Introduction

The 2022 Tax Law Reform Package in Mexico, effective January 1 2022, brought changes to transfer pricing (TP) obligations for Mexican taxpayers and had a widespread impact well beyond expectations. While some obligations remained unchanged, others now require more in-depth information, an approach that may seem rather forward for a tax authority, especially in the lens of multinational groups with TP obligations in other jurisdictions.

Along with the changes in tax law compliance, particularly for participants in the automotive industry, the supply chain crisis of the past several years intensifies the challenges these companies face.

Distortions to the supply chain impact a company’s financial information, mainly at an operating level. This creates a need for comparability adjustments to maintain the standards required for a reliable TP analysis, proving the company’s transactions with related parties and its prices, margins, and considerations are agreed upon as if with third parties (the arm’s-length principle).

Background

The TP obligations in Mexico, as stated in the Mexican Income Tax Law (MITL) and with supporting articles and clarifications, are strongly based on the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations (the ‘Guidelines’). The burden of proof is on taxpayers to demonstrate their transactions with foreign and domestic related parties are at arm’s length.

This burden of proof is present in the shape of reports and informative returns filed by taxpayers before the Mexican competent tax authority (MCTA) during the calendar year immediately after the reporting fiscal year, as applicable.

Companies operating under the maquiladora regime, which provides tax benefits for these taxpayers, have additional compliance obligations.

The 2022 MITL Reform expanded the TP obligations for taxpayers and clarified items that had been assumed without being included in law. While the modifications are extensive, key changes include:

The limitation of the financial information period for TP analyses from a three-year average to a one-versus-one period (see below);

The extension of Appendix 9 of the Multiple Informative Return (Declaración Informativa Múltiple, or DIM) to include domestic related parties (the pre-reform obligation was limited to foreign related partiegs);

The shortening of deadlines for filing returns; and

Clarification that all results must be within an interquartile range of comparable observations.

Supply chain repercussions on the automotive industry

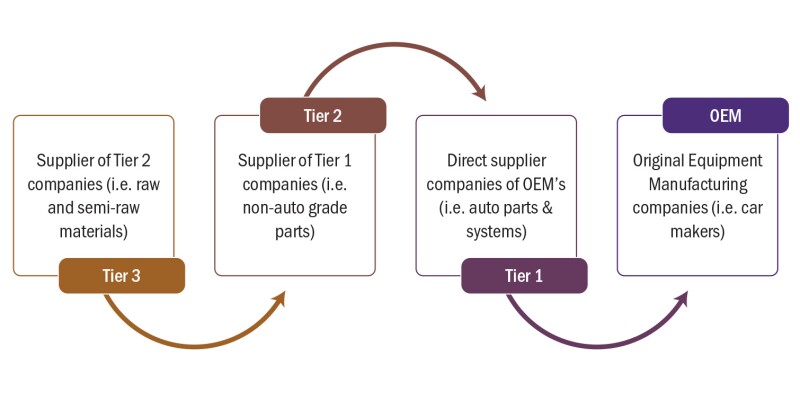

Entities participating in the automotive industry are organised into four main categories, based on their location within the highly integrated supply chain, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Automotive industry supply chain

Source: Elaborated by Deloitte

In Mexico, maquiladoras are cost centres that have as their main operating activity the manufacture and assembly of products sold exclusively to principal foreign related parties. Within the supply chain, maquiladoras are classified as Tier 1 or Tier 2.

The latest supply chain crisis, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, caused a downturn for the automotive sector. Companies and local governments have hence been obliged to identify and manage the resulting risks, including those indirectly affecting supply chains.

For example, COVID-19, the semiconductors global shortage, the Ukraine–Russia conflict, the slowdown in large economies, and a global trend towards increased inflation have destabilised the continuity of the automotive supply chain and affected the manufacture and sale of motor vehicles (EMIS (2022), The Road Ahead: Forces Shaping the Automotive Sector’s 2022 Outlook).

