The diversity of intellectual property (IP) protection and healthcare cost management practices across major jurisdictions gives rise to the curious case of parallel imports of prescription drugs. This article explains the transfer pricing implications of parallel imports in the life sciences industry and analyses a landmark court case involving parallel imports.

Supply chain management

Unlike many other industries, the diversity of local regulations prevents life sciences companies from having full control of their resale prices. The prices are determined through separate negotiations in each jurisdiction. Even in a highly integrated economic region such as the EU, it is common for the same prescription drug to be sold at different prices in different jurisdictions.

Independent traders take advantage of the resulting price arbitrage by purchasing prescription drugs from lower-price jurisdictions and resell into higher-price jurisdictions. These are called parallel imports because these unrelated importers operate ‘in parallel’ to the local distribution structure of the original manufacturer of the drugs.

In many jurisdictions, parallel imports are completely legal as a consequence of regulatory measures that aim to reduce healthcare costs by allowing parallel imports to promote competition. In certain countries – the US, for instance – parallel imports are permitted specifically for certain pharmaceutical products under certain conditions, even though the country otherwise follows a regime of national exhaustion of IP rights that gives patent or trademark owners the right to exclude parallel imports.

In the EU, rules provide for a regional protection of IP rights whereby goods circulate freely within the trading union, but parallel imports are banned from non-member countries. However, there have been legal disputes at the European Court of Justice (ECJ) about the permissibility of parallel trade.

Life sciences companies try to ban parallel imports because of the reduced profit margins for them, arguing that, as holders of trademark rights, they should be able to prevent the (mis)use of their trademark rights by parallel importers. Parallel importers conversely allude to freedom of competition and claim that the pharmaceutical company’s primary intent to suppress parallel trade is driven by anti-competitive motives rather than valid trademark concerns.

Free-rider (externality) issue

As the parallel imports are substantially the same as the local products, a parallel importer benefits from the local sales and marketing efforts of the local distributor of the original manufacturer. In the life sciences industry, sales and marketing conducted by the local distributor of a prescription drug manufacturer is mostly directed at doctors prescribing the drug. However, the product sale is made to the pharmaceutical wholesaler/pharmacist.

The consumer can, or in some cases is forced by regulations to, purchase the lower-priced parallel imports. As such, the sales and marketing efforts of the local distribution company end up benefiting the parallel importer and, indirectly, the manufacturer (or its other distributors) that supplied the product to the parallel importer.

This raises an interesting transfer pricing question of whether and, if so, how the manufacturer or its other distributors should compensate the local distributor for its sales and marketing effects from which they derive an indirect benefit through parallel imports.

In the following, the transfer pricing aspects of parallel imports are first discussed from a general OECD perspective. A recent ruling by a German regional tax court on a case of parallel imports is summarised thereafter, highlighting the points to be considered in such situations.

TP implications of parallel trade

From an economic perspective, the marketing activities of the local distributor create externalities directly for the parallel importer and indirectly for the supplier of the parallel importer (which would be the manufacturer or another one of its distributors). The parallel importers and their suppliers can free ride on these efforts and the local distributor cannot prevent them from doing so.

The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations neither mention the term externality nor provide any guidance that explicitly alludes to situations where externalities are present. They can thus only be analysed based on basic transfer pricing principles, taking into account what independent third parties would do when dealing at arm’s length, given the options realistically available to them. This would depend on the facts of the case.

As mentioned before, the parallel imports are neither in the interest of the manufacturer nor of the local distributor. Given that, it seems questionable whether additional compensation can be demanded or enforced by the local distributor against the producer. In a common set-up with the producer being the entrepreneur and the distributor being a routine entity, the distributor would likely not be in a strong bargaining position against the producer given the limited options realistically available to the local distributor.

However, when setting up the distribution arrangement, the distributor would anticipate that parallel imports would eventually lead to lower sales. With the prospect of perhaps even suffering losses, the distributor would not be willing to enter such an agreement and hence some form of compensation would need to be factored in. This could be done, for example, implicitly by granting a higher return for sales made by the distributor or explicitly by covering unsuccessful marketing costs (those leading only to sales by the parallel importer).

It seems clear that the third-party parallel importers, in the lack of any obligation to do so, would not be willing to compensate the distributor in any form.

The following German case illustrates these effects at play.

German court decision

In its ruling dated July 20 2021 (1 K 1388/19), the Nuremberg regional tax court decided on a case concerning the effect of parallel imports on transfer prices. Specifically, the ruling concerns the question of whether marketing services provided by a domestic distributor belonging to a group, which not only benefit its own group but also third-party parallel importers, constitute a hidden profit distribution if the marketing services for the parallel importers are not remunerated separately.

