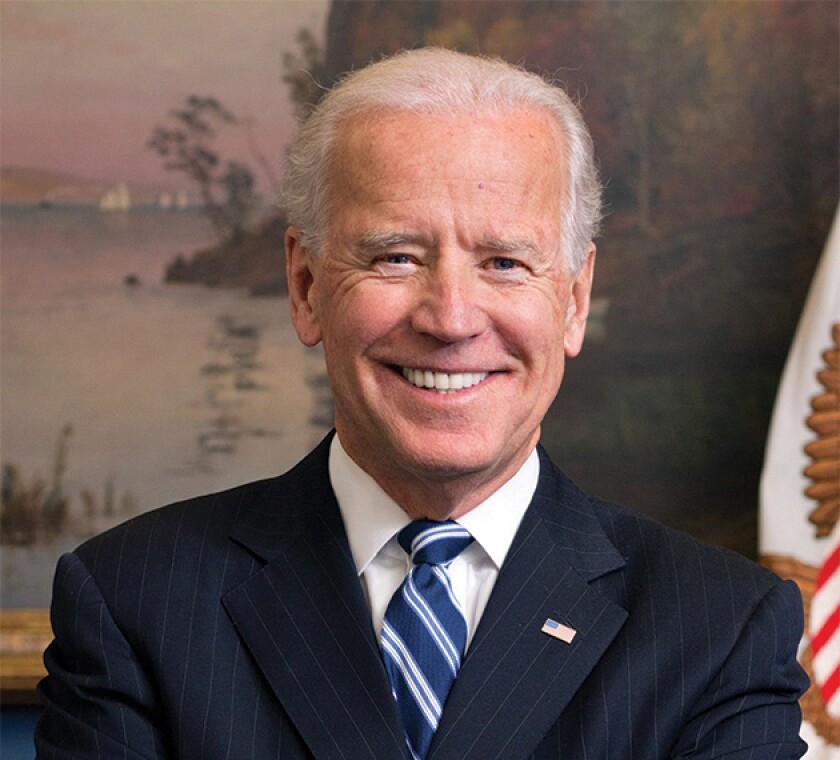

President Joe Biden could guarantee US support for pillar one, but he needs to win another term in office and the Democrats need a strong majority in the Senate first. However, the politics of the US signing up to a fundamental shift in taxing rights is a big question for Democrats as well.

The Republicans could easily portray Democrat support for pillar one as giving away US taxing rights, even though the US may have more to lose if it ends up the outlier in a new global order. A Republican administration could simply choose to throw out the minimum tax and oppose the OECD’s reforms.

Manal Corwin, director of the Centre for Tax Policy and Administration at the OECD, acknowledged there has been speculation about US support for the two pillars at the Paris talks this week.

“There’s been a lot of discussion and speculation about the prospects of ratification in the US,” Corwin told the Financial Times. “But that is the third milestone [after the MLC is finalised and signed] and our approach and our view is we need to get to the first two for that last one to be relevant.”

She added that there was “significant, broad-based agreement to the statement”. Even so, Corwin was clear there were a few key issues to be resolved before pillar one is complete.

Attendees at the OECD talks in Paris this week are right to be concerned about US support for the two-pillar solution. The Inclusive Framework may have agreed an outcome statement on Tuesday, July 11, but this process is vulnerable to the whims of powerful countries.

Not only is the US Congress in a political gridlock, there may be little hope of this changing until the 2024 elections. President Biden is hoping to secure a second term but Donald Trump is determined to make a comeback.

The US has still not implemented pillar two – even though it has a 15% minimum tax rate in place – and this leaves its tax base vulnerable. As more countries impose pillar two, US companies may end up paying more tax in such jurisdictions and not in their own country.

Waiting for America

It’s nothing new that OECD policymakers must carefully consider dynamics in US politics. The Paris-based organisation has been able to build multilateral policies around US positions in the past, including the Common Reporting Standard (CRS).

Under President Barack Obama, the US implemented the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) in 2010. The official aim was to reinforce tax collection and compliance. However, the US policy was at odds with international attempts to increase financial transparency.

US opposition to sharing the information amassed through FATCA meant that the OECD needed an alternative. The result was the OECD designed the CRS to enact the automatic exchange of information everywhere outside the US to complement FATCA.

Almost a decade later, the OECD moved to use the global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) rules as a model for minimum taxation, just as it had taken FATCA as the blueprint for the CRS. This is smart politics. If a lack of American support is a problem, making the US standard international may be the answer.

Likewise, the Centre for Tax Policy and Administration saw an opportunity in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the most radical reform of the US tax code for 30 years. No one predicted that the TCJA, which was signed into law in December 2017, would lead to a global minimum tax rate.

Trump’s radical tax plan established the GILTI rules and the base erosion anti-abuse tax (BEAT). These provisions brought back an old idea in US tax policy: minimum tax rates.

The TCJA may have established the BEAT and GILTI rules in 2018, but it could not have guaranteed full alignment with the two-pillar solution years before that came to fruition. Once in power, Biden built on the TCJA to introduce a higher minimum rate of 15% as part of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act.

With US backing, the OECD was able to secure an international agreement in October 2021 on the pretext of stopping unilateral measures targeting tech companies like Apple and Google. In the end, the two-pillar solution got the support of 137 countries.

Although Biden built on the Trump tax plan, the Republican campaign will most likely frame taxes as a major burden to be lifted off the shoulders of businesses. The Republicans may have supported minimum taxation in the Trump years, but this is no guarantee of support for further reform.

Even though the GILTI rules were the model for minimum taxation, the profit allocation rules go much further than anything in US tax law. New taxing rights may make sense to technocrats in Paris, but not populists in Washington DC.

Biden could win again only to preside over a weak majority, or, worse, a divided Congress. Four more years of political gridlock could dent any hopes of the US adopting the two-pillar solution in full. As a result, the OECD may have to find more compromises that set the reforms back years.