For the automotive industry, the semiconductors shortage crisis paralysed the production of vehicles and auto components by delaying or cancelling production orders and initially causing a work-in-progress (WIP) inventory surplus, or decelerating manufacturing activity because of a shortage in raw materials inventory and reducing average finished product inventory levels.

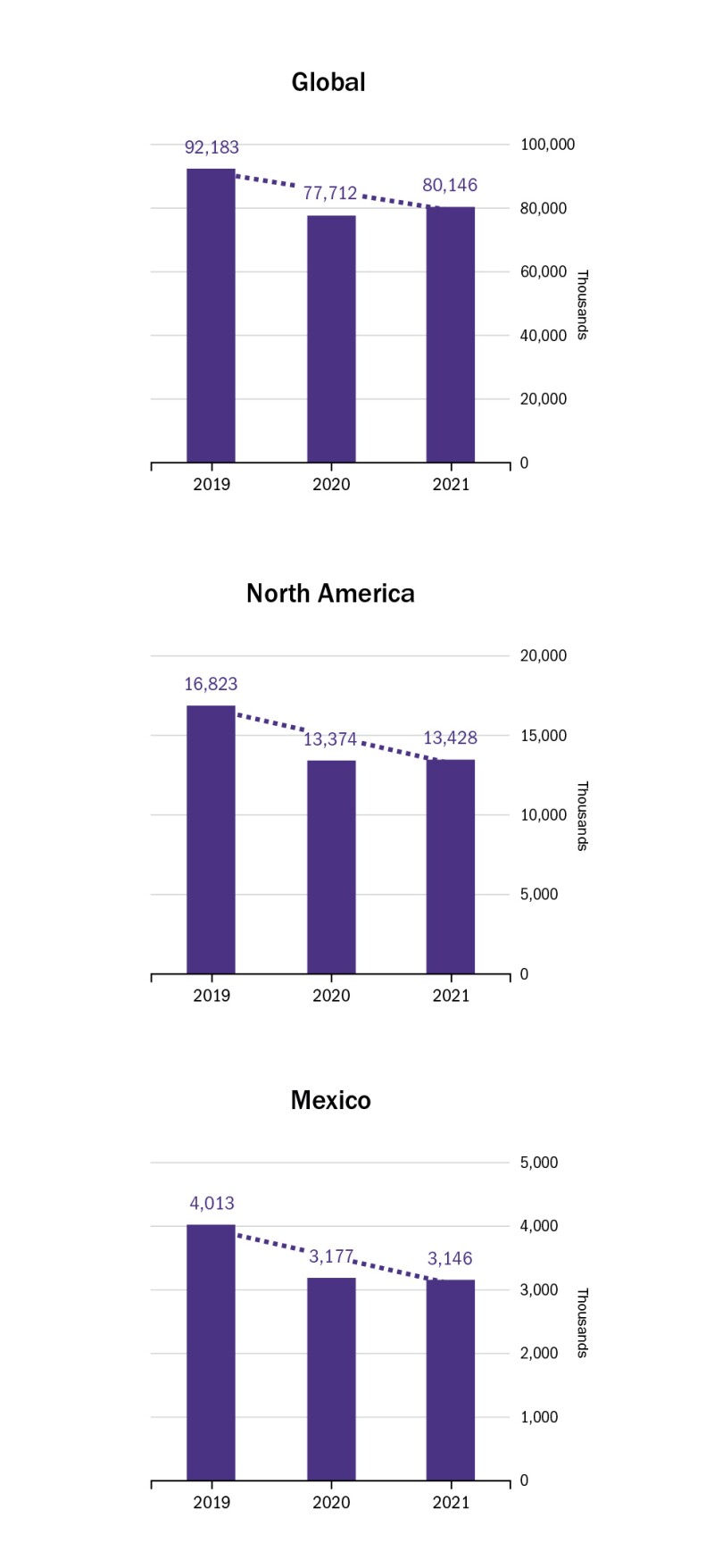

According to the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers (OICA), the global production of motor vehicles decreased by 13% during 2019–21, as shown in Figure 2. For 2021, a slight recovery was recorded, with a 3% increase compared with 2020. In North America, the decrease in vehicle production was 20% for 2019–21, with no recovery path in 2021.

