A non-resident financial entity interested in setting up a banking or similar operation in Brazil should strongly consider all alternative routes before entering the market, instead of just simply opting for a traditional commercial bank model.

In this article, the development of Brazil's fintech boom is explored, taking account of how its remarkable operational, regulatory and tax benefits have transformed the financial landscape.

The fintech skyrocket in Brazil

Brazil is the country with the largest number of fintechs in Latin America. According to a study released by Radar FintechLab, at the end of the first half of 2019, Brazil had a total of 604 financial start-ups in operation, which represented a growth of 33% in comparison to the first half of 2018. These numbers show that the Brazilian market remains intrigued about the potential of this area and explains the correlated growth in the fintech market.

Among the start-ups mapped by Radar FintechLab, emerging businesses were identified as active across several market segments such as insurance, cryptocurrencies and distributed ledger technology (DTL), investments, funding, digital banks and payments among other sectors.

Another survey run by Finnovation, in collaboration with Finnovista and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), considered other Latin American countries that stand out for their fintech infrastructure of conceiving data of great relevance to the market. The research revealed that Mexico was in second place, behind Brazil, with 334 active fintech start-ups, followed by Colombia with 180, Argentina with 116 and Chile with 84.

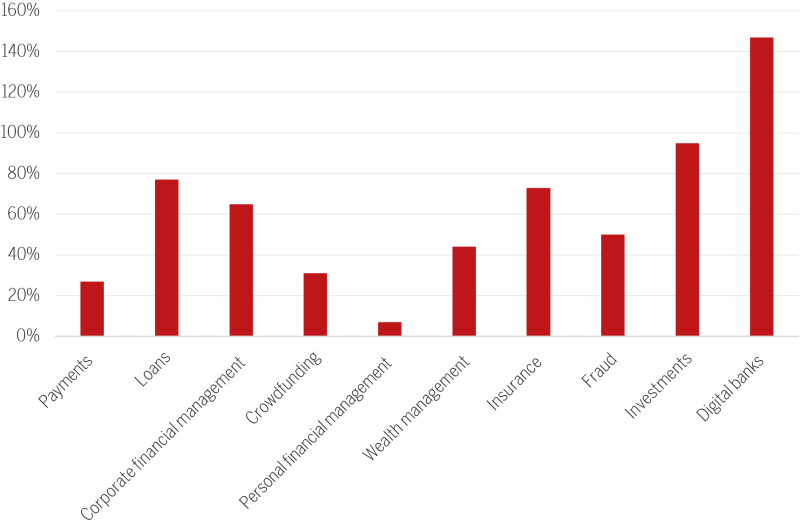

The absolute numbers by segment produced similar results to the study elaborated by Radar FintechLab. It revealed that the Brazilian fintechs operating in the loan sector represent the third biggest slice of this market, at a rate equivalent to 15% of the total analysed start-ups. An important figure for the purposes of the market study was the indicator of annual growth per segment of operation (see Figure 1).

To enhance the market performance data previously mentioned, the table shows that the loans and insurances segments have respectively the third and fourth highest rates of growth among all analysed segments.

Figure 1: Annual growth/segment

Source: 2018 Fintech Radar Brazil study

What is a fintech?

Despite the growth of the area, the definition of the term remains a prime subject for debate – so, what is a fintech? The term is the combination of the words 'financial' and 'technology', and is often used to designate companies that rely on a business model, distinguished from the traditional banks in regard of their offering of products and financial services, and which instead operate through digital platforms.

Following the global financial crisis in 2008, there was a significant increase in regulations for the financial sector, and this development also prompted the rise of fintechs. Taking advantage of the gap in investments, fintechs started to offer technology at a lower cost and through more flexible transactions. It is also worth noting that many of the people that began to promote the fintech expansion had come from the major financial institutions that were affected by the 2008 crisis.

The accelerated development of this niche area embraces the most varied types of financial services such as: digital banking, crowdfunding, invoices automation, online accounting, insurances, and credit democratisation to small- and medium-sized companies.

