ITR's focus in this issue on diversity and inclusion in the tax profession is a valuable contribution to the ongoing efforts by many groups and individuals to ensure that opportunities in tax are open to all. This is defined in several sources as:

"[R]especting and appreciating what makes…[people]..different, in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, religion, disability, sexual orientation, education, and national origin". [emphasis added]

Most companies have diversity and inclusion goals as a priority, and it is widely argued that this is not just a politically correct fad or something that improves a company's reputation, but creates a competitive advantage as diverse workforces can be more productive, innovative and successful. Diverse teams, with statistical research to support the conclusion, are better at bringing different perspectives, increasing creativity and innovation, providing better and faster problem-solving and decision-making solutions, with more engaged employees resulting in improvements in recruitment and retention.

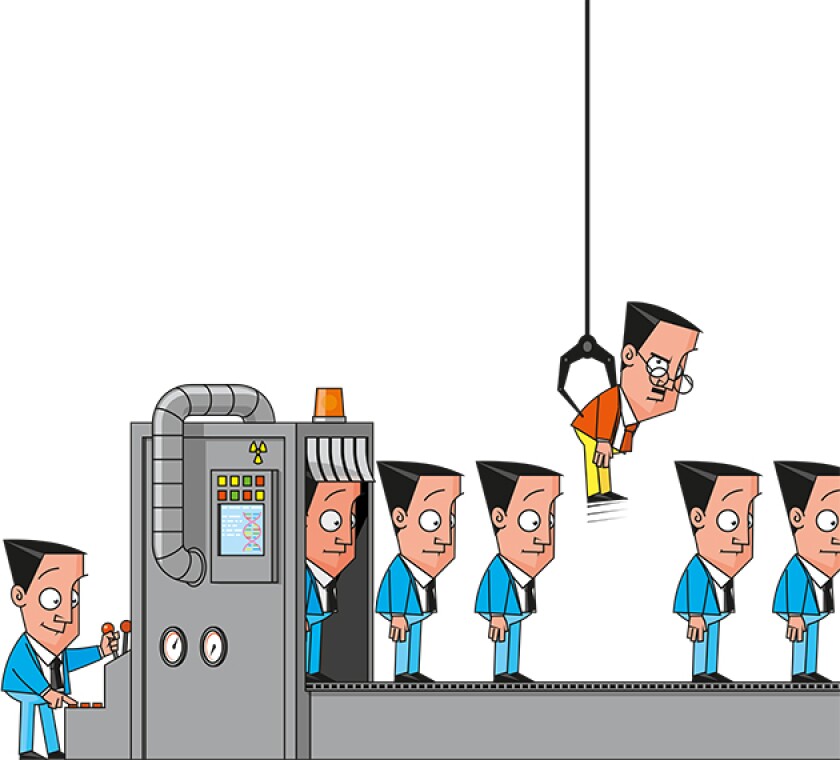

The historic experience, to which diversity and inclusion policies are the response, was that institutional hierarchies, in private and public sectors, tended to recruit, retain and promote those who were 'like us', and discriminated against those who did not share similar life experiences, education, gender, ethnicity and other characteristics.

It is well known that the role of the tax department has changed dramatically over the past several years and will continue to change in the future. The changes have been driven by many external developments:

Public and stakeholder expectations;

Risk appetite and CFO/board visibility of tax;

Increased importance of business/tax understanding and dialogue;

Digitalisation of accounting data and increased use of mechanisation in processes;

Tax administrations increased use of data analytics and associated risks; and

Constant pressure to provide more and better support for the business and CFO with less resources.

As a result of these and other trends, the skills needed in tomorrow's tax department will be different from those valued and rewarded in the past. The traditional, largely technical skills are no longer enough to fulfil all the needs of the modern tax team and we see and hear discussions about the need for 'taxologists', process change managers, trusted business advisers and others with different skills from traditional specialist legal and analytical expertise.

HQ tax teams influence the skills and diversity gaps

Although the need for those skills is recognised, there is a significant difference between identifying the need or desirability for a particular skill and finding the individual with the right experience, expertise and motivation to take on that role within existing tax teams or from external recruitment.

Part of this skills gap could be driven by the headquarters (HQ) tax department (and probably many other parts of the corporate HQ), limiting their search for skills to those who are, in critical ways, 'like us'.