In Mexico, for the same period, the decrease in vehicle production reached 22%. Unlike the behaviour of the global automotive industry, and much like the North American market, the production decrease in 2021 is estimated at 1% in comparison with 2020 (OICA, 2022).

Figure 2: Motor vehicle production units by region (2019-2021)

Source: Elaborated by Deloitte with information from OICA, 2022

Various governments implemented supportive actions to lessen the effects of these distortions. An example is the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act granted by the US government to companies affected by the pandemic, consisting of grants, tax provisions, and other programmes.

In Mexico, any federal government’s financial aid stimuli related to the onset of the pandemic was directed to the general population (e.g., gifting groceries, and tandas, or rotating savings and credit associations), and not so much to well-established companies. The instances where companies received stimuli similar to those offered by the US or other countries were scarce, if not non-existent.

Furthermore, the automotive industry was declared as non-essential in March 2020, halting production until May 2020, when it was declared essential and allowed to resume production.

The decrease in production, the increase in costs, a shortage of inventory, and circumstantial government aid, among other factors, directly impact a company’s financial information, with variations in its income; cost of goods sold (COGS); and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses; as well as balance sheet items. These do not necessarily reflect what the company’s financial reports would be in a normal scenario.

Basis for comparability adjustments

Mindful of the repercussions for a company’s financial information caused by distortions to the supply chain, TP analyses should factor in countermeasures for them to result in reliable conclusions. Chapters I–III of the Guidelines and the OECD guidance on the transfer pricing implications of the COVID-19 pandemic offer a foundation to justify adjustments for unusual results in a distorted framework, particularly when the risks assumed by companies differ in manners that affect the reliability of the results.

In the Mexican framework, post-reform regulations clarify that taxpayers must include a breakdown of adjustments used to eliminate differences in comparable companies. Additionally, TP analyses must compare the tested party’s information for the respective fiscal year with comparable companies’ one-year results (one versus one). The pre-reform customary approach was a three-year average for comparable companies. However, a multi-year average is still applicable if the tested party’s business/product cycle is proved to exceed the one-year mark.

Distortions, their effect on financial information, and reasonable adjustments

Comparability adjustments are applicable only when they enable increased comparability in the analysis. Since the discussed distortions materially affect the conditions being examined, it is reasonable to conclude that the situation grants the possibility of using comparability adjustments.

Generally, comparability adjustments for TP analyses can be classified into two categories:

Adjustments to the tested party; and

Adjustments to comparable observations.

Some adjustments applicable to the tested party and comparable companies include:

Accounting adjustments;

Capital adjustments; and

Adjustments for extraordinary expenses.

Accounting adjustments seek to reduce the discrepancies between accounting standards, which indirectly mitigates the effects of economic distortions (for example, standardisation of deferred taxes records).

Capital adjustments are applicable when differences in functions assumed or market conditions cause discrepancies between the capital intensity of comparable companies and the tested party (for example, maintaining a larger inventory, financing from suppliers, and commercial credits to customers).

Moreover, adjustments for extraordinary expenses are applicable when similar expense levels are not recorded by the tested party or comparable companies. Extraordinary expenses lower the operating profit, which generates differences in profit margins, given that the expenses are unrelated to income received by the company. For an adequate comparability analysis, the exclusion of the expenses must prove that they were circumstantial to the disruption.

For Mexican tested parties, expenses may be excluded only when the requirements of the Mexican financial reporting standards (MFRS) are met.

