The case

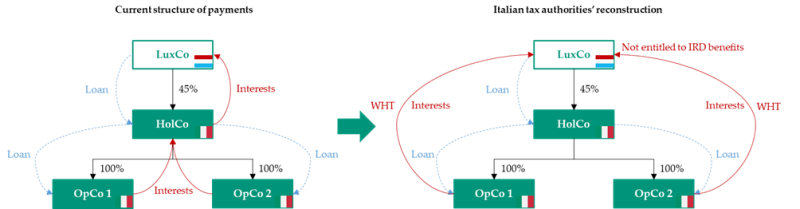

Two Italian subsidiaries (OpCos) received a credit facility from their direct controlling holding company (HoldCo), which is also an Italian tax resident. HoldCo was financed by a Luxembourg company (LuxCo) which also owned 45% of HoldCo share capital. It is not known how LuxCo was funded. The Italian tax authorities claimed that:

The interest payments made by the OpCos should be considered as made directly to LuxCo;

LuxCo was the beneficial owner of the payments made by the OpCos but was not entitled to benefit from the exemption provided by the Interest and Royalty Directive 2003/49/EC (IRD), due to the absence of a direct participation in the OpCos; and

(iii) OpCos should have applied the withholding tax provided for interest payments to non-resident companies under Article 26(5) of Presidential Decree No. 600 of 1973.

The Decisions

The Supreme Court judgments No. 6050 and 6079 of February 28 2023 (the “Decisions”) acknowledge that even a sub-holding company with a "light" but adequate structure can be considered the 'beneficial owner' of payments. As per the Decisions: "at the end of the assessment of some 'detector parameters', which indicate the control and independence of the management of the income flow, as well as the absence of indices of artificiality and abusiveness, as outlined by the case law of the Court of Justice".

In this respect, three separate tests must be passed:

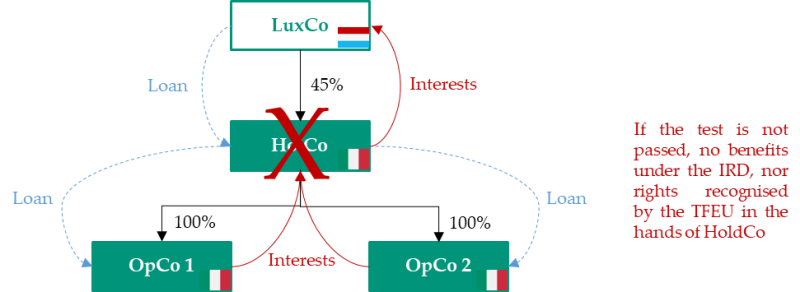

The substantive business activity test, to assess whether the company receiving the payments is an artificial arrangement. If this is the case, that company won’t be eligible for benefits under the IRD, nor will it be able to avail itself of the bundle of freedoms and rights recognised by the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

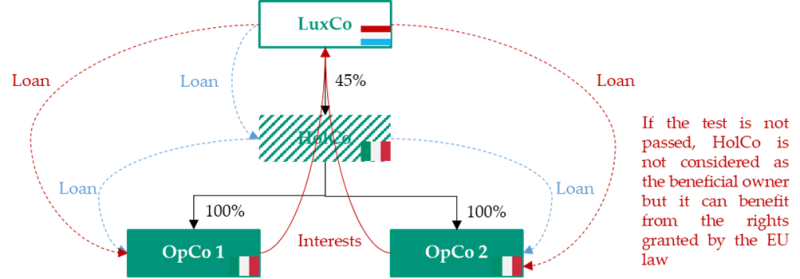

The dominion test, that "focuses on the heart of the economic significance of the transaction (substantial economic effect)”. The test is passed if the recipient can freely dispose of the income received and is not obliged to pass on the income stream to a third party, either by contract or based on factual analysis.

