP compliance, BEPS compliance, audits and litigation. Her key assignments include assisting multinational companies in achieving unilateral/bilateral advance pricing agreements (APAs) and mutual agreement procedure (MAP) resolutions. She has written many articles related to transfer pricing and is a regular speaker at tax conferences and events in India. She is a member of Institute of Chartered Accountants of India and Institute of Cost and Works Accountants of India. |

© 2019. For information, contact Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited.

This communication contains general information only, and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, its member firms or their related entities (collectively, the ‘Deloitte network’) is, by means of this communication, rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your finances or your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser. No entity in the Deloitte network shall be responsible for any loss whatsoever sustained by any person who relies on this communication.