Recent years have seen a reduction in foreign direct investment (FDI) flows across the world. China's inbound FDI has held up reasonably well, but outbound direct investment (ODI) has reduced.

In 2016, Chinese ODI reached its peak to-date ($196.1 billion), with a drop in 2017 ($158.3 billion) and 2018 ($129.8 billion); in 2019 $78.5 billion of non-financial ODI was recorded from January to September. As noted in the Financial Times (The story of China's great corporate sell-off, September 20 2019), Chinese companies in 2019 became net sellers of global assets for the first time since they became major players in global M&A. The record sell-off has totalled approximately $40 billion for the year-to-date, according to data from Dealogic. This being said, there are a number of fields in which Chinese ODI continues to grow.

In 2018, the China Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) statistics indicated that Chinese enterprises invested $15.6 billion in jurisdictions covered by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), meaning an increase of 8.9% on the prior year. Key investment destinations include Singapore, Laos, Vietnam, Indonesia, Pakistan, Malaysia, Russia, Cambodia, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates.

While MOFCOM figures show BRI accounting for 13% of total mainland China ODI, this does not capture the very significant amount of mainland China-BRI investment that goes via Hong Kong SAR and several Caribbean jurisdictions. Certain economic research institutes estimate the figure could now be as high as 21.6%. Growth has appeared to continue, both in terms of ODI in the BRI countries and in terms of the number of new engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) projects; there were 3,642 new BRI EPC contracts new signed in 2019 to-date, according to MOFCOM.

Of significant concern is that there are some key uncertainties that are looming over Chinese outbound tax planning. Tax certainty means that enterprises have the capacity to make an accurate assessment of the tax and compliance costs associated with an investment in a country over its lifecycle. High levels of tax uncertainty are seen to raise risk premiums and hurdle rates for investments – to the extent that Chinese outbound investing enterprises face deeper tax uncertainty, this means that potentially worthwhile investments may not be undertaken.

The past year has seen a number of developments in both the tax and non-tax arenas that may raise uncertainty and impact the investment plans and operating structures of China multinational enterprises (MNEs), among others. The most significant in this regard include:

The new economic substance requirements in various offshore jurisdictions, which have been used extensively by Chinese MNEs for their overseas investments;

The EU Mandatory Disclosure Regime, which impacts planning arrangements by Chinese MNEs in relation to their extensive investments in the EU;

Brexit and its implications for significant Chinese investments in the UK; and

The BRI Tax Administration Cooperation Mechanism (BRITACOM), as a basis for addressing tax uncertainty in China's most promising investment locations for the future.

Other key issues impacting on Chinese outbound investment, including developments with the China mutual agreement procedure (MAP), advance pricing agreements (APA), and the emerging new global tax framework, are explored in the transfer pricing (TP) and international tax articles in this edition.

Offshore uncertainties

The first uncertainty comes in the form of the new economic substance requirements in offshore jurisdictions.

Chinese MNEs investing overseas, frequently set up entities in low-tax offshore jurisdictions as vehicles for investment in target markets. This is done for a variety of commercial and legal reasons. For example, a holding company could be set up in the Cayman Islands with the aim of facilitating a future initial public offering (IPO) in either the US or Hong Kong SAR. Holding companies may be set up in United Arab Emirates (UAE) to facilitate the regional management of the business and/or investments in the Middle East. For certain sectors (technology, media and telecoms (TMT), energy, etc.), entities in the Cayman Islands are used to hold intellectual property, or as a firewall to separate the potential legal risk of the underlying operations/assets from the Chinese companies or their immediate holding entities.

In recent times, however, the traditional low-tax jurisdictions have been compelled to introduce economic substance requirements. This is due to both the establishment of the EU blacklist of non-cooperative jurisdictions, and the expansion of OECD/Forum on Harmful Tax Practice peer review under BEPS Action 5 to cover low substance arrangements in offshore jurisdictions. The details of the new rules are explored in further detail in Offshore economic substance laws: Implications for Hong Kong SAR's funds sector.

Jurisdictions where new and stringent substance compliance requirements must be met include Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Cayman Islands, UAE, Guernsey and Jersey. Entities in these jurisdictions may need to increase their local physical presence, in terms of activities, local expenditure, and recruitment of local employees, in order to comply with the new requirements.