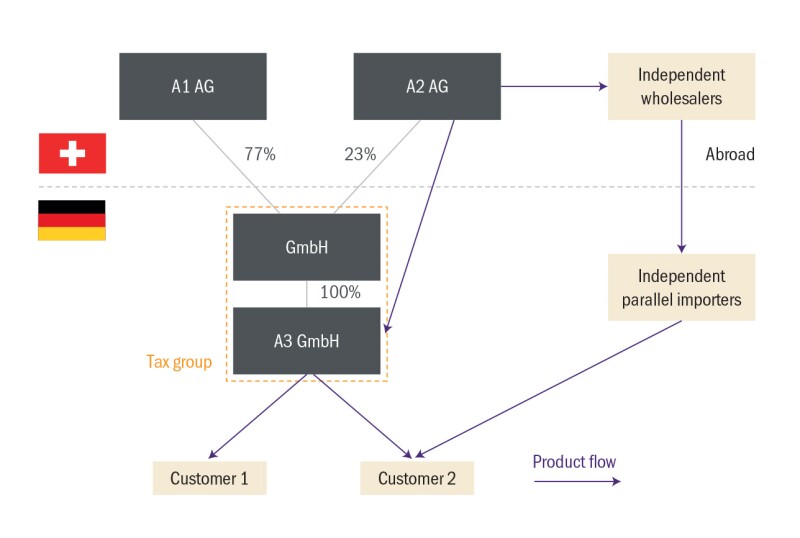

The ruling of the Nuremberg regional tax court was based on the following fact pattern (see also Figure 1). The years 2006–10 were in dispute. The German A3 GmbH promotes and sells products of the foreign group A on the German market. As mentioned above, due to non-tax regulations, the customers of the products are obliged to purchase a part of the products not from A3 GmbH, but more favourably from parallel importers. A3 GmbH receives a remuneration from A2 AG for its own sales in the amount of between 6 and 6.5%. Based on a distribution benchmark, this can be considered arm’s length (margin lies above the median).

Figure 1

There is no separate remuneration of A3 GmbH for expenses/efforts that may have led to sales by parallel importers. However, the bonus payments of A3 GmbH for its sales representatives take into account the sales from parallel imports on a pro rata basis.

A3 GmbH appealed (unsuccessfully) against the amended tax assessments issued by the tax office as a result of the tax audit. In October 2019, A3 GmbH finally took legal action, requesting that the hidden profit distribution be cancelled due to the non-remuneration of marketing activities in connection with parallel imports. The action was successful, as the Nuremberg regional tax court did not consider the requirements for a hidden profit distribution in connection with the parallel imports to be met.

A3 GmbH has suffered a reduction in assets because of bonus payments made to its employees, which also take into account the sales from parallel imports. However, A3 GmbH incurred the marketing expenses in its own interest.

There was no prevented increase in assets since the marketing expenses of A3 GmbH were incurred to persuade customers to purchase A-products and thus to generate its own sales. The fact that parallel importers may also have profited from these efforts was merely an indirect consequence of these efforts and was neither intended nor prevented by A3 GmbH.

The parallel imports were also not in the interest of the foreign parent company, as it could only (indirectly) sell to the parallel importers at a lower price, and it cannot be assumed that this price effect was overcompensated by an opposing quantity effect. Due to the higher profit margin, the parent company would rather have had an interest in domestic sales being made via A3 GmbH, not via the parallel importers. However, due to the European fundamental freedoms, which are supported by repeated decisions of the European Commission and the ECJ, the parent company cannot prevent parallel imports in the EU.

The inclusion of parallel imports in the remuneration of the sales representatives of A3 GmbH is irrelevant, as this remuneration is primarily intended to induce the prescription of A-products, irrespective of whether the supply is made by A3 GmbH or by parallel importers. The remuneration paid to A3 GmbH, on the other hand, is intended to compensate for its own sales performance.

The sales losses of A3 GmbH caused by the parallel imports were therefore not caused by the corporate relationship and consequently do not constitute a reduction of assets in the sense of a hidden profit distribution. There was no contractual or legal basis for A3 GmbH to be entitled to a higher or additional remuneration for parallel imported products. Such an obligation did not exist vis-à-vis the parallel importers, but also not vis-à-vis the parent company. Third parties in the situation of A3 GmbH would not have had a strong negotiating position in this respect either. Rather, the sales losses of A3 GmbH were caused by external third parties (parallel importers).

Lack of evidence

The Nuremberg regional tax court also noted that there was a lack of evidence from the tax office that it was customary in the industry for A3 GmbH to demand remuneration from the parent company for the parallel imports. Furthermore, the court did not consider the assessment of the amount of the hidden profit distribution to be proven.

Firstly, there was no evidence that the undisputed arm’s-length margin of A3 GmbH – which, as mentioned, was above the median – did not at least implicitly take into account the effects on earnings from the parallel imports. Rather, it would even have been agreed during the tax audit that the margins achieved of between 6 and 6.5% of net sales were at arm’s length.

Secondly, the publicly available market studies used by the tax audit, since they were privately financed and thus objectivity could not be ensured, were considered to have only a very low or irrelevant probative value.

Thirdly, the tax office had used findings that had not been made public. In so far as findings from other tax audits were used by the tax authorities – which were not disclosed, even at the request of A3 GmbH with reference to tax secrecy – the necessary evidence regarding the amount of the assumed hidden profit distribution was deemed not to have been provided.

The Nuremberg regional tax court allowed an appeal to the Federal Fiscal Court (Bundesfinanzhof, or BFH) because this would be a ruling on an unresolved legal issue of economic significance. The case is pending before the BFH under file number I R 41/21.

Summary

Parallel trade is a phenomenon resulting from the interplay of internationally differing IP protection regimes and cost management efforts to reduce healthcare spend. In the absence of clear transfer pricing guidance regarding how to deal with its consequences, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Hence, a thorough case-specific analysis is warranted, and solid documentation of such analysis is key to being able to support the transfer pricing set-up when challenged by the tax authorities.