Financial competition and the fintech challenge

The challenge launched by fintechs is to provide high quality services through technology, while becoming more agile, convenient and competitively priced than traditional offerings. This rising competition facing the traditional banks can, in the medium term, reduce the huge share held by key players in the banking sector. The Banking Economy Report published annually by the Brazilian Central Bank stated that the banking concentration had reached 80.4% in 2018. In other words, more than three-quarters of all assets and resources from commercial financial institutions in Brazil were held by the five largest banks in the country: Caixa Econômica Federal, Banco do Brasil, Itaú Unibanco, Bradesco and Santander.

However, following the expansion of the fintech sector in Brazil, it is expected that this number will decrease. For instance, Nubank, a neobank that was considered as one of the country's biggest fintech enterprises in 2019, has gathered more than six million consumers across Brazil. In an interview with Consumidor Moderno, the co-founder of Nubank, Cristina Junqueira, explained that the key factor for this growth is mainly due to their provision of more affordable financial products and services.

On the other hand, fintechs have also faced limitations that are often difficult to overcome for small businesses. One of them was simply the difficulty of raising money, the most important starting point for businesses within the financial system. In Brazil, before improvements were made to the regulations, fintechs could not make loans if they were not associated with a financial institution.

Regulations have improved competition in the credit market

In 2018, the National Monetary Council (Conselho Monetário Nacional) approved Resolution No. 4,656/18 and Rule No. 3,898/18, which confirmed the existence of two more types of financial institutions with exclusive formats for granting bank loans through digital platforms. Based on these new regulations, fintechs then started to offer digital credit and to act as direct credit companies (DCC) (Sociedades de Crédito Direto, or SCD) or peer-to-peer (P2P) lending companies (Sociedade de Empréstimo entre Pessoas, or SEP).

The Brazilian Central Bank showed itself to be favourable to technological advances and predicted that these new fintechs would encourage healthy competition with traditional banks. The Brazilian Central Bank predicted that the developments would provide consumers with a differentiated and low-cost experience, in addition to the emergence of new solutions to operate in the financial market.

The DCC is a financial entity with the main purpose of carrying out credit rights loans, financing, and acquisition transactions, which are made exclusively through a digital platform and through financial resources from its own capital. The DCC can also perform other services such as third parties' credit analysis, insurances linked to credit transactions, and even the issuance of electronic currency. A P2P is characterised as a financial institution whose purpose is to carry out financing and loans transactions between individuals or entities exclusively through a digital platform. Therefore, it intermediates the relationship between the creditor and debtor and may charge fees for those services.

Unlike the DCCs, the P2P can raise funds from third parties provided that they are linked to the loan transaction. The conditions for raising funding with unqualified investors are very restrictive so that the P2P is often expected to raise funding mainly with qualified and professional investors. In addition, P2Ps can also provide other services, such as the issuance of electronic currency, credit charge on behalf of its customers, inter alia.

Similar to commercial banks, P2Ps and DCC companies are authorised by the Brazilian Central Bank and can offer credit to legal entities and individuals in multiple ways. They can acquire credit cards and other receivables, can provide working capital, real estate financing, trade financing, and they can also provide financing for capital expenditures. For individuals, in addition to real estate financing and mortgages, they can offer payroll collateralised loans, direct credit to the consumer, and general personal loans.

However, there are some clear downsides to the P2P model when compared to a commercial bank or credit and finance company. P2Ps regularly cannot raise funding through deposits of any type – neither bills nor notes – and can only do so with professional or qualified investors through a direct credit approach, by which the investor fully runs the credit risk. Moreover, commercial banks may also be allowed to have other financial businesses such as foreign exchange trading, whereas the business of P2Ps are more restrictive.

Fintechs have optimised tax and operational costs

As DCC uses its own capital to finance debtors, and P2P usually obtains funding with the assistance of qualified or professional investors, meaning their level of systemic risk is low. Therefore, the compliance with applicable Brazilian Central Bank regulations can be achieved with a well-structured, controlled approach in a less expensive and burdensome manner, in comparison to other business models.

The tax burden of a DCC or P2P is also lower than the burden of a commercial bank or financing company. The chart below summarises the comparative tax burdens of a fintech and other financial businesses.

