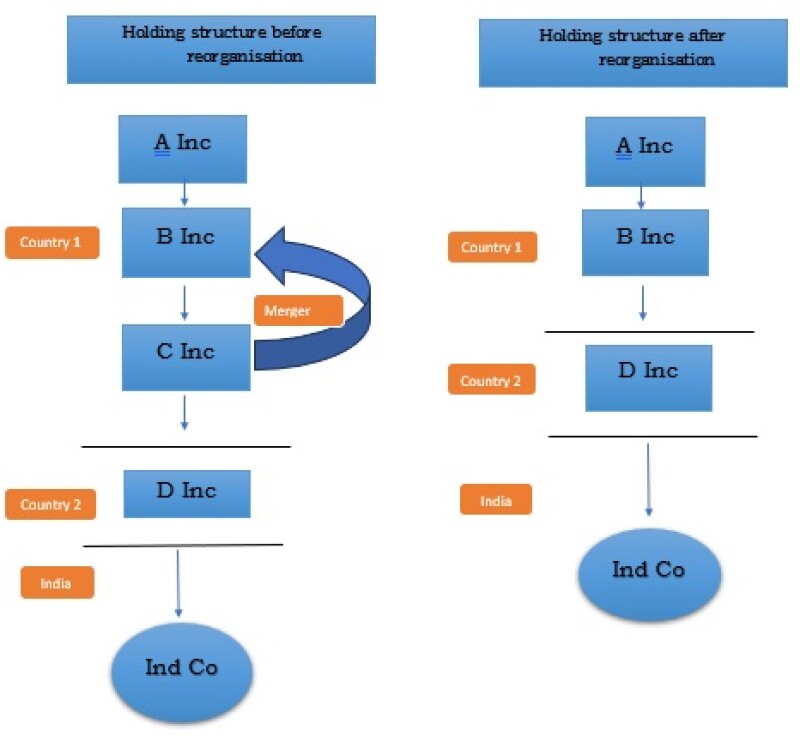

Many large multinational businesses have several layers of holding companies. When the need arises, the layers are collapsed, either to simplify the holding structure, to achieve financial consolidation, or to streamline regulatory compliance.

The Indian Income-tax Act, 1961 (the IT Act) taxes gains arising on the transfer of a capital asset situated in India (Section 45(1), the IT Act). The shares of a company are always located in the country of their incorporation (see Vodafone B.V. v Union of India and Anr (2012), Supreme Court of India). However, by a deeming fiction introduced in 2012, the share of a foreign holding company of an Indian subsidiary is considered as situated in India (Explanation 5 to Section 9(1)(i), the IT Act) if the share of the holding company derives its value substantially from assets located in India (indirect transfers).

Indian courts have held the exchange of shares in an amalgamation as a taxable ‘transfer’ (see Commissioner of Income Tax, Cochin v Grace Collis and Ors (2001), Supreme Court of India). Though exemptions are granted to possible tax liability in a business reorganisation, the conditions attached to the exemption may raise unique questions in certain situations, as in the example below.

Let us assume that the shares of the subsidiary companies are the only asset of these companies. When C Inc amalgamates into B Inc, the shares of Ind Co are not transferred. Applying the indirect transfer fiction in the IT Act, the shares of A Inc, B Inc, C Inc, and D Inc would be deemed to be located in India, and, consequentially, their transfer would be taxable under the IT Act. Furthermore, Section 50CA of the IT Act deems that the market price of the shares of D Inc shall be the consideration arising on such indirect transfer.

Thus, on a plain reading of the IT Act, the following tax liabilities may arise:

On C Inc – shares of D Inc transferred from C Inc to B Inc; and

On B Inc – shares of C Inc would be cancelled.

Let us now look at the exemptions that may be claimed under the IT Act to neutralise the tax impact on the above transactions.

Statutory exemptions for certain amalgamations

Section 47 of the IT Act, inter alia, exempts gains arising on “amalgamation” (both the amalgamating company and the shareholders), subject to certain conditions.

C Inc – Section 47(viab) of the IT Act

An exemption is granted to C Inc subject to two conditions:

The amalgamation should be tax exempt under the laws of the country of residence of C Inc; and

At least 25% of the shareholders of C Inc should hold shares in B Inc post amalgamation.

The second condition is incapable of being met when a subsidiary company merges with the holding company, as B Inc (the amalgamated company) cannot hold its own shares. Thus, it can be argued that the exemption can be claimed by B Inc without meeting the second condition. Support for this argument can also be drawn from an amendment to the definition of ‘amalgamation’ (presently in Section 2(1B) of the IT Act) carried out in 1967 (Finance (No. 2) Act, 1976, read with Circular 5-P dated 09-10-1967).

Also, the maxim of lex non cogit ad impossibilia, which translates to “the law does not compel the impossible”, will squarely apply in the present case. Interestingly, the Authority for Advance Rulings (AAR) has applied this principle in a few rulings to grant an exemption to companies in a position to B Inc.

If the Section 47(viab) exemption is denied

Even if the exemption is denied, it can still be argued that the transaction is tax free. C Inc ceases to exist upon amalgamation, and its identity merges completely with B Inc. C Inc receives no consideration for transferring its shares. In the absence of any consideration, a position can be taken that no capital gains would arise.

B Inc (sole shareholder of C Inc)

Section 47(vii) of the IT Act exempts the shareholder of an amalgamating company, subject to the resulting company being an Indian company. This condition would not be fulfilled in the situation considered herein.

Even before the introduction of the exemption, the courts (Finance (No. 2) Act, 1976, read with Circular 5-P dated 09-10-1967) have held that no taxable gains arise on amalgamation of a wholly owned subsidiary with the parent (albeit on the amalgamation of Indian companies), for the following reasons:

B Inc does not receive any consideration in lieu of such extinguishment of shares. This was based the decisions of the Supreme Court of India in R M Amin (1977) and Madurai Mills (1973).

Even if any consideration was received, the transaction had to be excluded from the operation of Section 45 in view of clause 47(vi)/(viab).

Consequently, the corporate veil ought to be lifted and there could not be any element of gain or loss when a holding company merely rearranges its capital base – it assumes direct control of the capital instead of keeping it in the control of its subsidiaries. However, this argument is highly litigious, as the courts allow lifting of the corporate veil only in exceptional circumstances (Life Insurance Corporation of India v Escorts Ltd. & Ors (1986), Supreme Court of India; Balwant Rai Saluja v Air India (2014), Supreme Court of India).

Benefit under tax treaties

Gains from the alienation of shares in a company located outside India will be taxable only in the state of residence of the alienator under most of the tax treaties entered into by India, except for a few, such as that with the US (Article 13 of the India–US double taxation avoidance agreement provides that each contracting state may tax capital gains in accordance with the provisions of its domestic law). The deeming fiction introduced in Indian domestic law to tax indirect transfers will not automatically extend to tax treaties (Sanofi Pasteur v Union of India (2013), Andhra Pradesh High Court).

Furthermore, if country 1 in which B Inc is located has a tax treaty with India, it may avail the non-discrimination clause and claim the exemption available to Indian companies in Section 47(vii) of the IT Act. The AAR has accepted a similar claim in a case that involved the India–Italian tax treaty (Banca Sella S.p.A. (2016), AAR).

Key takeaways on the Indian impact of overseas businesses reorganisations

Overseas business reorganisations may have tax ramifications in India, even without involving any direct transactions in the shares of the relevant Indian subsidiary. A careful examination of the transaction is required from the perspective of Indian domestic law and with regard to tax treaty provisions. Taxpayers need to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of various positions and safeguard themselves against any potential challenges from the tax authorities in the future.