One of the primary objectives of any M&A transaction is to create value for the shareholders through synergies and cost savings. While the necessary success of an M&A transaction is reliant on a wide range of factors across many phases of the project, it is often only in the integration phase that a company can begin to see whether new organisation can achieve the predefined objectives and realise the intended synergies.

Numerous surveys have shown that underestimating the importance of a well-defined and timely post-merger integration (PMI) plan is a common feature in failed M&A transactions. This article will discuss the significance of tax in PMIs and how tax departments can help to maximise value in the Asia-Pacific region.

The importance of early planning

As tax considerations can play a critical role in PMIs and can have a significant impact on the overall value of the deal, preparation for integrating two previously independent companies should begin well before closing. Companies must take into consideration the tax implications of the transaction, both pre- and post-closing, to ensure that they can maximise the value of the deal and minimise the tax consequences.

The following are some of the key tax considerations that companies should consider while planning for a PMI:

Transfer pricing – transfer pricing is the process of determining the price at which goods and services are traded between different units of the same company. As merged companies often have different approaches to intercompany pricing, companies must ensure that consistent transfer pricing policies are in place to avoid any potential tax implications that may arise from intercompany transactions.

Tax structure – the tax structure of the two companies involved in a merger or an acquisition should be evaluated to determine the most efficient structure for the combined entity. This may involve the transfer of assets and liabilities between the companies to optimise the tax position, a combination or rationalisation of duplicative entities, group relief potential, etc.

Tax incentives – companies must also consider the tax incentives that are available in each jurisdiction – such as tax holidays, tax credits, and tax exemptions – to minimise the tax consequences of the transaction.

Systems – often the ERP and tax-related systems used by the target company are not aligned with the systems used by the buyer. Conversion or modification of the target systems may be necessary to ensure consistent data and tax reporting.

People resources – depending on the situation, often the target company has its own tax group that will need to be integrated with the buyer company tax group. Considerations on where the combined tax function will reside and how they will work with the existing tax function are critical to ensure continuity of tax matters.

Cross-functional items – the tax department will often need to be deeply involved in workstreams owned by another group, such as tax and purchase accounting; legal entity matters such as IP management or entity rationalisations; treasury functions such as cash management or debt pushdown; and HR changes to compensation or retirement plans.

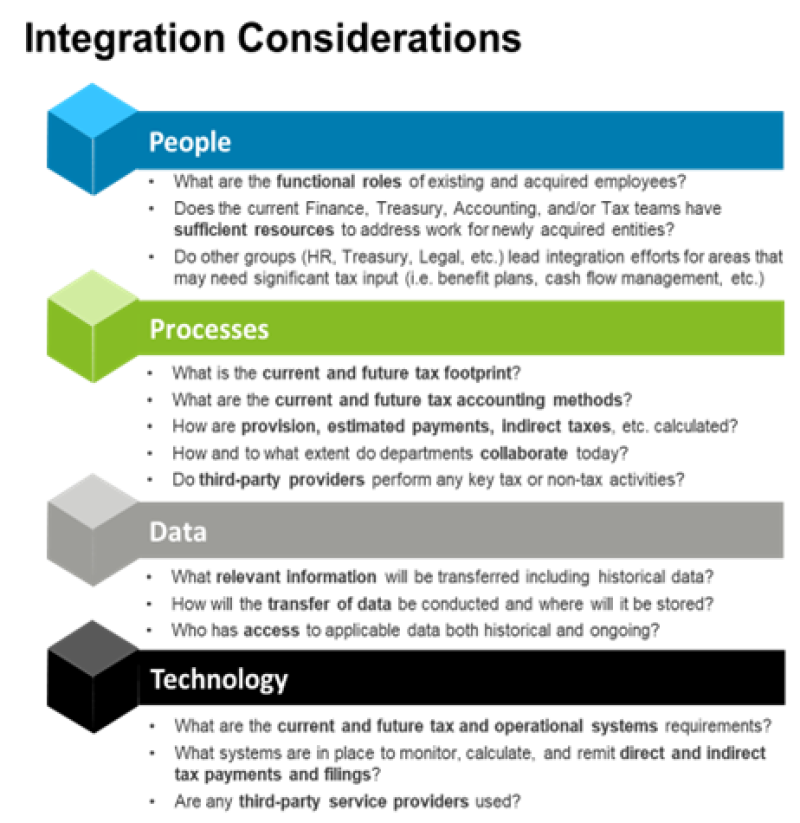

Other integration considerations, both tax and non-tax, may need to be considered, as follows:

Whatever the integration strategy, it is important to have a well-developed written PMI plan including cross-functional dependencies, a RAID (risks, assumptions, issues, and dependencies) log of important items, and other PMI management tools.

