This article is one of four in a series covering the transfer pricing implications emerging as the world transitions to a global low-carbon economy. An insight into the increasing role green finance is likely to play in corporate capital structuring and the impact this will have on intercompany funding policies is provided below.

The article presents some high-level points that tax and treasury functions should think about from a transfer pricing perspective if they are supporting multinational groups that have already issued, or are considering issuing, green financial instruments.

Consideration of the tax and treasury policy implications for intercompany funding arrangements supported by underlying green financial instruments is particularly relevant at present given the recent changes to the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, which were most recently updated in 2022. The changes include a new chapter focused on the transfer pricing aspects of financial transactions and serve to formalise the core principles relevant to intercompany financing more generally.

Increased momentum

Green financing connects with the broader concept of sustainable financing, whereby corporates are looking to utilise dedicated pools of capital to transition and transform their operations, products and services, and broader value chains. The objectives are:

To improve organisational resilience;

To enhance competitiveness and drive growth;

To fulfil environmental, social, and governance (ESG) commitments; and

To lower the overall cost of financing.

The increased momentum in this area in the corporate sector is a result of investors, consumers, and employees, as well as other stakeholders, making more active choices to ensure their investment and purchasing decisions and employment choices align with their values and commitments in a low-carbon, sustainable future. This change in investor, customer, and employee preferences is putting greater pressure on corporates and the banking sector to increase transparency with regard to where the proceeds of funds are directed, and is giving rise to new financing instruments/products.

Broadly, green financing is any financial instrument/initiative for which the proceeds will be applied entirely towards green projects or activities that promote climate change mitigation, adaptation, pollution prevention, energy efficiency, or other environmentally sustainable purposes. Green financing can take many forms, including the issuance of green bonds, green initial public offerings, and private equity.

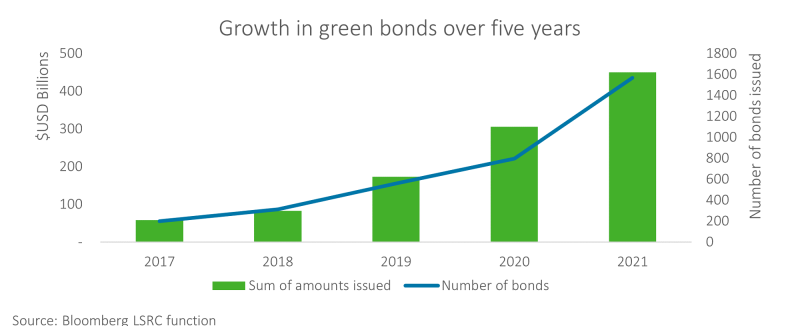

Over the past decade, the issuance of green bonds, a subset of green financing, has grown exponentially as the primary financial instrument utilised for green financing. According to Bloomberg data analysed by Deloitte, green bonds issued in 2021 stood at $450.1 billion, up from $58.6 billion in 2017. The chart below depicts the growth in green bond issuance over the five years before 2022.

The increased issuance of green/sustainable bonds means that, according to Bloomberg data Deloitte has analysed, there was over $1 of green bond funding issued for every $10 of funds issued in the market in 2021. The rapid growth in the issuance of green finance is set to continue. According to BloombergNEF, despite the increase in green bond issuance, green financing must triple in the next few years to be considered on track to meet net zero by 2050 and reach various country-specific pledges.

This rapid increase in the issuance of green bonds means it is only a matter of time before corporate tax and transfer pricing teams will be required to consider these green instruments and how they interact with their intercompany financing policies.

The greenium and other key features

One factor contributing to the growth in the global capital stock of green financial instruments is the ‘greenium’ (green premium) they attract. This is reflected in the premium at which green financial instruments often trade at above comparable non-green instruments with the same features.

In the case of bonds, given that bond prices are inversely related to their effective interest rates, the greenium provides a lower cost of capital for corporates that issue them. In addition, an increasingly large universe of bond and equity investors now have set mandates to increase their holdings percentage of green financing instruments in their portfolios. This presents an additional benefit to the corporate. According to ING, the greenium observed on euro-denominated bonds in 2021 was between 1 basis point (bp) and 3bps, whereas in US dollar-denominated bonds, this was as much as 5bps to 8bps. Local Australian loan and bond investors indicate pricing advantage to green-linked bonds and loans equate to savings of 10 to 15bps.

