Italy ranks highly in the interest of international investors, who in particular are intrigued about the country's northern regions and Milan, where they show a special focus on real estate, retail and the work of innovative small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

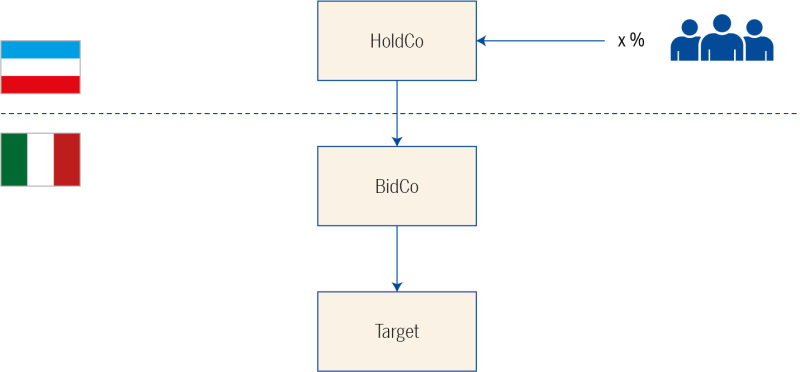

Italian tax rules are organised in order to set a contraposition between the seller and purchaser about 'share deals' and 'asset deals'. The financial industry has developed a common deal structuring with the use of leveraged buyouts (LBO). In particular, the Italian Tax Office (ITO) with Circular Letter No. 6/E of March 30 2016, set the LBO steps as follows:

a) A foreign holding company (HoldCo) is incorporated by the purchaser;

b) HoldCo sets up an Italian bid company (BidCo); this company is organised with a class of shares and 'quasi-equity' or debt categories.

c) Finally, BidCo makes the acquisition of the target company or directly acquires the target asset and liabilities. Usually, when a share purchase is involved, the final step is the combination between BidCo and Target – a merger leveraged buyout (MLBO) (see Figure 1).

A specific path is provided by the Italian Civil Code. Tax rules are quite strict about a possible participation exemption/non-participation exemption arbitration or about passive interest deductions.

Figure 1 – A merger leveraged buyout when a share purchase is involved

International regulation

International regulations are increasingly playing a role in private equity transactions in Italy through LBO structures. Tax transparency is increasingly more effective because of the common reporting standard (CRS) and the US Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), which imposes a clearer understanding of the different players and investors involved. The Italian regulators, Italian Companies and Exchange Commission (Consob), the Bank of Italy and the professional firms are subject to the substantial addition of information in the case of non-institutional investors and trusts or similar entities. Anti-money laundering (AML) rules are also fully implemented, with the completion of the ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) register to happen in the near future.

In regard to international tax, a central role is played by the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directives (ATAD) and the mandatory disclosure rule (MDR).

EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directives

Last year, two EU directives 2016/164 (ATAD 1) and 2017/952 (ATAD 2) were implemented in Italy by Decree No. 142 of November 29 2018, which entered into force in January 2019.

In brief, the provisions introduced by the ATAD will impact the following areas.

Controlled foreign corporation (CFC) rules

A CFC refers to an entity or a permanent establishment (PE) that meets the following conditions:

i) A taxpayer that alone, or together with associated companies, holds a direct or indirect participation of more than 50% of the voting rights, more than 50% in the capital or the entitlement to more than 50% of the profits of that entity;

ii) The actual tax paid by the entity in the CFC jurisdiction is lower than the difference between the corporate tax that would have been charged on the entity or PE under the applicable corporate tax system in the member state of the taxpayer and the actual tax paid on profits in the CFC jurisdiction;

iii) More than on third of income is represented by:

1) interest or any other income from financial assets;

2) royalties or any income from intellectual property;

3) dividends or any income from the disposal of shares;

4) income from financial leasing;

5) income from insurance, banking and other financial activities; and

6) income from invoicing associated enterprises in regard to goods and services, where there is a little economic value added.

Interest deductions

The deduction of exceeding borrowing costs is limited to 30% of taxable earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA).

