Transfer pricing of transactions involving intangibles is complex and disputes have often arisen. The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations (the OECD Guidelines) recognise the difficulty in identifying factors relevant for pricing intangibles. They note, further, that insiders (e.g., management under the employ of the taxpayer) are uniquely positioned to be best informed (paragraph 6.186). But what if these insiders are no longer available when a dispute arises?

Disputes centring on transaction delineation can be observed in several recent court cases, including one from Germany and one from Israel. For example, one party may view certain facts as most relevant and conclude that a transaction constitutes a certain form; e.g., a sale. Another party may view a different set of facts as more relevant and conclude the transaction constitutes a different form; e.g., a licence.

The definition of intangibles in the OECD Guidelines is broad, and there is no requirement that intangibles be separately identifiable for a transaction to create a payment obligation. Therefore, for all such cases a clear and detailed delineation of the intragroup transaction is needed if an arm’s-length transfer price is to be determinable.

Properly delineating and documenting the relevant facts is, therefore, critical in supporting the transfer pricing if a dispute were to arise. Preparing documentation – in the form of intragroup contracts and supporting evidence files, on a contemporaneous basis when the facts and commercial background are live – is likely to be helpful, when and if tax authorities later enquire. Another way of viewing this documentation: it tells the story of how the transaction and its pricing met the arm’s-length principle at the time the decisions were made and the key commercial events were happening.

Intangibles creation in the context of multinational enterprises

Preparing adequate transfer pricing documentation for intragroup transactions is particularly important with respect to intangibles. Corporate value chains evolve constantly to optimise intangible creation as intangibles are increasingly important in corporate wealth creation. According to McKinsey research, high-growth companies globally invest 2.6 times more in intangibles and grow 6.7 times faster.

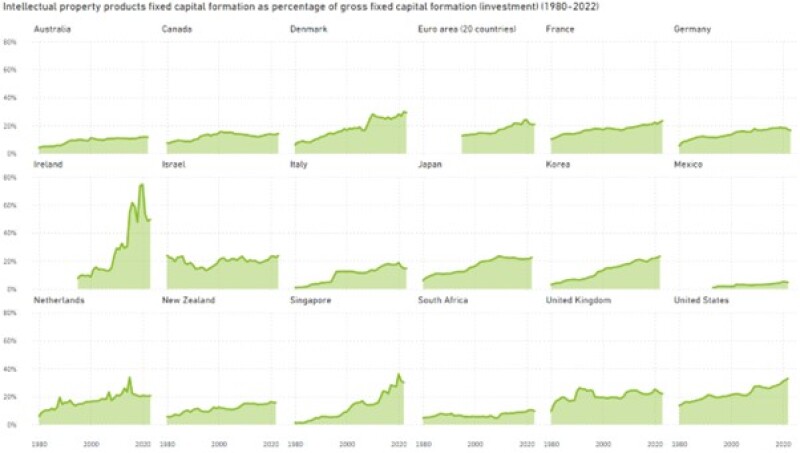

Across the globe, the share of investment (or gross fixed capital formation, in the OECD’s parlance) is increasingly allocated to intangibles. The chart below, from OECD annual data available for selected countries, shows the share of total investment allocated to intangible assets (including R&D, mineral exploitation and evaluation, computer software and databases, artistic products, and related products). This indicates a positive trend, signifying an increasing investment share for intangibles, in multiple countries. We see, for example, the Netherlands increasing the share of total investment in intangibles from less than 10% to more than 50% in 20 years, and the US over that period increased by 10 percentage points. Singapore, the UK, and Denmark are other countries with fast growth in the share of investment for intangibles.

Data source: OECD (OECD Data Explorer • Annual GFCF by asset)

Corporate activity around this investment is dynamic, with internal restructurings, mergers, acquisitions, consolidations, and expansions. Corporate dynamism leads to intragroup restructurings for varied reasons, including the capturing of synergies, undertaking new business strategies, focusing on new markets, refocusing on old markets, and reorganisations to align management activity with value creation. Associated with all of these, intragroup transfers of intangibles are continuing apace.

Transactions involving intangibles – especially when part of a restructuring, when asset ownership is realigning – often attract interest from multiple stakeholders. This is especially the case when intangibles have a central role in a business, C-suite managers are interested, as well as tax and finance groups, along with sales and operations.

External auditors commonly ask about changes in a business, including internal changes. Tax authorities are particularly interested when the transactions involve changes in taxable profit levels. Documenting the multiple decisions taken in relation to intangibles transactions, amid the dynamic business environment, is useful for telling the story to internal stakeholders as well as external.

Application of the arm’s-length principle requires a clear transaction delineation

When identifying the conditions and economically relevant circumstances for intangibles transactions, the OECD Guidelines recognise as particularly important their context within the group and their role in value creation (paragraph 6.3). This is becoming more relevant as intangibles are increasing in value and importance, and as value chains evolve.

This corporate dynamism often manifests itself in what the OECD Guidelines call “business restructurings”. A restructuring may comprise transferring “something of value” or terminating or substantially renegotiating existing arrangements (paragraph 9.10). The OECD Guidelines later offer that “something of value” may comprise an asset or ongoing concern, which is later referred to as “activities” (paragraphs 9.39, 9.48, and 9.68). For a transfer price to attach to the business restructuring, the question is whether independent parties in comparable circumstances would agree to pay in exchange for the transfer or for the contract termination or renegotiation. Business restructurings may result in a change of profit expectation, but that alone does not create an obligation to pay (paragraph 9.39).