To qualify as a green bond, a corporate bond issuance typically adheres to qualifying criteria established by an independent authority. The OECD cites the Climate Bonds Initiative standard and the Green Bonds Principles framework, issued by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), as the most frequently applied standards adopted for corporate green bond issuances.

For a corporate to issue a bond and for it to qualify for green status, it must meet the following criteria:

Use of proceeds requirements – the issuer must clearly outline that the net bond proceeds will be entirely designated for market-accepted green activities;

Project selection requirements – the issuer of a green bond should outline the decision-making process it follows to determine the eligibility of projects;

Management of proceeds requirements – the net proceeds of the green bond should be tracked by the issuer and attested to by a formal internal process or if proceeds are credited to a dedicated account; and

Ongoing reporting requirements – issuers should report on the projects financed, project performance, and, preferably, the environmental impact at least once a year.

In summary, the key feature of green bonds is that, all things being equal, they offer a lower funding rate while requiring, for qualification purposes, an additional layer of restrictions and unique compliance reporting requirements.

Transfer pricing policy considerations

From a transfer pricing perspective, the key features of sustainable financing, including green bonds, present unique challenges to the intercompany funding frameworks of multinational groups.

Tax and treasury teams that operate central treasury entities in different locations should be aware of these challenges to ensure they have appropriate policies and systems in place to allow for green funding raised in one entity to be smoothly provided to fund-operating entities in other jurisdictions.

The key issues tax and treasury teams should consider include the following.

Green financial instruments are not fungible

Many multinationals centralise their treasury and finance operations so that it is one entity’s role in the group to raise capital as cheaply as possible to fund the group’s assets. Operationally, this means that treasury entities often pass funding acquired from third parties in the bond market or from banks and other sources to related entities that own the group’s operating assets.

To streamline the transfer pricing policies in place to support this funding model, many multinationals operate with a funding framework that effectively blends all third-party commercial funding sources raised at the central treasury level so that financing sources provided to operating assets are fungible. Consequently, intercompany funding passed down to related entities is often a mix of funding sources from third parties.

In the case of green bonds, where a specific set of defined and pre-approved assets must be connected with the funds raised, it is not possible to blend green funding with the broader funding portfolio of the group. Indeed, doing so may risk voiding the ICMA-awarded ‘green’ status of the initial funding or breach loan covenants (see the illustration below). This would result in the group missing out on the greenium benefit associated with the green status or it may even result in default events.

Consequently, it is important that multinational group funding frameworks are updated to allow for the accurate delineation of green funding sources so that these can be separated out in policies and tethered to the specific green assets funded.

Green finance may necessitate new intercompany agreements

Given that green bonds are likely required to be referrable to green assets, the standard template intercompany agreements often used by groups to execute intercompany funding arrangements may not be appropriate. For example, the agreements may need to be tailored to better mirror the actual green financial instrument issued to the market. This may include:

Adding clauses to track unique green requirements associated with the ICMA designation;

Specific emissions reductions targets; and/or

The formal legal designation of specific green assets that the funding is secured against.

Updates to intercompany agreements would likely be expected to be similar in principle to those outlined in Section C.1.1.5 of Chapter X of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines with respect to the treatment of covenants in financial transactions.

How is any greenium achieved going to be shared?

Consideration should be given as to how any greenium achieved from green funding sources should be shared across group entities. For example, if one entity raised the green funding and put in all the necessary effort to issue the instrument, maintain it, and, in turn, on-lend those funds to the owner of the underlying green assets, then consideration should be given to which group entity (i.e., the raiser of the green funding, the green asset holder, or both) should benefit from any greenium achieved.

It is likely that the principles in Section D.8 of Chapter I of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines around group synergies and centralised procurement functions, as well as broader commentary on rewards to treasury activities in Section C of Chapter X of the guidelines, should be considered with respect to any greenium the group achieves. The application of these guidance principles should be addressed in contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation.

The comparability of green financial instruments

For most traditional non-green financial related-party debt instruments issued, various comparability factors impact the interest rates charged between related parties. As a result, publicly available benchmark interest rates are often used to make adjustments for differences in the term of the funding provided and the currency the funds are denominated in, among other features.