While there are local variations in the requirements, they are broadly equivalent across each of the offshore jurisdictions. Substance requirements took effect from January 1 2019, with a six-month grace period given to existing entities to meet the requirements. Chinese investors that have intermediary holding companies in those jurisdictions (especially BVI or Cayman Islands), should evaluate, on an ongoing basis, the use of such jurisdictions in their investment/operating structures and apply cost-benefit analysis to assess possible needs for adaptation.

The EU is still reviewing the legislation enacted by the various offshore jurisdictions to test whether their new substance measures meet the EU's 'fair taxation' principles. As such, additional guidance notices may be issued in relation to the implementation of these rules. Furthermore, international efforts to establish a new global tax framework are examining the potential to deploy a global minimum tax across all countries (pillar two of the Inclusive Framework global consensus solution to the tax challenges of digitalisation). If these rules are instituted, it would have an even more profound effect on the use of offshore jurisdictions than the substance requirements noted above. Chinese enterprises would need to give refreshed consideration to their structures at that point; for more detail, read BEPS 2.0: What will it mean for China?.

Tax reporting and Brexit

The EU Mandatory Disclosure Regime (MDR) brings a new dynamic for Chinese enterprises which have operations/investments in Europe. The MDR aims to combat aggressive tax planning/structures mainly driven by tax considerations, and Chinese businesses will need to consider the potential impact on their existing structures.

The EU directive establishing MDR (Directive 2011/16/EU, referred to as DAC6) entered into force in June 2018, and requires EU member states to have national regulations in place by December 2019, with information exchanges to commence from October 2020. The MDR requires intermediaries, such as tax advisors, accountants and lawyers, to disclose potentially aggressive tax planning arrangements. It also establishes the means for tax administrations to exchange information on these structures.

However, not every cross-border arrangement would be reportable; the obligation is limited to arrangements that fall within a set of so-called 'hallmarks' and a 'main benefits' test, which are set out in DAC6. In certain cases, if there are no intermediaries that are responsible for the required reporting, the reporting obligation would shift to the taxpayers themselves.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the disclosure requirements have retroactive effect: reportable cross-border arrangements (where the first steps are implemented between the date when DAC6 enters into force – during the period June 25 2018 to July 1 2020) must also be reported during July 1 2020 and August 31 2020. In this connection, it is imperative for intermediaries and taxpayers (including Chinese enterprises) to start reviewing and assessing the requirements of DAC6, even in the absence of a specific transposition law.

Any reportable or potentially reportable arrangements/transactions should be documented as a precautionary measure to comply with the retroactive reporting obligations. Alternatively, Chinese enterprises should also consider whether any changes to their structures (which fall within the above reporting requirements) should be made or not.

In relation to Brexit, the UK has long been viewed as a highly attractive destination for Chinese investment. In 2018, the UK was reportedly the largest recipient of Chinese ODI worth $4.9 billion, followed by $4.8 billion in the US and $4 billion in Sweden. The tax implications of Brexit are being followed closely by Chinese investors keen to mitigate the impact on their European operations run out of the UK and the value of their investments. Potential tax implications being focused on by Chinese investors:

Where EU directives, including the Parent-Subsidiary and Interest and Royalties Directives, no longer apply to UK enterprises, the latter may need to rely on double tax agreements (DTAs) to reduce WHT exposures.

Possible limitations on the free circulation of goods between the UK and other EU member states, and new technical and administrative complications for VAT and customs, are being followed closely by Chinese enterprises, along with transitional arrangements negotiated.

Chinese MNEs are reviewing the exposures of UK entities they have established or acquired to see if structure adaptations are required.

BRITACOM

In last year's article Tax opportunities and challenges for China in the BRI era, we detailed initial efforts to drive tax administrative collaboration between BRI countries. These efforts were motivated by a number of particular challenges for investors from China and other BRI countries.

These included uncertain tax policy design and tax administrative practices. For example, tax uncertainties arising from poorly drafted, unclear or complex tax rules, unpredictable or inconsistent treatments by tax authorities, and high levels of bureaucracy for tax compliance, etc.

We also noted an inconsistent approach to applying international tax standards. For example, in the application, by local tax authorities, of cross-border tax rules in a manner inconsistent with international tax standards, including permanent establishment (PE) assertions and profit attributions, or TP adjustments, etc. In addition, we highlighted issues with dispute prevention and dispute resolution mechanisms, such as a lack of access to rulings, APA and MAPs, and lack of resources to administer, etc.

