This article serves as a companion piece to a webinar hosted by KPMG China on May 4 2023 which covered the rollout of BEPS 2.0 across Asia Pacific. Click here to watch a recording.

The last few months, since December last year, have seen rapid progress in several Asia-Pacific jurisdictions with their Pillar 2 implementation. While China tax policymakers have not yet given any firm indication of their Pillar 2 plans, China’s close economic links to its Asia-Pacific neighbours means its path forward in this space is intertwined with regional developments. In addition, China faces many of the same challenges as its neighbours on how the tax incentive mix should be changed, going forward, to maintain its attractiveness. This article gives an overview of these developments and looks at how businesses operating in Asia-Pacific, including China, need to get ready for the changes coming with Pillar 2.

Asia-Pacific Pillar 2 rollout

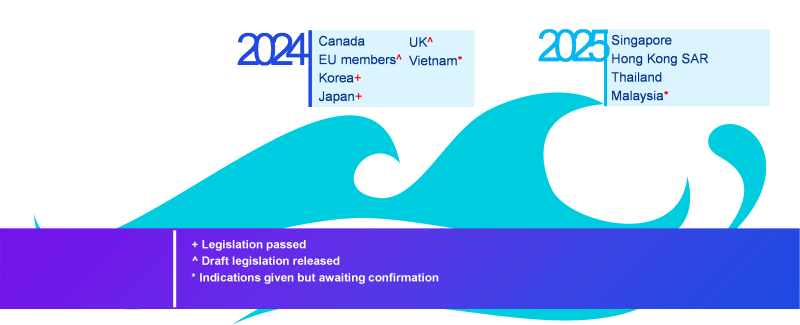

Jurisdictions committing to implement the GloBE rules are progressively sorting themselves into two ‘waves’. There is a first wave of jurisdictions moving to apply the Income Inclusion Rule (IIR) from the 2024 fiscal year, and a second wave of jurisdictions moving to apply it from 2025. In Asia-Pacific, at the time of writing, the first wave includes Japan, South Korea and (indicatively) Vietnam. These join countries in other regions, including Canada, the UK and many of the EU member states, also moving for a 2024 start. Several Asia-Pacific jurisdictions have also confirmed themselves to be in the 2025 wave, including Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, Thailand and (indicatively) Malaysia.

These Asia-Pacific jurisdictions then vary on whether they are set to bring in the qualified domestic minimum top up tax (QDMTT) alongside IIR or later. The undertaxed payments rule (UTPR), is generally set to be in effect in participating Asia-Pacific jurisdictions from 2025 onwards. However, Korea has yet to confirm whether it will move on this from 2024 or 2025 – this is discussed further below.

Having outlined the broad strokes of Asia-Pacific developments, more specific comments are now set out for specific jurisdictions.

Japan

The 2023 tax reform bill was passed by the Japanese Diet on March 28 2023 and provides that the IIR will apply to fiscal years beginning on or after 1 April 2024. It is expected that QDMTT and UTPR legislation will be contained in the 2024 tax reform bill, for an April 1 2025 effective date start.

A key focus in Japan has been on the financial reporting implications. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) has been busily working on updates to International Accounting Standard (IAS) 12 (Income Taxes) to exempt GloBE in-scope MNEs from the requirement to account for deferred tax in respect of GloBE tax. This reflects the significant challenges that arise in computing deferred tax in such cases. Japan GAAP is broadly aligned to IFRS and the Japanese accounting regulator would be expected to integrate the IAS 12 changes into local GAAP.

However, a timing issue emerges, heightened by the fact that most Japanese MNEs have March 31 financial reporting year ends, and some have June year ends. Take the case where “substantive enactment” of the Japan IIR rules, for accounting purposes, occurs before the financial year end of a Japanese MNE. If the IAS 12 deferred tax exemption was not yet in effect at that time, then the Japanese MNE would have to account for deferred tax in respect of GloBE tax.

It appears that, despite the passage of the Japanese IIR legislation at the end of March, “substantive enactment” would likely not be considered to occur until further detailed Japan IIR rules are released. These are to be issued in the form of cabinet orders and ministry guidance, likely this June. As the IASB is looking to finalise the IAS 12 updates in late May, this would frame the analysis for June year-end Japan MNEs. While Japan IIR substantive enactment may have occurred before their June financial year end, the deferred tax exemption would already be in effect at that time.