Facts that may be relevant for this test are: “the short period of time between the cash in of the interest and the payment of the instalment of the loan; the regularity of the transfers to the parent company; the small margin of profit on the interest received; the identity of the management of the interposed company and that of the final recipient of the income flow; the circumstance that the interposed company did not approve the loan, that it does not bear the risk, or that it cannot waive the sums lent”. If the dominion test is not passed, the company cannot be considered as the beneficial owner, but it is not precluded from enjoying the other rights and freedoms enshrined in European law.

Finally, the business purpose test, which investigates why the income stream is being diverted. It aims to determine whether the 'triangulation' is designed only for the purpose of tax saving or whether it is economically motivated.

The Supreme Court, adopting the position of the CJEU, then specified that if "the third company for which the conduit company acts fulfils the requirements to benefit from the exemption regime of the Convention or the Directive, the tax benefit must be recognised (so-called look-through approach)".

Analysis

The Decisions stimulate two distinct comments about:

The notion of beneficial owner; and

The impact of the look-through approach as applied by the Supreme Court.

As far as the notion of beneficial ownership is concerned, the Supreme Court leaves no room for uncertainty and establishes that a company must meet certain standards for invoking the application of the IRD. Such company:

Must be operative, even with a light structure, provided it is proportionate to its activity. However, the Decisions do not clearly define what characteristics a finance company should have to successfully pass the test. Although the need for a case-by-case analysis is recognised, there are still concerns that certain elements, such as having highly qualified employees, are essential to avoid uncertainties. For instance, a finance company that solely issues bonds to third-party institutional entities and lends the bonds proceeds to its Italian subsidiaries with an arm’s length margin may not require such elements;

Must not act as an intermediary, a circumstance that cannot be based on the legal framework but must be proven by factual analysis. Unfortunately, despite the Supreme Court's identification of certain indicators, there are still uncertainties when it comes to applying these concepts in practice. For example, what is a reasonable period between the cash in of interest and the payment to the lending entity? What level of "margin on interest received" is acceptable? Does it refer to a margin that is below arm’s length standards? In any event, the reference to the "identity of the management of the interposed company and that of the final recipient of the income flow" seems inappropriate. It is a common practice within groups to appoint the same persons to cover unitary company functions (such as treasury management) even if they are located in multiple states; and

Must explain why the amount received has been paid to another entity, which seems, on the one hand, to overlap with the other two tests. and on the other, to authorise endless scrutiny of entrepreneurial choices.

The Supreme Court confirmed the applicability of the look-through approach, a criterion already endorsed by the Italian tax authorities, and its acknowledgment by the Supreme Court should be a positive development. However, the Decisions interpreted such criterion in a way that raises concerns.

Despite LuxCo being the beneficial owner, the Decisions denied it the entitlement to the IRD exemption from withholding tax. This is because, from a strictly formal point of view, LuxCo did not meet the IRD requirement of direct participation in the payers (OpCos).

Essentially, the Supreme Court applies to the income streams the tax regime that would have applied to the beneficial owner if it had received it directly from the first payer. But the Supreme Court does not go so far as to configure a 'fictio' of a direct holding in the first payer. This is an illogical application of the look-through approach, entirely undermining its rationale.

The rationale of the look-through approach is to investigate if the beneficial owner would have been theoretically entitled to benefit from a given regime, or if it attempted to obtain it by exploiting a third interposed party. If the interposer (i.e. LuxCo) is entitled to the IRD, the “interposition” of HolCo cannot be regarded as tax driven. Therefore, it should not be disregarded.

In fact, the cases where the IRD is typically challenged relate to non-EU parties interposing companies in EU states with a favourable network of conventions for taking advantage of the double exemption. In practice this is: the IRD exemption from the first EU country (e.g. Italy) to the second one (e.g. Luxembourg), and the favourable tax regime granted by treaty with the third country (e.g. the US). It is evident that this is not the situation outlined in the case at stake, being the beneficial owner an EU company.

However, given that the absence of a tax advantage excludes that the structure constitutes a wholly artificial arrangement, challenging the incorporation of a holding for business reasons in the same EU member state in which the operating companies are located seems, by itself, a breach of the fundamental freedoms.