Exit tax

The ATAD introduces an EU-wide exit tax aimed at preventing tax-base erosion by jurisdiction transfers while leaving ownership unchanged. The exit tax can be deferred by the taxpayer by paying it in instalments over at least five years if certain conditions are met. It should be noted that the five years' instalments of the tax debt may become immediately recoverable if:

The transferred assets are transferred to a non-EU country or a European Economic Agreement (EEA) country;

The taxpayer's residence or its PE is subsequently transferred to a non-EU country (or EEA country); or

The taxpayer goes bankrupt or is wound up.

The mandatory disclosure rule

In order to identify aggressive tax planning practices, the EU tax authorities worked together to expand the application of the automatic exchange of information (AEOI).

In this context, the DAC6 (Directive on Administrative Co-operation 2018/822/EU) of May 25 2018 – also identified as the "tax intermediaries' directive" or "mandatory disclosure" – represents the last step of tax compliance. It is strictly related to the OECD G20 BEPS project and in particular to Action 12, as well as the OECD document on 'Mandatory Disclosure Rules for CRS Avoidance Arrangements and Opaque Offshore Structures'.

DAC6 provides for a (i) duty to report some cross-border tax mechanisms to the local tax authorities, which are potentially aggressive and meet certain criteria (reportable cross-border arrangements); and (ii) automatic exchange of information between EU tax authorities.

EU directives between related parties

The Parent-Subsidiary Directive (PSD) is designed to eliminate tax obstacles in profit distributions between groups of companies within the EU by:

Removing withholding taxes on payments of dividends between affiliated companies of different EU member states; and

Preventing double taxation of parent companies on the profits of their subsidiaries.

The Interest and Royalties Directive aims to eliminate withholding tax obstacles in the area of cross-border interest and royalty payments within a group of companies by abolishing:

Withholding taxes on royalty payments arising in a member state; and

Withholding taxes on interest payments arising in a member state.

The benefits of both the Parent-Subsidiary Directive and Interest and Royalties Directive are only granted to companies that are compliant with the following requirements:

Subject to corporate tax in the EU;

Tax resident in an EU member state;

Of a type listed in the annex to the directive; and

The company receiving the incomes must be the beneficial owner.

Particular attention must be given on structuring for a non-EU investor.

Substance over form

The above mentioned EU directives are also aligned with the beneficial owner principle and therefore that substance prevails over form.

When the control of the Italian entities is made through a foreign holding company, the analysis of the HoldCo must be done in order to verify if it can be considered as a sheer conduit or as a real business.

The Circular Letter No. 6/E of March 30 2016 (issued by the Italian association of joint stock companies – Assonime) highlighted the multi-role profile of the HoldCo in an international business. In particular, HoldCo can be:

Legitimately used by multinational corporations to organise liabilities and business, in ways capable of optimising the mode of operations of the corporate governance structure, and facilitating the acquisition and disposal of business units located in the various countries.

The HoldCo may also carry out activities not directly related to the primary function of holding qualified shareholdings, including the provision of services intra-group, treasury activities and management of the group's intangible assets.

In cases C-116/16 and C-117/16 of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), the court introduced a notion of 'abuse'.

In particular, the CJEU indicated a set of indicia which the national courts must consider in assessing whether a transaction is abusive, such as in cases where:

The immediate recipient only plays a conduit role and is obliged to pass the income on entities established in third countries that would been taxed in the state of source had they received the payments directly;

The immediate recipient lacks an economic substance and carries out very limited activities.

In addition, it is important to recall what was clarified in the Italian Supreme Court decision (No. 25490 of October 10 2019). The Supreme Court defined some rules with regard to the conditions related to accessing the benefits of the EU treaty.

The Supreme Court ruled that in order to identify the country of establishment of the companies, what matters is the place of effective management, as provided by Article 4, paragraph 3 of the OECD Model Income Tax Convention.

The Supreme Court seems to be pleased to interpret the provisions of the directive as requiring that the recipient of the dividend be actually established and effectively managed in its EU country of organisation, for it to be considered a genuine arrangement duly eligible for the withholding tax exemption.

Indeed, the court also clarified that the benefits of the directives should be denied if the EU recipient of the dividend is a company owned or controlled by a company established in a third state, and the EU company has been organised for the sole or main purpose of obtaining the directive's withholding tax exemption.

The private equity fund

It is important to underline the central role of holding companies as a beneficial owner. If the holding company is not to be recognised as a beneficial owner (for example because of its nature of a conduit), a look-through approach must be used to identify the effective beneficial owner.