It must be emphasised though that there are a lot of moving variables here, including the final IFRS and Japan GAAP analysis. However, the analytical effort already invested in this “substantive enactment” matter in Japan is indicative of the exercise that will need to be individually undertaken for each Asia-Pacific jurisdiction and, indeed, each jurisdiction globally.

Korea

Korea raced out of the gates in December 2022, passing GloBE legislation at that time. This covers both the IIR and the UTPR and targets a 2024 fiscal year start. However, the Korean legislation was very high level in nature, being no more than three pages in length. The detailed rules are set to follow in a presidential enactment decree. Latest indications are that this may be issued in the late summer; this would also likely trigger substantive enactment from an accounting perspective at that time.

If Korea were to apply the UTPR from 2024 then this would put it ahead of other jurisdictions, who are generally targeting 2025. By pushing the enactment decree to late summer (it was originally anticipated for release back in February), the Korean authorities have given themselves latitude to see if other countries move ahead with a 2024 start for UTPR, before making a final decision. Given the implications for the many MNEs with Korean subsidiaries, developments in this space will continue to be closely monitored.

Hong Kong SAR, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia

In several public announcements over February and March, these jurisdictions firmed up on their Pillar 2 rollout plans. In its February budget announcement, Singapore, which had earlier been expected to start applying the rules from 2024, indicated that it would instead commence application of the IIR, UTPR and QDMTT from 2025. Hong Kong SAR, which contends with Singapore as a key hub in the region, subsequently announced that it would also apply the rules from 2025. Thailand followed and, indicatively, Malaysia.

Australia, Indonesia, Vietnam

There are countries in the region whose officials have given indications, at various points, that they plan to implement the GloBE rules, but which have not set out formal plans. Australian officials previously suggested that Australia could move to apply the IIR from 2024 – it is anticipated that further clarity might be forthcoming in May. Indonesian officials had initially indicated an intent to apply the IIR and QDMTT from 2023, then subsequently suggested 2024 at public events – however, no formal plan has yet been set.

Vietnam constitutes an interesting case. In March 2023 it was reported that, based on indications from local officials, the Vietnamese authorities planned to start application of the IIR and QDMTT from 2024, with the UTPR to follow in 2025. While no formal confirmation has yet been given by the authorities, the development is notable as it would make Vietnam the sole developing economy (so far) to move on GloBE implementation in the 2024 wave.

China and India

Neither China nor India tax policymakers have yet set out any firm plans on Pillar 2 implementation. Though the general expectation is that both will adopt at least the QDMTT in due course, to preserve taxing rights over local tax resident entities. The China considerations are delved into in greater detail in the following section on tax incentives.

Future of tax incentives in Asia Pacific

A top-of-mind question for many governments in Asia-Pacific is how they can maintain their investment attractiveness in a post-GloBE world. Earlier KPMG research in this space, published in 2021, observed the degree to which tax incentives are a major feature of the Asia-Pacific tax landscape. It further observed how the types of tax incentives traditionally favoured in the region, such as tax holidays, low rates, and exempt income classes, are at particular risk of clawback under GloBE. This is equally the case for China and would play into China tax policy thinking on GloBE.

Looking at some of the key features of the Asia-Pacific incentives landscape:

At least 14 jurisdictions across the region offer tax holidays for certain industries, many of these directed at the manufacturing, power generation, infrastructure and technology industries. At least nine jurisdictions offer similar benefits to entities set up in special economic zones. Typically, the tax rate will be set at nil for a fixed period (ranging from three to 20 years), followed by a reduced rate for several years. In China, such incentives are provided for enterprises in the infrastructure, semiconductors, and software space, as well as others. Such incentives are particularly exposed to GloBE clawback given that they provide permanent benefits – these are not protected by GloBE rule deferred tax adjustments in the same way as temporary benefits.

At least seven jurisdictions in the region offer activity-based or industry-based low tax rate incentives. This includes regional headquarters, treasury centres, intellectual property, global trading, financial services, shipping and aircraft leasing. In most cases, the incentive rates sit between 5-10%. Hong Kong SAR, for example, has notable aircraft leasing, shipping, insurance and treasury centre incentives of this sort. As with tax holidays, these permanent benefits are exposed to GloBE clawback. However, given that they may be limited to certain income streams of an entity, this does provide more room for jurisdictional blending.