With regard to pricing green financial instruments, it may be more challenging to adjust for green features in the arrangements in question accurately and this may make benchmarking these instruments more challenging.

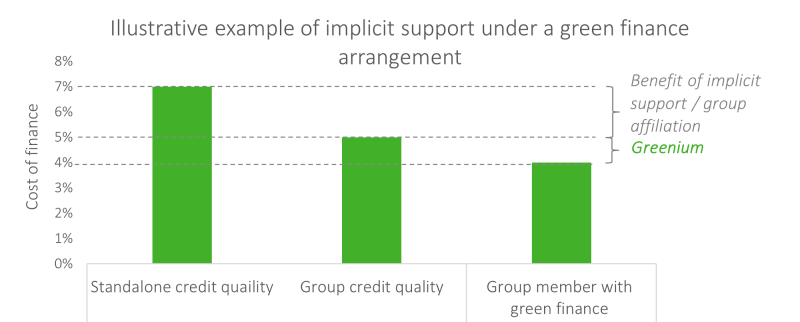

How is implicit support considered

Similar to the scenario above, if one group entity raises the green funding at a discount, but the lender has also taken into account implicit support provided by the borrower’s membership of a multinational group, in the absence of a formal intercompany guarantee agreement, consideration should be given as to how much of the discount relates to the green assets underpinning the financing arrangement, as opposed to the implicit support. See the illustration below for an example of the impact this may have on the arm’s-length cost of finance.

It is likely that the principles around the effect of group ownership, implicit support, and guarantees set forth in sections C.1.1.3 and C.1.1.6 of Chapter X of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines should be considered with respect to any potential support provided in the green finance arrangement.

How are intangible assets funded

Consideration should be given as to whether components of the green assets to be financed would be funded wholly by debt or with a mix of debt and equity. This may be particularly relevant if:

The green project being funded involves capital-intensive technologies that remain in an uncertain phase of commercial development (for example, operations that involve carbon capture or seaborne hydrogen export); or

The proceeds from the green financial instrument are intended to fund a green project in its entirety at the group level, but the funding is allocated across multiple entities in different jurisdictions at the intercompany level. For example, funding is split and shared with one entity that owns and develops the property, plant, and equipment assets and another entity that owns and develops the relevant intangibles, such as know-how and patented technologies.

In these scenarios, consistent with the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines on the analysis of risks in commercial and financial relations according to Section D.1.2.1 of Chapter I and narrower specific guidance on intangible assets in Section D.3 in Chapter VI, a specific analysis may be required for each entity factoring in its relative contributions to the overall project, including the risks it has assumed. The outcomes of this analysis may inform the appropriate arm’s-length funding structure and associated interest rates to be applied to each entity.

The critical activities each entity performs, assets it owns or develops, and risks it bears should be carefully considered and well documented in contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation.

The need to calibrate ERP

ERP platforms play a critical role in managing the necessary data required for tax and transfer pricing reporting. In the case of green finance that is required to be closely associated with specific green assets, ERP systems may need to be calibrated so that they:

Can appropriately ring-fence any green assets so as to ensure any green bond requirements are adhered to and the green funding is not tainted by other assets or development costs related to those assets; and

Are equipped to provide the necessary operational data to track and align any environmental targets specific to the green financial instrument. For example, the need to track emissions produced by an asset.

Looking to the future

The change in investor sentiment towards favouring ESG initiatives, combined with the greenium available to the issuers of green finance, is likely to mean green financial instruments continue to grow and become an increasingly common feature of global capital markets. It is only a matter of time before this growth is mirrored in related-party transactions as green finance raised in commercial markets is pushed down to operating entities holding green assets.

This article has identified the key points tax and treasury teams will need to consider to best manage the transfer pricing implications that the introduction of these instruments will bring to their business. This will likely require work to update intra-group funding policies, intercompany agreements, and transfer pricing documentation to better capture the differing functional profiles of funding and asset-holding entities and to calibrate ERP systems to manage those operational changes.

Tax managers and treasury teams would do well to get on the front foot on these issues and apply appropriate resources in parallel with initiatives to issue green finance instruments, in order to prevent a reactionary approach to managing any transfer pricing and tax exposures that may develop.

Deloitte accepts no duty of care or liability to you or any third party for any loss suffered in connection with the use of this article.

© 2022. For information, contact Deloitte Global.