We often see private equity funds structured as a limited partnership. This might entail that the fund itself should be considered transparent for tax purposes and, as a consequence, they cannot access the EU directives' benefits. Considering those principles, it may therefore be best to test and assess the actual investment structure in order to understand whether or not the EU principles are fulfilled. The structure of HoldCo as a real business or as a governance entity upon real business must be verified in order to avoid the arrangement of abusive planning.

A different situation is to be analysed before collective investment vehicles (CIV) testing if it is considered the beneficial owner. If so, the application of the EU directive could be achieved.

Share deal vs asset deal

For an investor structuring a deal, it is important to consider its mechanics and its tax impacts. In Italy, the best practices usually follow the path of:

An acquisition of the business (assets and liabilities) from the operating corporation (asset deal); or

An acquisition of the shares of the operating corporation from the corporation's shareholders (share deal).

The choice of the structure depends on different elements.

In a share deal:

The seller usually has an advantage on tax expenditure, if compared with an asset deal;

The purchaser will acquire the company, including all of its related liabilities;

The purchaser may entail a difference between the cost of the participation and net-assets of the target; and

With a LBO, the merger would bring out the gap and the debt is transferred to the new company. Generally, the merger is tax neutral and no tax effect is possible to be transferred to assets. The above, with the exception of a revaluation process, bears additional costs and rules. On debt structuring, there is impact on the deduction of interest, following thin capitalisation rules.

In an asset deal:

The purchaser will pay the price of the company assets plus goodwill and the price can be amortised, generally for 18 years but with consistent time reduction for some asset categories. This tax advantage is generally disliked by the seller, who has to pay taxes on the gap.

This opposite conveniences scheme between the purchaser and seller has been deliberately introduced by the laws in order to have two different interests on the negotiation of the deal.

In the past, MLBO transactions have been considered as an abusive scheme only aimed at the deduction of interest expenses incurred by the acquisition vehicles against the income of the target.

However, in the last year, both the ITO and the Italian courts have changed their approach by taking the view that combinations have to be seen as the natural conclusive phase of MLBO transactions and they are crucial for the repayment of the debt to the lenders.

Italian MLBO cases should go forward by following best practice routes. However, a compliance check following its whole execution is necessary depending on the final assets (e.g. real estate or business). Many cases have become truly international, in particular regarding capital, funding and special purpose vehicles (SPVs). It is therefore of utmost importance to exclude the abusive nature of the MLBO, paying attention to tax compliance on a cross-border structure, which is often utilised for merger and acquisitions operations.

Daniele Carlo Trivi |

|

|---|---|

|

Equity partner Belluzzo International PartnersTel: +39 02 365 69657 Daniel Trivi is an equity partner of Belluzzo International Partners since 2016. Previously, he worked up to partner level in a tax department of a primary auditing company and then as a partner managing the tax division in a primary Italian law firm. Daniel acquired, through a long professional career, extensive experience in international taxation, business structuring and group reorganisation, banking, finance and capital market taxation and regulation, tax litigation and international cross-border transactions. He advises domestic and multinational companies, banks, financial entities and he is also regularly a part of major cross-border and securitisation transactions. He holds a degree in business administration (Bocconi University, Milan) and has regularly participated as a panellist in several courses, seminars and workshops, as well as publishing contributions in Italian and international specialised magazines. |

Luigi Belluzzo |

|

|---|---|

|

Managing partner Belluzzo International PartnersTel: +39 02 365 69657 Luigi Belluzzo joined Belluzzo in 1994, after having benefited from relevant experience in the UK, and is now the managing partner of the firm. His expertise includes planning for high-net-worth individuals, trusts and family office, with a strong emphasis on both domestic and international planning, governance and inheritance issues. Corporate reorganisation, tax litigation, structured finance and M&A complete his background as a commercialista and TEP (trust and estate practitioner). Luigi is a professor at SDA Bocconi University and is a regular speaker at Il Sole 24 Ore. He has published a significant number of works including the 'Italian Guide on Estate Planning' for Il Sole 24 Ore. He is the chair of the Italian Branch of STEP-Advising Families Across Generations, a member of IFA (International Fiscal Association) and the country correspondent for Italy for the publication Trusts&Trustees, Oxford University Press. |