On March 6 2020, the Advocate-General (A-G) of the Dutch Supreme Court published its conclusion on a case regarding interest deduction following an acquisition of a Dutch group by a French private equity consortium in 2011. The Court of Appeal had previously found the finance arrangement to constitute abuse of law (fraus legis), ruling in favour of the Dutch tax authorities.

Background

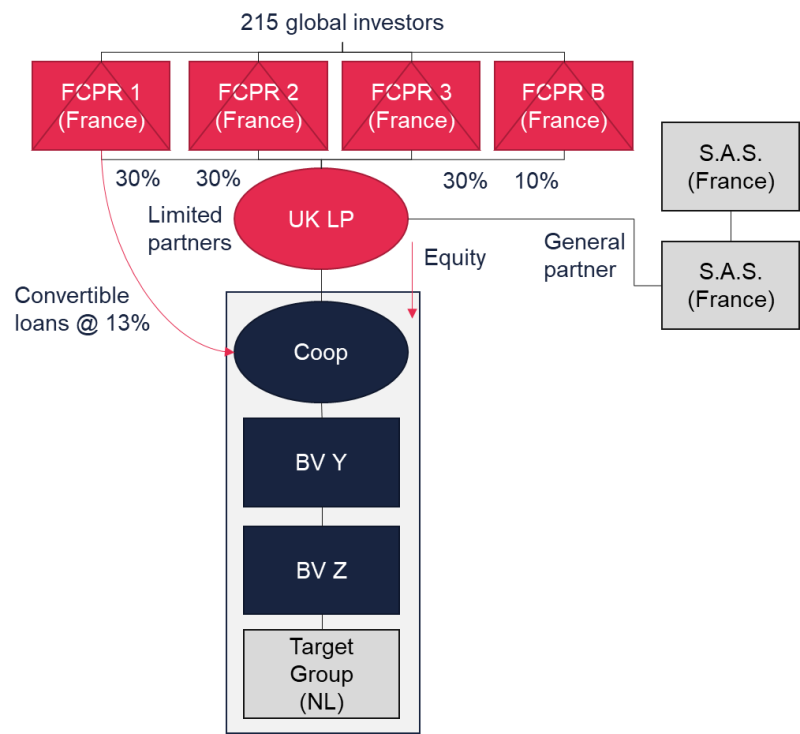

The case concerned a French investment fund that acquired a group of Dutch companies in 2011. To finance the acquisition the investment fund obtained funding from several large group of investors. The collected funds were contributed as a capital investment and were divided among four French fiscally transparent investment vehicles, so-called fonds commun de placement à risque (FCPRs). These four FCPRs were the limited partners of an UK partnership which was transparent for Dutch tax purposes.

In short, a Dutch acquisition vehicle was set up to acquire the shares of the Dutch group. Three of the funds held directly an interest of 30% in the acquisition vehicle and the remaining interest of 10% was held by the fourth fund. The acquisition vehicle received the gathered funds from the FCPRs, partly in the form of convertible instruments with a compounded annual interest rate of 13% and partly in the form of an equity contribution.

Following the acquisition, the acquired Dutch group joined the CIT fiscal unity with the acquisition vehicle. The chosen fund arrangement created a situation in which the fiscal unity's interest expenses could be offset against the Dutch group's profits, whereas the interest income was left untaxed in France due to the hybrid nature of the FCPRs. See below a simplified structure chart.

Requalification to equity instruments

The first question put forward to the A-G, was whether under Dutch law, the convertible instruments should be requalified as an equity instrument rather than a debt instrument. Like in most jurisdictions, under Dutch tax law interest payments on a loan are deductible and payments on equity instruments are non-deductible for tax purposes. In principle, an instrument that qualifies as a loan for Dutch civil law purposes is followed for Dutch tax purposes, unless one of the following three exceptions apply: sham loans, loss financing loans and profit participating loans.

The Dutch tax authorities took the position that the instruments should be characterised as either a so-called sham loan or profit participating loan. The A-G held that as there was a genuine repayment obligation for the debtor, the instruments could therefore not be requalified as a sham loan, a loan that only appears to be a loan while parties intended to provide equity.

