BEPS 2.0 is not just a significant development in international taxation, but also a fundamental change in the mechanism by which corporate taxation for international organisations is calculated.

The historical basis for the calculation of corporate income tax was residency or permanent establishment. BEPS 2.0 has now introduced an allocation of profits by markets (pillar one) and a global minimum tax per jurisdiction (pillar two). In addition, the qualified domestic minimum top-up tax (QDMTT) under pillar two allows jurisdictions to introduce a minimum corporate tax rate and therefore maintain a competitive tax regime. These changes shift the calculation mechanism and the data required.

With the start date for BEPS 2.0 generally being deferred to the beginning of 2024, implementation by tax authorities will likely be staggered depending on the jurisdiction, so this only gives companies around 12 months or less to get processes and systems ready. Also, while an organisation may not be subject to paying tax under pillar one or two, it will indirectly still need to calculate QDMTT, applying similar mechanisms as a baseline.

Data is key to avoiding manual work and reconciliations using spreadsheets. From the work EY has done, around 150 to 200 data points are required for BEPS 2.0, spanning financial data, tax data, HR data, and corporate data. In addition, there is a whole range of local variations and elections to manage.

The role of enterprise systems

Notwithstanding, financial reporting systems are a good place to start. These are an organisation’s enterprise system, such as ERP (enterprise resource planning), EPM (enterprise performance management), and other enterprise productivity platforms.

ERP has become the backbone of an organisation’s accounting process, where most of the underlying transactions are recorded or booked. In fact, most organisations have transformation initiatives with a best practice goal of integrating multiple systems into a single ERP. However, most organisations still need to consolidate multiple instances or legacy systems, or simply require a point-in-time cut of data. This is where EPM has increased in popularity.

A recent EY survey of 1,650 global executives found that the C-suite is putting pressure on tax departments to transform and increase their use of technology – 91% of chief financial officers (CFOs) say that they are transforming their tax function.

EPM has traditionally been used for consolidation or financial reporting, planning, or budgeting and forecasting. As these processes provide much of the data required for tax, it is becoming common to see EPM being used for tax. The advantages of using an EPM for tax are many – such as a reduction in the manual work for extract, transform, load (ETL); a reduction of reconciliation; and improved analytics functionality – but the strongest is creating a single source of truth.

At the very least, an EPM could be deployed as a staging database even where the current data is incomplete, with data captured through a supplementary pack that can be added to that database.

If ERP and EPM are set up properly, organisations could also leverage these systems for accounting for income tax; country-by-country reporting; environmental, social, and governance (ESG); and BEPS 2.0.

The concept of a tax data warehouse is not new. However, if we leverage the enterprise systems, it has the potential to improve the return on investment on the enterprise system and organisations may save on training and increase productivity.

Once the data is in a central place, the efficiency of processes should be obvious: starting with group generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), subject to adjustments to produce local GAAP, then applying permanent and timing differences to arrive at tax liability, from which you can perform a BEPS pillar two or QDMTT calculation.

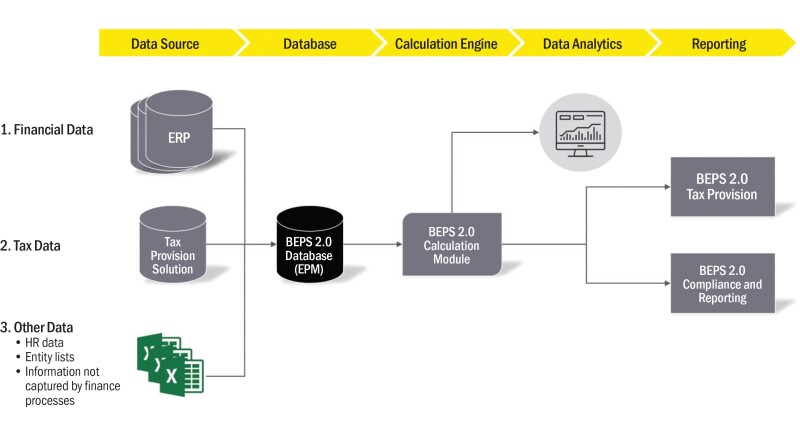

Diagram 1 shows an overview of how to leverage your enterprise reporting systems for BEPS 2.0.

Diagram 1

Time is limited. If you work backwards from the start of 2024, allowing for a quarter of parallel run, you have to allow at least six months for implementation, which would include design, configuration, testing, and rollout. In EY’s experience, it also takes time to obtain budget and approvals. An EY survey found that 81% of Fortune 500 companies expect to invest in tax technology over the coming three years and that 70% are expecting to acquire, upgrade, or update their ERP systems in the coming two years.

If there is an ERP or EPM transformation initiative under way, quickly seize the opportunity to incorporate the new requirements.

So, where to start?

A broad impact assessment is important. That is a review or assessment modelling of the impact of the new rules and whether any additional taxes are to be paid, then the impact on tax accounting and reporting.

Through performing the tax and financial analysis, the data and systems requirements and gaps should also be noted. By taking inventory of your current technology stack, you will be able to leverage your systems investments and processes, and accelerate your solution for BEPS 2.0.

From this broader work, a high-level design, a roadmap, and, most importantly, a budget or business case can be developed. This business case is critical to get on the C-suite or the board’s agenda as early as possible so that your organisation can be ready for BEPS 2.0.

The views reflected in this article are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the global EY organisation or its member firms.