Investment is the engine of growth.

A permanently high corporation tax (CT) rate could severely damage future investment into the UK and stifle homegrown entrepreneurship at a time when this country needs both desperately.

Is there an alternative? Perhaps our nearest neighbour provides the perfect example.

Let’s look at Ireland’s experience of a long-term tax strategy and a lower corporation tax environment and compare it to the UK.

The Irish economy is approximately a sixth of the size of the UK. Yet CT receipts (despite coming off a rate of 12.5%) are a fifth of the UK with its much higher rate of 25%. And there are plenty of other benefits to the Irish economy in the form of VAT and income tax receipts associated with a boost to spending and job creation.

Ireland now has a substantial budget surplus hence talk of their own sovereign wealth fund – putting money aside for a rainy day.

The Irish government has taken a clever approach to international tax reform by being early adopters of a number of the BEPS action points while at the same time continuing to firmly defend their 12.5% CT rate internationally.

The positive effect this policy has had on foreign direct investment (FDI) is clear to see, with over 80% of the Irish CT receipts being attributed to foreign-owned multinationals and those companies estimated to be responsible for 20% of all private sector employment.

In particular, Ireland seems attractive to the US market with over 50% of new FDI projects coming from the US in recent years, a much higher ratio than other European countries.

This is in stark contrast to the situation in the UK.

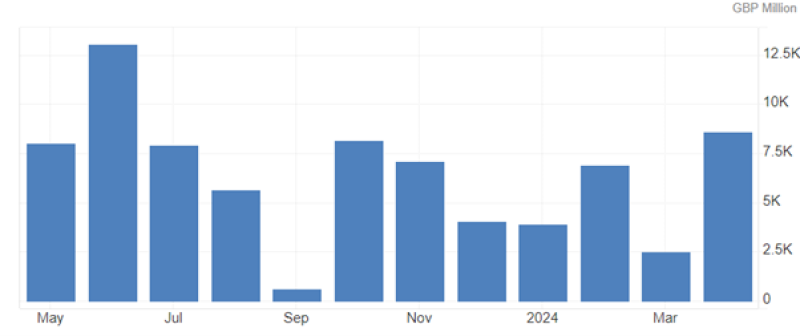

We have a public sector and public debt at a record size, paying out interest month after month (of £4 billion [$5.1 billion] in December 2023 alone) to service that debt.

The UK Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has forecast that taxes and social contributions will rise from 36.3% of GDP in 2023/24 to 37.1% of GDP in 2028/29, which would be the highest level since 1948.

Sadly, the OBR only publishes forecasts of what would happen if the government increased CT, not if they reduced it.

It’s a shame, because even with Brexit, the UK is a very appealing place to invest in, with our user-friendly regulatory and business startup regime, educated English-speaking workforce and our position as the gateway to Europe.

Yes, we’re winning some small one-off battles, with the government proudly announcing new investments in various parts of the country, but the holistic picture is still a flat one.

The CT rate means that we are not harnessing our true potential – remember that the OECD recommended minimum rate is just 15%.

Let’s look at what happened when the CT rate was cut rapidly by the Conservative Party: from 28% when the party came to power in 2010, to 19% in April 2017. Corporation tax receipts, even after adjustments for inflation, ended the decade slightly higher than they started (rising from 2.5% of GDP in 2007-08 to 2.6% of GDP in 2018-19).

Why? Because as the economy grew (partly as a result of these tax cuts), there were more corporate profits, and more companies were created, and more CT was paid.

In March 2021, Rishi Sunak – who was chancellor then – announced a rise in CT to 25%. He said companies should pay more because they'd received so much support from the government during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was always designed as a short-term move in a frantic attempt to get some revenue through the door to pay for the cost of lockdown.

That’s over three years ago – it’s now time to move on. Even though the rise in the rate has brought higher CT revenues in the short term, the price is not worth paying in the medium to long term.

As the Irish experience has shown, a lower UK corporation tax rate would mean far more investment in the UK (including ironically some companies who are currently investing in Ireland). This certainly does not suggest the UK economy will suffer.

Far from it. That uptick in investment will mean more jobs and more wealth creation which will mean higher receipts from personal and indirect taxes which will easily exceed any decline in corporation tax revenues.

The Laffer curve may not be in fashion as much as it used to be, but its central premise still holds true: there is an inescapable link between tax rates and tax revenue. A high CT rate deters investment and reduces tax revenue.

Our research (based on previous changes to the UK CT regime and the Irish model) suggests that a gradual reduction in the CT back to 19%, and then potentially down to 17%, could lead to a significant overall increase in the tax take – perhaps as much as £20 billion. This would be in addition to all the ancillary benefits a revitalised UK economy could bring.

It’s surely something a future chancellor should look at?

UK interest payments on government debt

Source: ONS, Trading Economics