The drive to recruit and retain talent, and the easing of border restrictions, has driven a dramatic increase in flexible working policies in financial institutions. This article explores various transfer pricing considerations associated with remote working models, including specific challenges arising in the banking, capital markets, and fintech sectors.

The demand for flexible working options did not start with COVID-19, but it certainly accelerated as a result of it. Working from home has become a new normal. Long after the pandemic ends, some employees will want to continue to work away from the office, whether at home or in other jurisdictions.

Given the challenges in retaining talent, where flexibility is one of the highest priorities for employees, and the potential long-term savings in overheads, coupled with the need to attract niche talent no matter the location, organisations may be just as enthusiastic to continue flexible working policies. This places a significant burden on support functions such as tax, legal, IT, and regulatory affairs to provide that flexibility but at the same time manage business risk within appropriate limits.

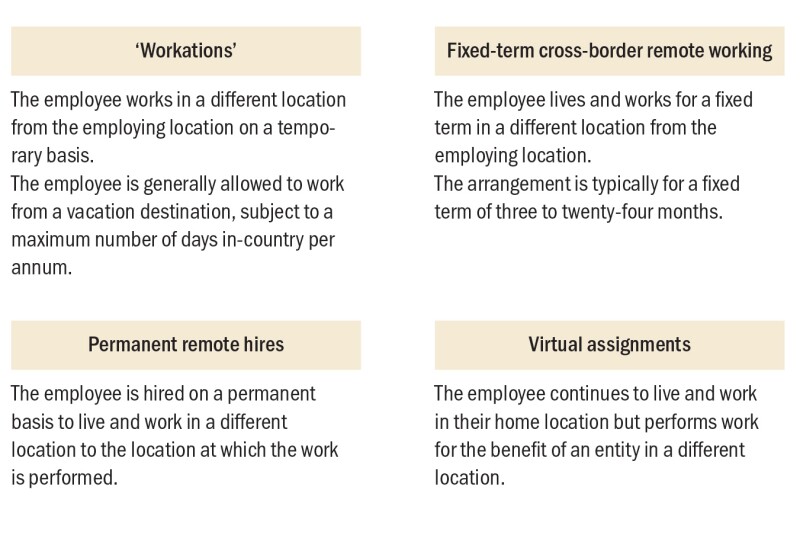

There is a wide range of flexible working options made available by organisations to employees, and the trend for flexible working arrangements has increased the demand for cross-border flexibility. Outlined in Table 1 are some examples that may expose organisations to transfer pricing or other tax risks.

Table 1

The success of remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that businesses can continue even with flexible working arrangements. What is not certain is the approach that tax authorities may take. We have already seen a focus by some tax authorities on the treatment for dislocated individuals during the pandemic, and as flexible work arrangements grow in popularity, further focus may be needed in this area.

Remote working and taxable presence

The first question to answer is around taxable presence. Groups should first determine whether the flexible remote working arrangements give rise to a local taxable presence under domestic law (for example, a permanent establishment or under source-based taxation). To the extent that there is a relevant double tax treaty (DTT), the DTT may limit the taxable presence.

Under the OECD Model Tax Convention, there are two types of permanent establishments:

Fixed place of business through which the business of the enterprise is wholly or partly carried on; and

A dependent agency where an agent acting on behalf of the enterprise has, and habitually exercises their, authority to do business on behalf of the enterprise.

Remote working arrangements that are less than six months in duration for all employees of an enterprise in aggregate for that location are less likely to create a permanent establishment due to the lack of permanence. However, this can vary significantly depending on the jurisdiction. Furthermore, care needs to be taken where the individuals are very senior or where there is intense activity over a short period.

Where an employee is offshore working remotely for periods in excess of six months, the question often revolves around whether a ‘home office’ is at the disposal of the business, which is required for there to be a fixed place of business. The OECD Model Commentary on Article 5 (at paragraph 18), suggests that this may indeed be the case where the business requires an individual to work from home and is not providing an office to an employee where the nature of the business clearly requires an office.

Where remote employees negotiate and/or sign contracts (other than for minor activities) in the remote location, then it is likely to create an agency permanent establishment and further consideration of local legislation and the relevant DTTs is required irrespective of the position regarding a fixed place of business permanent establishment.

Emerging issues facing financial institutions

Financial institutions have seen multiple types of remote working practice that have the potential to create corporate tax and transfer pricing risks. The sector is particularly impacted by remote working requests from senior employees and employees with highly specialised skills. Three typical scenarios are presented below that have commonly arisen over the past two years, and the related transfer pricing concerns.

Senior management personnel based in a location other than the headquarters

Senior management personnel who are on long-term assignments (potentially for family or personal reasons) and are employed in an entity in a different location to the headquarters of the multinational organisation may have significant decision-making authority and it may not be commercially possible to curtail the ability of such personnel to negotiate contracts or make key decisions.