Many of the jurisdictions in the region offer R&D incentives or enhanced deductions for certain industries. This can be in the form of non-refundable tax credits, refundable tax credits, enhanced or accelerated deductions or grants. These then run the gamut from GloBE-protected to GloBE-exposed. China’s incentives in this space also run the spectrum, with generous accelerated depreciation provisions being protected through GloBE rule deferred tax adjustments while China’s R&D bonus deduction is exposed.

Several Asia-Pacific jurisdictions provide an exemption from tax for certain types of income, such as income from government bonds, debt securities and venture capital investments. Others provide exclusions for foreign sourced income via (semi) territorial tax regimes. These are exhibited in both mainland China (e.g., government bond exemption) and Hong Kong SAR (e.g., the recently updated foreign-sourced income regime).

With the Asia-Pacific Pillar 2 rollout schedule and tax incentives landscape as context, the following considerations face China tax policymakers.

Many major Chinese MNEs have corporate structures designed to facilitate overseas listing. This means that, in many instances, entities that are tax resident in Hong Kong SAR sit above the mainland China operating entities. In the absence of a mainland China QDMTT, a Hong Kong SAR IIR would ‘pick up’ top up tax calculated in respect of the China operations. However, the recent deferral of the Hong Kong SAR IIR to 2025 means that this will first become an issue from 2025.

For MNEs with mainland China ultimate parent entities, a key focus will be on whether the incentives provided at China level could be clawed back via other countries UTPRs in 2024. While there remains a possibility that Korea could apply its UTPR from 2024, on balance it appears more likely that it will seek to align with other countries on a 2025 start. As such, China level incentives would likely first be exposed from 2025 for such cases.

With these factors in mind, and given the lack of any indications from the policymakers of a move to start GloBE application from 2024, the current mainstream thinking in China is that the rules will be brought in from 2025. Whether this would just include the QDMTT and IIR or also extend to the UTPR remains to be seen.

With regards to incentives, it has been observed above that several of the China tax incentives are exposed under GloBE. Given that many groups operating in China have significant local substance, in terms of staffing and tangible assets, the higher transitional mark-up rates under the substance-based income exclusion (SBIE) could serve to protect the value of some tax incentives. Another consideration is that groups operating in China can have many entities, some benefitting from tax incentives and others paying the full 25% CIT rate. In this context, jurisdictional blending may apply, though it is noted that the GloBE Administrative Guidance (AG; released in February 2023) gave countries the latitude, when designing their QDMTTs, to apply a stricter approach to blending.

When China tax policymakers come to consider what could be done to maintain incentive attractiveness post-GloBE, they will likely pay close attention to emerging trends elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region. For certain industrial sectors and activities, such as many areas of manufacturing, it will primarily be other countries in the region competing for this investment. While no country in the region has yet launched wholesale changes to their palette of incentives, there are emerging indications on the direction of travel. Countries offering tax holidays seem likely to move these in the direction of moderate incentive rates. Somewhere in the band from 10-15% is considered sustainable, once blending and SBIE have been considered. There may well be greater reliance on grant programs.

In this regard it is notable that Thailand is looking at directing revenues, raised through their QDMTT, to a national Competitiveness Enhancement Fund for Targeted Industries. This could be used to provide new incentives, including grants, to support industrial development. One could also see countries in the region looking to improve their expat tax regimes, to lower costs for inbound investing MNEs, or enhancing their VAT refunds for exports, etc.

Developments are moving quickly in the region, meaning that policymakers and businesses need to keep a close eye to developments. Turning now to businesses, a few points merit emphasis.

Businesses getting ready for Pillar 2

With all this in mind, there are certain points of focus for businesses operating in Asia-Pacific, including in China.

Safe harbours:

Given the number of jurisdictions making moves to have the GloBE rules in effect from 2024, most large MNEs (with revenue exceeding €750m) are likely to have at least some entities in jurisdictions applying the rules from 2024. For example, large Chinese MNEs can be present in upwards of 100 jurisdictions. Given the amount of effort required to conduct the detailed effective tax rate (ETR) calculations, MNEs are necessarily keen to maximise use of the transitional safe harbours (TSHs), particularly the simplified ETR test. This leverages both financial statement data and CBCR numbers.

However, the quality requirements set for their use have led some MNEs to be concerned that they will not be permitted to use the TSH. For example, there may be groups that use (acceptable) audited financial statement information for their CBCR numbers for most jurisdictions, but then use (potentially unacceptable) management accounting numbers for the CBCR figures for a smaller number of countries. Ensuring that CBCR data meets the TSH requirements has thus become a focus for MNE preparatory work. They will also be monitoring closely to ensure that the TSHs built into QDMTTs are aligned to the GloBE model rule TSH design.