An instrument can qualify as a profit participating loan if its interest is profit-dependent, the debt is subordinated to all other creditors, and maturity is either perpetual or 50 years or longer. Considering these formal requirements were not fulfilled, as the interest rate being fixed and the maturity of the loan is 40 years, the A-G agreed with the Court of Appeal that the convertible instruments could not be requalified as a profit participating loan, hereby confirming that even extreme cases cannot justify a less strict interpretation of the relevant criteria.

Arm's-length interest rate

If a debt instrument is not requalified as an equity instrument for Dutch tax purposes, the deduction of interest payments could still be denied insofar the interest rate of the debt instrument itself is not at arm’s-length. At the case at hand, the Court of Appeal accepted the arm’s-length conditions of the debt instrument on the basis of a transfer pricing report provided by the taxpayer.

The A-G believed that the court had adopted an incorrect allocation of the burden of proof and was too quick to rely on the provided transfer pricing report, considering the used comparables are not comparable with the terms and conditions of the convertible instruments. The court's conclusion that the loan was arm's-length was therefore inadequately reasoned according to the A-G.

Anti-base erosion rule

The Dutch tax authorities alternatively challenged the arrangement on the basis of the anti-base erosion interest deduction limitation rule within the meaning of Article 10a of the Dutch Corporate Income Tax Act 1969. The anti-base erosion rule denies the deduction of interest paid by a Dutch corporate taxpayer to a related party insofar the relevant debt is connected with, inter alia, an acquisition of shares in a company, unless predominantly sound business reasons underlie the acquisition and the funding of the acquisition.

The entity that provides the debt instrument is defined as a related party when it holds an interest of a third or more in the debtor, or another party holds an interest of a third or more in the creditor and debtor. Since none of the FCPRs held a sufficiently large interest (a third or more) in the Dutch entity, the A-G found that the denial of interest could not be based on the anti-base erosion rule. The fact that the anti-base erosion rule has been amended as of 2017 with an extension of the definition of related parties by the so-called collaborating group, could not be applied with retrospective affect and therefore not change the meaning of related parties at the time of the underlying transaction (2011).

Abuse of law

Although none of the aforementioned objections stood in the way of the taxpayer's arrangement, both the court and A-G concluded the arrangement to constitute abuse of law (fraus legis). Pursuant to Dutch case law, abuse of law consists of three constituent elements: the arrangement is created with a tax (avoidance) motive, the arrangement is artificial and its outcome is not in line with the object and purpose of the law. The fact that the convertible instruments were provided by formally separate FCPRs that were not subject to tax for the interest on the convertible instruments, being arranged in such a way to avoid applicability of Dutch interest-deduction rules (i.e. criteria of related parties) and thus realising a tax advantage, caused the structure to be both artificial and set up with a tax avoidance motive.

The third requirement for abuse of law, that the outcome of the arrangement is not in line with the object and purpose of the law, was satisfied inter alia because the reasons underlying the loans were not commercial but tax-oriented. If the anti-base erosion rule had not been avoided by way of these apparently meaningless intermediate steps, the interest-deduction would have been denied. This outcome should likewise be appropriate in the present situation, according to the A-G.

Takeaway

Although the Dutch Supreme Court often follows the advice of the A-G, it has been reluctant in the past to restrict companies in their choice how to finance their business investments (either in the form of debt or equity). Considering the anti-base erosion rule has been adapted in 2017 to include situations such as the one at hand, where companies with sufficiently small shares in the debtor together form a collaborating group, interest-deduction would be denied in similar situations on the basis of the anti-base erosion (unless the rebuttal scheme is successfully invoked).

The main takeaway of the case at hand is that funds’ acquisition structures require careful tax planning considerations and should be based on sufficient commercial reasons while being substantiated with proper transfer pricing documentation.

Roderik Bouwman

T: +31 20 541 9894

E: roderik.bouwman@dlapiper.com

Gabriël van Gelder

T: +31 20 541 9606