A business restructuring necessarily involves a number of economically relevant circumstances. At a minimum, multiple managers and entities have to agree to new intragroup contracts. Documentation reports, in addition to these new contracts, provide a chance to record the economic rationale for why decisions were made.

Some recent court cases demonstrate the challenges with telling this story amid corporate dynamism. It can be seen that in these disputes, different conclusions were drawn by tax administrations and taxpayers with respect to the facts relevant to the intangibles transactions.

German case

On July 17 2024, the tax court of Lower Saxony published a decision related to transactions occurring as part of a corporation’s internal restructuring (more details on this case are available on Deloitte’s Tax@Hand news and information resource). The company, headquartered in the US, consolidated its European management in Switzerland. German subsidiaries had been engaged in manufacturing and distribution. A related party in France had been performing a management role with respect to the German operations, and this management function was consolidated in the Swiss related party.

The restructuring comprised a series of intragroup contracts, with the new contractual terms characterising the German subsidiaries as bearing less risk and the resulting transfer pricing limiting their earnings volatility, with such volatility flowing back to Switzerland after the restructuring. This reduction in risk may have resulted in a reduction in profit potential for the German subsidiaries if it could be demonstrated that independent parties in comparable circumstances would only have agreed in exchange for payment.

Therefore, a feature of the case is the delineation of the transaction, where the below questions were considered:

Did something of value transfer for which compensation would be due?

Had any intangibles been transferred out of Germany to cause this reduction in risk and profit potential?

Does a change in risk profile have to be associated with a change in asset ownership, such as customer information?

Did a function leave Germany, since the Germany operations would henceforth be managing less risk?

The case was decided in favour of the taxpayer as it was determined that neither tangibles nor intangibles were transferred and there was also no transfer of a concrete business opportunity that may qualify as an intangible. The court determined that just because the risk and profit profile changed, and in the absence of evidence showing that an asset or a function had actually transferred, there was no transaction for which arm’s-length parties would have made payment.

We have not heard the last word on this delineation, as a higher court in Germany is considering an appeal.

Israeli case

A 2023 case in Israel also arose in a restructuring context (more details on this case are available on Tax@Hand). A US company acquired an Israeli company. The US company began using the intangibles of its new subsidiary, while also making use of the subsidiary’s existing R&D capabilities. The transactions were delineated as a licence of intangibles and the performance of services, respectively, for these transactions. Accordingly, the licensee paid a percentage of sales as royalty, and the service provider received a service fee comprised of its services costs plus a markup.

The Israeli tax authority’s position was that this arrangement was properly delineated as a sale of intangibles to the US company. Once the Israeli company became part of the US multinational group, it was no longer acting as an owner of the intangibles but was more akin to a subcontractor, and, therefore, the intangibles transaction was, in substance, a sale.

Again, a feature of the case is the delineation of the transaction, where the below questions were considered:

If the transaction is characterised as a licence, and the contract is termed a licence but can be seen as a sale, then is it actually a sale?

If a company has reduced its role in controlling intangibles, does that constitute a disposal of ownership?

The court concluded that the transaction’s form was that of a sale because the Israeli company was allowing its parent to use the intangibles for almost its entire economic life. Furthermore, the court concluded, the subsidiary was acting as if it had disposed of ownership because it was no longer acting to manage risks and protect the intangibles.

The key questions for taxpayers to consider

In the German and Israeli cases, we see taxpayers concluding the form of transaction based on their interpretation of the relevant facts. The tax authorities then concluded an alternative delineation was more appropriate and a different transfer price would attach. The questions asked of the courts are the types of questions the documentation should answer with regard to transactions:

What are the relevant assets subject to the transaction and their respective legal ownership profiles?

What were key employees doing before and after the executing the transaction?

Why is the selected delineation more appropriate than plausible alternatives?

While the German and Israeli cases were decided in 2023 (with the German case published in 2024), the transactions at dispute originated in 2011 and 2009, respectively. This significant time lag shows the importance of contemporaneous documentation that describes conditions and economically relevant circumstances prevailing at the time decisions were made.

The OECD investment data shows that the nature of corporate investment is dynamic, with increasing amounts of capital going into intangibles. Meanwhile, businesses and value chains evolve in support of these investment trends. By the time tax authorities review these transactions, businesses would likely have shifted focus to their latest opportunities. If the relevant facts had not been documented, then when the tax authority commences its enquiry, the next best source would be the memories of employees, some of whom may have moved away from the company in the interim, so may not be available.

As businesses evolve, and as companies continuously seek to ensure an alignment of value-creating activities and transfer pricing, a comprehensive explanation of the transaction delineation supported by written documentation and the associated evidence is critical.

Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (DTTL), its global network of member firms, and their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte organization”). DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) and each of its member firms and related entities are legally separate and independent entities, which cannot obligate or bind each other in respect of third parties. DTTL and each DTTL member firm and related entity is liable only for its own acts and omissions, and not those of each other. DTTL does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about to learn more.

This communication contains general information only, and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (“DTTL”), its global network of member firms or their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte organization”) is, by means of this communication, rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your finances or your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser.

No representations, warranties or undertakings (express or implied) are given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information in this communication, and none of DTTL, its member firms, related entities, employees or agents shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage whatsoever arising directly or indirectly in connection with any person relying on this communication. DTTL and each of its member firms, and their related entities, are legally separate and independent entities.

© 2024. For information, contact Deloitte Global.