In such instances, it is important to note that there is a high degree of interaction between permanent establishment risk and transfer pricing. While each tax risk would need to be considered and analysed discretely, as a practical matter some revenue authorities are less likely to raise agency permanent establishment issues where the authorities are satisfied that the local entity employing the senior management personnel is sufficiently remunerated.

Some revenue authorities have provided explicit guidance on this interaction between permanent establishments and transfer pricing. See, for example, paragraphs 16.2–6.3 of the transfer pricing guidance issued by the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. The guidance notes that no further attribution of profits to an agency permanent establishment of a foreign enterprise is required where the local entity receives remuneration that is commensurate with its functions, assets and risks, and the arm’s-length nature of the remuneration is supported by transfer pricing documentation.

A front-office employee working remotely in a country with an existing bank branch

Banking organisations have a heavy branch footprint globally. Accordingly, where an employee of the enterprise travels to, and works from, the country where there is an existing branch, there is a question of whether profits may be attributed to the branch.

This is particularly the case where an employee habitually visits the branch office for business reasons but, depending on the jurisdiction, may also be a relevant consideration where the employee is making use of the organisation’s ‘workation’ policy.

In the case of front-office employees, their day-to-day work is highly likely to involve significant amounts of client interaction and the development of business opportunities. As such, revenue authorities may expect additional profit attribution to an existing branch for the functions of travelling front-office employees.

With regard to the attribution of profits to branches, an analysis of the key entrepreneurial risk-taking (KERT) functions will be fundamental in determining which part of the enterprise has economic ownership of the financial assets, and therefore should have the attendant risks and rewards. This involves an analysis of where the decision to assume risk when creating a financial asset (such as trade or a loan) was made, as well as where the risks of the financial assets are managed once the assets are on the books of the enterprise.

Tracking the location of the KERT functions may be particularly challenging where there is a high degree of employee movement and the results of a KERT functional analysis from a tax perspective may not always be consistent with existing regulatory permissions for a jurisdiction.

Remote working for a software developer at a fintech

With the development and adaptation of digitalisation, fintechs (as well as traditional financial services organisations) are investing and developing a technology-driven business framework. The novel value chain, combined with the need to attract niche talent from a global pool, presents transfer pricing challenges. Multinational organisations may allow or encourage flexible work policies such as virtual assignments or permanent remote hires in a different location to where the organisation’s research and development (R&D) centre is initially established. However, the need to compete for scarce talent in the market is offset by a need to consider whether intangibles could be attributed to the remote location from a transfer pricing perspective.

The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines have set out a framework to consider the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection, and exploitation (DEMPE) functions in respect of the economic ownership of intangible assets to determine which enterprise within a multinational organisation should earn the intangibles-related return. In practice, however, transfer pricing disputes arise due to the subjectivity in valuing the intangibles-related return, as well as how to split the return amongst multiple enterprises that have performed DEMPE functions.

While cost-plus arrangements have traditionally been used to remunerate development functions performed by sole employees in different locations, this transfer pricing model may come under strain where the performance of DEMPE functions is spread widely and the economic ownership of the IP is highly fragmented, such that there is no clear ‘hub’ to bear the entrepreneurial risk and make the cost-plus payments.

In short, where employees who are lead developers and key decision-makers within the technology development process are located in different jurisdictions, special consideration will be needed in designing a transfer pricing policy that is fit for purpose. This involves being sufficiently flexible to accommodate business growth and changes, as well as having regard to the post-BEPS principles of aligning value creation with substance.

Managing TP with flexible remote working arrangements

Flexible remote working is a feature of almost all conversations about recruiting and retaining talent in financial services. Multi-jurisdictional client-facing teams and other virtual teams spreading across borders will almost certainly result in tax considerations and a requirement to re-align the attribution of profits between legal entities and branches.

The financial services sector is set up to manage such a change, because, in general, banks already operate revenue or profit split transfer pricing models for most business lines. However, one key challenge with the current models is the KERT functional analysis and transfer pricing model attributing profits at a very precise and narrow level of aggregation – sometimes even to individual deals or single trading books. Shifts of key individuals to other jurisdictions could entirely shift the attribution of profit for such transfer pricing models.

As business working becomes increasingly multi-jurisdictional and cross-border teaming and collaboration is encouraged, multinationals may trend towards broader, more aggregated profit splits. This would reflect the factual changes in the business and reduce the complexity of their profit split models from administrative and operational perspectives.

Conclusion

Business perceptions of flexible and remote working policies changed because they supported business continuity. The growing acceptance of the practice has been met by interest from employees across banks and other financial institutions, and is expected to be a key part of recruiting and retaining talent in the industry.

While there is concern about permanent establishment risks arising, most financial institutions already have branches across most geographies, and therefore transfer pricing considerations quickly become the primary issue.

As with all significant business changes involving multiple stakeholders, where flexible work policies are being discussed and implemented, upfront engagement across the business will be important to educate parties on the transfer pricing impacts and allow the development and implementation of controls to flag and address transfer pricing consequences in a timely manner.