In virtually all M&A transactions, one of the most obvious aspects of PMI planning is addressing (and, if possible, remedying) historical tax issues that have been identified in performing due diligence. With the goal of due diligence generally being to understand the target’s tax profile and the tax issues/opportunities that a purchaser will inherit, there are often historical tax exposures that need to be carefully managed.

This ‘clean-up’ can take various forms, including:

Requests for tax assessments to be amended;

Voluntary disclosures of historical errors;

New business arrangements in capturing the under-reporting transactions;

The curing of uncertain filing positions to avoid potential exposure to penalties.

Additionally, most M&A transactions will require a careful re-examination of the existing cross-border intercompany agreements and the establishment of post-deal commercial arrangements for item such as transfer pricing, customs declarations, withholding tax on loan and royalties, tax treaty relief, beneficial ownership qualifications, interest limitation rules, exchange control regulations, and the deductibility of transaction-related expenses.

Some country-specific PMI issues that may need to be considered in a well-planned PMI plan are outlined below.

China

Day 1 readiness checklist

In China, challenges often occur in post-deal operations under China's complex regulatory environment. The purchaser may need to navigate the myriad of tax, accounting, legal, regulatory, cultural, and labour issues as part of their PMI. A carefully designed Day 1 readiness checklist would help the purchaser to have an efficient integration process from the beginning and therefore obtain the required value from a deal, with minimal disruption to their existing businesses.

The checklist may include common integration tasks, such as those below, and should be designed to cover more specific considerations for post-deal integration.

Legal form selection for the new entity(ies) to be established;

Application/extension of government subsidies and incentives made available to certain industries;

The establishment of initial local accounting policies and selection of a local accounting software system;

A tax compliance calendar and tax audit risk-control measures; and

Registrations on foreign exchange control, financial disclosure and other statutory requirements.

Intra-group restructuring

Closing a deal is often followed by an intra-group restructuring in response to the business needs of the market. Where a Chinese company is acquired indirectly, there are still Chinese taxes levied on a gain in the Chinese entity’s shares. In such circumstances, it is often desirable to obtain a tax basis step-up of the Chinese company’s shares to reduce any tax cost of subsequent restructurings.

There are numerous challenges in obtaining this step-up of tax basis arising from the uncertain timeline to complete the reporting and tax settlement for the indirect share transfer of the Chinese company. If the intra-group restructuring takes place before the tax base step-up is secured, the purchaser may need to agree with the relevant tax authority on a case-by-case solution to avoid overpaying tax.

India

Legal entity consolidation

India does not have a group consolidation regime and, as such, each entity forming part of a consolidated group in India must report its income independent of other constituents of the group.

As a result of an acquisition, the acquirer may have multiple entities in India with similar businesses filing separate tax returns, resulting in tax leakage from varying levels of profitability and interest limitation rules.

It is therefore common for businesses to consider a legal entity consolidation after an acquisition. A legal entity consolidation would require careful evaluation to understand the consequences, such as:

The ability to carry forward tax losses of the entities being absorbed;

Overall alignment of the tax policies of both entities; and

The transfer of tax credits.

In addition, a legal merger would require the approval of the regulatory authorities and would be subject to stamp duty.

Tax incentives

An acquirer may have expansion plans to be implemented after acquisition. India has a special tax regime that confers a lower tax rate for new manufacturing companies which commence manufacturing before March 31 2024. To be eligible, the acquirer would have to register a new company in India which would establish a new manufacturing unit. The acquirer will have to carefully evaluate if it fulfils the other conditions for availing itself of the lower tax rate.

Japan

Group tax regime

Under the new group tax relief regime, tax losses of a parent company may be lost or become subject to limitation under the ‘separate return limitation year’ (SRLY) rules.

The SRLY rules limit the offsetting of parent company losses to future profits of the parent and not the other group members. On the other hand, Japan’s corporate reorganisation rules continue to offer the ability to offset losses via a merger. For example, if a profit-making subsidiary is merged with a loss-making entity in the corporate group and certain requirements are met (such as ownership relation and a joint business requirement), then existing losses of the surviving entity can still be used to offset the post-merger income. This provides a significant tax-saving opportunity after a merger.