Bank |

CFC |

DCC and P2P |

|

Income tax |

25.00% |

25.00% |

25.00% |

Social contribution tax |

20.00% |

15.00% |

9.00% |

PIS/COFINS tax |

4.65% |

4.65% |

4.65% |

Deduction of PIS/COFINS tax |

-2.09% |

-1.86% |

-1.58% |

Total tax burden |

47.56% |

42.79% |

37.07% |

The taxes are mostly owed on a monthly basis. It should be assumed that the municipal services tax only applies to financial fees and levies at the same level in all business models.

A commercial bank, for instance, must pay federal corporate income taxes of 45% over their profits, including 25% of income tax and 20% of social contribution tax. The bank also has to pay 4.65% of federal turnover taxes on its financial margin (PIS/COFINS tax) which are deductible from the corporate income taxes. In total, the bank pays taxes overall on an effective rate of 47.56% over its financial margin.

The credit and finance company has to pay around 25% income tax, 15% social contribution tax and 4.65% PIS/COFINS tax ending up with an effective tax burden of around 42.79%, whereas a DCC and P2P pay 34% corporate income taxes plus 4.65% PIS/COFINS with a total tax burden of 37.07%.

On this basis, the fintechs spare 10% of their total profit margin in taxes, when compared with banks, and almost 6% when compared with other financial businesses. However, there are further tax advantages.

A non-resident, for instance, willing to extend credit to Brazilian entities and individuals can open a local financial account under Resolution No. 4,373/14 and through this account may invest in a local private credit fund (Fundo Investimento em Direito Creditório, or FIDC). This, in turn, may act as a professional investor and purchase credit originated by financial entities or may provide direct funding for credit offered by P2P. The investor may have a commercial partnership with the P2P to extend credit and may even have a credit consulting company of its own, effectively verifying and approving the credit model and the debtors. The FIDC, for its turn, is not subject to taxation in its portfolio on a monthly basis but is rather subject to 15% taxation on the redemption of quotas for non-residents not located in low tax jurisdictions.

A Brazilian resident, who is a qualified or professional investor, may also use a closed ended FIDC to extend funding in the credit sector with a similar taxation ranging from 15% to 22.5% on the amortisation of the quotas.

In the FIDC, all expenses and costs are tax deductible in the tax computation. Meanwhile, in the financial business itself, the deduction of several significant expenses is limited in time and subject to several conditions. One important example is the provision for credit recovery, which is not deductible for corporate income taxes until such time when the legislation believes that the loss is effectively realised and the tax authorities challenge the deduction of such provision also in the PIS/COFINS tax basis.

Conclusion

Even when considering that fintechs may have a restricted scope of operation when compared to the traditionally wide-ranging services of a bank or credit and finance company, the benefits are slowly beginning to shine bright.

Fintechs can gain funding from a couple of professional or qualified investors, partner up with the FIDCs, and end up operating a modern and high-tech business model. It also turns out to be the best alternative considering the operational costs and taxation. Therefore, the numbers of fintech companies continue to grow, and are consolidating themselves as an alternative investment option for investors who seek to enter the Brazilian credit market.

Lavinia Junqueira |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Junqueira Ie Advogados Tel: +55 11 4550 2784 Lavinia Junqueira is a founding partner at Junqueira Ie Advogados. She has more than 20 years of experience as a lawyer, advising financial institutions and companies, while structuring and implementing financial transactions in Brazil and abroad. She acts as senior counsel to Brazilian multinational companies, and has extensive experience with legal, regulatory and tax issues related to the Brazilian financial market. This includes work for the Brazilian Central Bank on foreign exchange regulations, tax and regulatory advice for financial institutions, and assistance to international banks on structuring and setting up their Brazilian operations. |

Cauê Rodrigues |

|

|---|---|

|

Associate Junqueira Ie Advogados Tel: +55 11 4550 3118 Cauê Rodrigues is an associate at Junqueira Ie Advogados. He has previously worked in renowned law firms in São Paulo, international banks and multinational companies as a tax consultant. He advises financial institutions and companies, while structuring and implementing financial transactions in Brazil and abroad, including on regulatory, accounting and tax issues. He has solid ground expertise on tax matters related to the Brazilian and international capital markets, such as financial institutions, asset managers and placement agents. |