Tax departments and other parts of large organisations may not be making full use of all the potential of the resources that they have through limiting searches for candidates to fulfil new and different roles solely to those who fit existing perceptions of talent pools and career progression. If we acknowledge that the skills needed for some tax department roles are very different from traditional skillsets, why limit the search to those who have progressed within the historic organisation and whose principal skill is in tax law of the parent company jurisdiction and tax accounting?

We have seen tax departments desperately looking for skilled staff as project managers,

trusted business advisers with detailed knowledge and business understanding, skilled and experienced communicators and negotiators, data analytics experts, experts in system development and process changes and experts in transaction mapping and end-to-end process analysis. Those skills may well be found within the wider tax team of the group, in indirect tax and customs experts, in tax staff in other locations, in the 'shadow' tax teams in business operations outside of the tax department, and in accounting and IT teams. However, these skilled individuals are often not considered, or deliberately ignored, because they have not gone through the traditional route of obtaining experience and expertise in tax law and/or accounting in the HQ jurisdiction.

This limitation of diversity and inclusion may be part of an enterprise culture or practice that assumes that only those with home country expertise and experience are capable of taking on lead roles in almost any business activity.

There are many examples of groups that have a strong commitment to diversity, with strategic HR goals to improve representation by reference to gender, ethnicity and disability that are strongly focused on the home country (where the majority of employees are probably based). However, these goals are weaker and less effective for the significant minority of staff based outside the home country.

A group with half of its global employment in its home country could celebrate its success in recruiting and promoting women and those of different ethnicity, both praiseworthy achievements. However, the group could be ignoring the fact that senior management and other critical roles are almost exclusively filled by those from the home country who have followed standardised home-country career development routes so that up to half the potential talent pool is ignored and true diversity and inclusivity is not targeted or achieved.

Of course, integrating an individual from a background outside of the HQ country for corporate tax will need an investment in developing the skills and knowledge of that individual, but past investments in increasing diversity and inclusion were required, and have been very successful.

When looking for specialist IT, process management and other skills in tax departments, there have been many conversations in recent years over whether it is better, or easier, to teach a tax specialist another skill, or to teach tax essentials to a skilled practitioner in another discipline with deep knowledge of the business and who shows an interest in broadening their knowledge and developing their career within the tax department. Assumptions about career progression within tax departments may also need to be re-evaluated as individuals look to pursue their personal objectives in life outside of traditional career patterns, so worrying about what an individual will do next within the tax department becomes less important.

Education, experience and national origin

If diversity and inclusion is intended ultimately to ensure that businesses perform better because they use the varied skills and expertise of those who are not 'like us', then part of the focus should be, in addition to ethnicity, gender, religion, disability, a focus on education, experience and national origin.

As the demands placed on tax departments change rapidly and require many new and different skills, should tax departments not expand their pool of candidates for roles by making a conscious decision to look beyond those who are 'like us' in terms of background and experience? Does 'like us' also mean that responsibility has to be co-located with senior management? There has been discussion over several years about greater remote working and virtual networking, but often a reluctance to combine that with senior responsibility outside of the core HQ team.

Diversity and inclusion in tax has improved significantly over the past few years (at least from the perspective of an elderly white male leading diverse global teams) and undoubtedly it has further to go, with the prime focus being on gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and disability.

However, as the roles required within tax change, there are potential benefits for tax departments in not only embracing diversity and inclusion, but also ensuring that they are not limiting their talent pool through assuming that it should be restricted to those, from all genders and ethnicity that have had a career development 'like us'.

As many of those who might be included in a wider and deeper talent pool will also come from diverse backgrounds, they should help the enterprise succeed through bringing those different perspectives, increased creativity and innovation, as well as better and faster problem solving and decision-making. In short, supplying all the benefits that diversity and inclusion policies are reported to deliver.

While diversity should address "age, gender, ethnicity, religion, disability, sexual orientation", we should also expand the talent pool for the new skills required in the modern tax department. This has to be done by making sure that we do not discriminate against potentially excellent candidates for roles by not also looking to diversify teams based on education, experience and national origin outside of the corporate tax team in the main company headquarters.

Giles Parsons worked as an in-house professional at American multinational Caterpillar for more than 20 years, setting its tax policy and coordinating its tax services. Before that, he spent nearly 10 years at PwC. He is also the the chair of the European direct tax committee at the Tax Executive Institute (TEI). In this column, he draws upon his experience to give his perspective on today’s pressing tax issues, and answer questions from readers. |