Another common adjustment to the tested party is the adjustment for idle capacity, which becomes relevant if, during the analysed period, the tested party maintained fixed asset levels lower than those of comparable observations. A greater idle capacity implies a decrease in operating profit by registering an excess in expenses for the maintenance of under-utilised fixed assets.

Adjustments that can be applied to comparable observations include:

Adjustments for incentives or fiscal/economic stimuli; and

Industry-level adjustments.

Adjustments for incentives or stimuli suggest excluding from the comparable companies’ financial information the amounts for said concepts, leveraging the differences of the comparable observations with the tested party, only if the tested party did not receive a similar compensation.

Additionally, the application of an industry adjustment suggests an exhaustive review of an industry’s market conditions. This will allow the definition of minimum comparability conditions, shaping the selection of comparable observations. Therefore, it is essential that functional analyses include general industry characteristics that allow establishing a reference through the evaluation of diagnostic ratios (for example, fixed/total assets, research and development (R&D)/sales, and COGS/sales).

As examples, Ford Motor Company reported in its 2021 annual report significantly lower total net receivables, in comparison with 2020, primarily due to decreasing accounts from wholesale distributors caused by lower inventory purchases. In contrast, General Motors Company, according to its 2021 annual report, experienced an impact to its inventory volumes due to the shortage of semiconductors, which was offset by the implementation of business strategies prioritising the use of semiconductors for vehicles with the highest demand and popularity.

For both OEM examples, financial information, facts, and circumstances must be evaluated in the selection criteria of comparable companies, with special considerations to business strategies implemented (or not), inventory levels, and their effect on income statement results.

Up to this point, adjustment options and discussions have been limited to manufacturers participating in the automotive industry supply chain in Mexico. Options are limited and the conditions to make use of those options are extensive and thorough. However, there is an additional entity within Mexico’s automotive industry that has TP as the very essence of its functions: maquiladoras.

Until 2022, TP compliance for maquiladora activity in Mexico was limited to two modalities:

Safe harbour rules; and

Advance pricing agreements (APAs).

As for comparability adjustment options under those modalities, there is only one, as allowed by the MCTA: idle capacity, with a 20% cap for those in open APA processes and uncapped for those under safe harbour rules.

Final remarks

Uncertainty and inconstancy are conditions that prevail in a real-world context, where the global economy will continuously be affected by phenomena. With globalised supply chains, the micro and macroeconomic environment in Mexico will continue to suffer distortions. Although Mexico cannot do much to control these factors, policies and relevant regulations must focus on leveraging impact to reduce uncertainty.

According to the Mexican TP regulations, in the case of economic distortions, although there are no restrictions for comparability adjustments applicable to the tested party or comparable companies, the MCTA is more comfortable with adjusting the tested party’s information, rather than that of comparable companies.

In the likelihood of a review, the MCTA has a form over substance approach, where underlying circumstances are deprioritised, preferring a formality in financial information and transactions. Each transaction must comply with all requirements (depending on the type of transaction, as classified by law), regardless of background circumstances that affect how the transaction should be analysed.

It is imperative to consider that, while all adjustments could be considered well founded, they need to be based on reasonable and ascertainable supporting documentation that justifies their use. The MCTA could consider photographs, ex ante and ex post production orders, and inventory levels within TP documentation as evidence.

The key point is consistency between facts and circumstances, documentation, and all relevant information. This requires the coordination of relevant departments, such as the production and finance (cost) areas, to adequately support the adjustments. The effort may often prove more work than it is worth, going beyond the reasonability of records kept by taxpayers. One strategy is to consider confirmatory approaches to augment the reasonability of the adjustments.

The changes in the Mexican TP regulations, such as the shortening of the period of information considered and the requirement to strongly back up and break down comparability adjustments, does not offer support to leverage any distortions to a company’s information over a year, therefore stemming the need for stronger comparability adjustments to counter biased information.

TP advisers must stay alert to fluctuations in the global markets and their effects on businesses, as well as changing regulations, to offer the best possible analysis and advise to companies, without compromising results with biased information.