In April 2019, the BRI governments sought to take these efforts further with the first BRI Tax Administration Cooperation Forum Conference (BRITACOF), held in Wuzhen, China. This was attended by heads of tax administrations and representatives of international organisations, academia and the business community, and saw the launch of BRITACOM as a structured institutional solution to establish a sound and friendly BRI tax environment.

BRITACOM has set out five dimensions for tax cooperation, being: (i) following the rule of law in taxation; (ii) expediting tax dispute settlement; (iii) improving tax certainty; (iv) streamlining tax compliance and digitalising tax administration; and (v) enhancing administration.

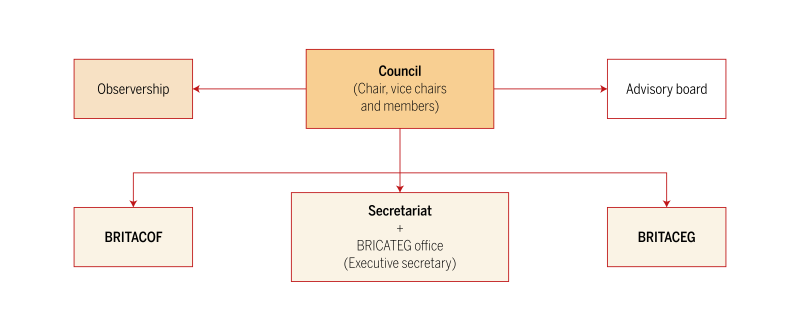

The governance structure of BRITACOM consists of the Council, Secretariat, BRI Tax Administration Cooperation Forum (BRITACOF), BRI Tax Administration Capacity Enhancement Group (BRITACEG) and the Advisory Board (see Figure 1):

Figure 1 – The governance structure of BRITACOM

The Council is the decision-making body and in charge of personnel arrangements, strategic decisions, and coordination of BRITACOF and BRITACEG;

The Secretariat supports the routine operations of the Council, BRITACOF and BRITACEG (e.g. regulation drafting, internal administration issues);

BRITACOF is the annual meeting of BRITACOM, and a permanent platform of dialogue on tax matters;

BRITACEG is a network consisting of BRITACOM member competent tax authorities and certain observers. It is intended to drive collective tax policy research, mutual technical assistance and tax training; and

The Advisory Board includes representatives of the business community, international organisations and academics. It provides strategic advice drawing on international expertise and experience.

At present, Chinese investment in the BRI countries is mainly focused in the infrastructure sector. With the steady improvement of BRI infrastructure and interconnectivity over time, it is anticipated that BRI countries will attract further investment in other traditional and emerging sectors, for example consumer markets, innovative financing, and TMT. Early moves through BRITACOM, including the policy research and coordination efforts of BRITACEG, to resolve intra-BRI tax frictions and uncertainties should lay the groundwork for this coming stage of investment. This may include efforts to encourage and support the adoption of international tax standards across BRI countries, updating of BRI tax treaties, streamlining tax administration, and enhanced mechanisms to deal with tax dispute prevention and resolution.

The authors would like to thank Yi Zhang, senior tax manager in the Beijing office, for her contribution to this article.

Michael Wong |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China Beijing Tel: +86 10 8508 7085 Michael Wong is a partner and the national leader of deal advisory, M&A tax for KPMG China. He is based in Beijing and focuses on serving state-owned and private Chinese companies in relation to their outbound investments. Michael has extensive experience leading global teams to assist Chinese state-owned and private companies on large-scale overseas M&A transactions in various sectors, including oil and gas, power and utilities, mining, financial services, manufacturing and infrastructure. |

Joseph Tam |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China Beijing Tel: +86 10 8508 7605 Joseph Tam is a tax partner at KPMG specialising in advising Chinese clients on tax issues arising from their overseas business operations and/or investments. Joseph has advised clients on tax structuring, tax due diligence, tax modelling review, sales and purchase agreement (SPA) negotiation, corporate restructuring, etc. Joseph has also assisted clients in applying for tax incentives and advance tax rulings. Joseph services clients in a wide range of industries, including infrastructure, power and utilities, industrial markets, TMT and financial services. He is a frequent speaker at seminars on Chinese outbound investment, the Belt and Road Initiative and international production capacity cooperation. He is also a member of the Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants. |