CFC exposure on target-side entities

As part of its anti-tax avoidance measures, Japan has a controlled foreign corporation (CFC) regime. This regime discourages Japanese corporations from operating through foreign subsidiaries set up in low-tax jurisdictions and lacking commercial substance, by taxing the profits of the foreign related company in the hands of the Japanese parent corporation.

When contemplating an acquisition, particular attention should be given to the foreign subsidiaries of the target group and whether the Japanese ownership ratio in such subsidiaries could exceed 50% upon closing of the transaction. If yes, then a detailed analysis should be carried out on the effective tax rates, economic substance, passive income, etc. of each foreign related company to assess the Japanese CFC impact on the Japanese shareholders. Based upon the assessment, the PMI stage could involve legal entity rationalisation or tax planning at the level of the relevant foreign subsidiaries.

South Korea

Post-merger restructuring

Korea imposes a transfer tax for each movement of the ownership of a Korean entity’s shares. Furthermore, unless the value of the Korean entity is agreed in the original acquisition agreement between the independent parties, the Korean tax rules may require that the subsequent transfer of Korean shares be conducted at a value calculated by a formula provided in the Korean tax laws. As such, any future restructuring plans should be contemplated as early in the process as possible and potentially a value assigned to the Korean entity in the stock purchase agreement to avoid unexpected valuations and additional stock transfer taxes.

Furthermore, Korea allows for tax-free/deferred mergers in certain situations. Specifically, a merger between a parent and a wholly owned subsidiary in Korea can be deemed to be a qualified tax-free merger and avoid post-merger limitations that would be applicable to other mergers. Ensuring that the newly acquired Korean subsidiary is properly placed in the legal structure at the time of acquisition to take advantage of such rules would be beneficial.

New Zealand

Tax elections

A number of New Zealand tax elections and registrations need to be considered after completion. These may include:

Forming an income tax consolidated group, which can help to maximise the deductibility of expenditure, particularly where the target has been acquired by a newly incorporated New Zealand holding company;

Forming a goods and services tax (GST) group, so that intercompany transactions are disregarded for GST purposes; and

Electing into the ‘business-to-business’ regime, to maximise GST recoverability on ‘financial services’ (which are very broadly defined for GST purposes).

Location of IP

Unlike many other Western countries, New Zealand does not have a comprehensive capital gains tax, nor does it impose an IP ‘exit charge’ or stamp duty/transfer tax. Where multinational groups hold IP in particular countries, it may be commercially appropriate for the New Zealand target’s IP to be ‘migrated’ offshore. This can often be achieved in a number of ways (for example, by way of a distribution subject to tax treaty relief) and will generally need to be considered before the acquisition structure is implemented.

Southeast Asia

Challenges of post-merger integration

Typically, a PMI exercise considers legal entity rationalisation/restructuring and alignment of business models or transfer pricing methodologies, etc. Each consideration comes with its own unique challenges and hurdles depending on the tax regimes of the jurisdictions concerned. For example, where legal rationalisation is contemplated, the acquirer may need to grapple with capital gains tax and indirect share transfer rules in Vietnam, real property gains tax in Malaysia, or a capital versus revenue argument on disposal gains in Singapore.

However, on the upside, there are tax deferral schemes available for business transfers and mergers, as in Thailand and Indonesia, and stamp duty relief mechanisms in Singapore and Malaysia if the conditions can be met.

Tax incentives

Many Southeast Asian countries have tax incentives to promote investments. The acquired entities may benefit from such tax incentives. Certain jurisdictions within Southeast Asia may require a specific approval or notification to be made to the relevant authorities when these incentivised entities are acquired; for example, the Board of Investment in Thailand, or the Singapore Economic Development Board.

Final thoughts

The value of tax in PMIs cannot be overstated. Tax planning and optimisation play a critical role in ensuring that the combined entity is able to fully realise the synergies and benefits of the transaction. Moreover, as the combined business adjusts its business and operating model to reflect the value of the combined entity, so must the tax strategies (value chain, tax risk, tax profile, etc.).

Companies that prioritise tax planning and optimisation in the PMI phase will be well positioned for long-term success.