Financial reporting:

As illustrated above in the comments on Japan, MNEs are closely monitoring to identify jurisdictions where the GloBE legislative process is on the cusp of crossing the “substantive enactment” threshold for accounting purposes. The financial reporting implications of GloBE tax will strike some time before any GloBE tax payments or filings need to be made. IAS 12 provides for specific disclosures on an MNE’s exposures to GloBE tax, across jurisdictions, when “substantive enactment” has occurred before year end (even though the rules may only enter effect in a subsequent year).

However, investors may expect disclosures on the potential impacts even if there has been no “substantive enactment” prior to financial year end. MNEs are wrestling with the implications for financial reporting where their jurisdictions of operation are moving at varying speeds on enactment and effective dates. This includes instances where the enactment picture across relevant jurisdictions looks different for the interim financial statements than for the year-end financial statements. China GAAP also looks set to see the relevant IAS 12 updates, meaning that Chinese MNEs will also need to contend with this. In parallel, it is notable that Australia is pushing ahead with public CBCR requirements which reference Pillar 2 ETR calculations; China groups with Australian subsidiaries would need to take this into account in parallel.

Data inputs:

Linked to the financial reporting challenge is the significant undertaking faced by MNEs in obtaining the requisite accounting data to conduct GloBE ETR calculations. In particular:

Data granularity:

The starting point for the GloBE ETR calculations is the local accounts of the MNE group entities in a jurisdiction, as conformed to the group GAAP and stated in the group functional currency. In practice, many groups can face difficulties in preparing such entity accounts at the required level of ‘granularity’ needed for GloBE ETR calculation purposes.

In practice, groups will typically not prepare a complete set of group GAAP-conformed financial statements for each stand-alone entity. Rather they will draw up the group consolidated financial statements and disclosures based on a large consolidation workings spreadsheet/software, which includes the elimination entries and consolidation adjustments. The higher level of data aggregation and materiality applied may make it difficult to ‘work back’ to group GAAP-conformed financial statements for each entity. As such, various groups are now looking at how their consolidation software and processes might have to change to preserve the required level of granularity.

Data points and sources:

The number of accounting data points needed for the ETR calculations per jurisdiction has been estimated as being more than 200 (depending on the definition used). This data may need to be drawn from multiple different accounting, ERP and tax systems. This is particularly heightened where the group has grown through M&A, meaning that BEPS data warehousing arrangements are getting a lot of attention.

GloBE calculation complexities:

Added to the above is the sheer complexity of some of the GloBE ETR calculation adjustments. For example, for intra-group asset transfers in the transition period historic carrying values will need to be tracked for GloBE base cost purposes. Some MNEs have concluded that a bespoke set of “GloBE financial statements” is the best way to deal with this.

Furthermore, with up to 21 elections on GloBE calculation variations possible per jurisdiction, the complexity quickly ratches up further. Adding further challenges, the February 2023 AG provided that jurisdictions, when designing their QDMTTs, were free to vary to some degree from the GloBE model rules. This included providing for the use of local GAAP rather than group GAAP for local entities. This could well further increase the data to be collected and tracked.

Chinese MNEs are now starting to grapple with all these issues and are waking up to the resource demands this will entail. The more forward-thinking groups are putting together GloBE roadmaps and implementation plans – starting with high level impact assessments, and they progressively move on to modelling and data gap analysis. Building on this, some will already be looking to the need (in certain instances) for group structure modification, potential compensatory arrangements for minority shareholders (who can be impacted in unexpected ways by GloBE tax), and new due diligence and SPA requirements for M&A deals.

A particular area of focus is co-investment arrangements, whether these are business partnerships, joint ventures or other forms. The GloBE rules provide for very different treatments depending on the accounting applied to the arrangements, and such considerations could well play into how they are commercially structured in future.

This is all alongside the fresh look which needs to be taken in respect of currently enjoyed tax incentives; understanding whether they are of value post-GloBE and whether they will be altered by countries, and what new alternatives might become available.

All in all, 2023 is turning out to be a very busy year for tax teams in Asia-Pacific and China because of the GloBE rollout, and will become even more so in the months ahead.

This article serves as a companion piece to a webinar hosted by KPMG China on May 4 2023 which covered the rollout of BEPS 2.0 across Asia Pacific. Click here to watch a recording.