The term 'digitalisation' is much like beauty – its meaning is in the eye of the beholder. This is even more evident when using the terms 'digitalisation' and 'tax' together, which can reasonably mean different things to different people, depending upon the precise context in which those words are used.

The term 'digitisation' refers to the taking of analogue information and encoding it to a digital form (for example, into zeroes and ones), so that computers can store, process and transmit such information. By contrast, 'digitalisation' refers to what happens to processes, with the digitisation of information facilitating this as a supporting step. Digitisation is seen to have been taking place for decades, whereas digitalisation is seen as relatively new.

By way of illustration, 'digitalisation' and 'tax' can refer to the way in which technology is deployed in managing tax obligations; it can refer to the ways in which digital economy businesses are impacting upon tax collections; and it can also refer to the ways in which tax administrators are advancing their digital agenda.

This article seeks to explore each of these themes and, most importantly, how they converge.

The inspiration for this article came from a KPMG colleague, who recently put forward this view in an informal discussion: "In the end, interpretation and judgment by the human brain will always be smarter than artificial intelligence". He was putting forward a view espoused many times by tax professionals, to the effect that there will always be an important place for judgment, for experience and for empathy, alongside knowledge in the management of tax functions.

As we plot a path to the future, the authors' wish to posit this question – what if tax rules and regulations and their administration change to such an extent that judgment, experience, empathy and knowledge diminish in their relevance? In other words, when we contemplate the future, we need to consider the impact not only of technological advances, but also developments in tax rules, regulations and their administration which will become increasingly digitalised.

A short example may be used to give this context. The authors were recently shown a demonstration of a technology product called the 'Tax Intelligence Solution'. This solution allows businesses to track their permanent establishment risk by reference to data and analytics carried out on transaction level data collected through a company's enterprise resource planning (ERP) system. What made this demonstration particularly interesting is that its creators had sought to reduce complex and somewhat nebulous concepts of permanent establishment to a series of data points. And then it dawned on us, if technology solutions can be developed to test complex concepts such as permanent establishment with a reasonable degree of accuracy, why should we not expect tax legislation to similarly evolve so that taxes are actually imposed by reference to data points? And even then, it's not difficult to foresee a step change to actually imposing those taxes on a transaction level basis. Corporate taxation, in its existing form, would be dead – a theme we revert to a little later.

This article is deliberately provocative, and whether readers agree or disagree with its conclusions, it is simply hoped that it inspires tax professionals to critically think, to challenge the status quo, and to start to change their future. To those readers who prefer to keep doing 'the same old thing', the future of the tax profession may therefore look rather grim (if indeed the future is correctly predicted here). However, the reality is that many tax professionals enter the profession because they are attracted to its fast-changing nature, and for them the future looks exceptionally bright. The challenge is to cast one's eyes to the future, but then to start now on a journey of self-learning and development.

Before we begin, here are a few key propositions or themes which run through this article:

To understand the future of tax in a highly digitalised world, watch the progress of value-added tax (VAT) since it will guide many of the changes to other taxes too;

The world of corporate tax will be completely upended over the next 10 years as it struggles to adapt to digital economy business models;

In the future most taxes will be imposed by reference to a series of data points, designed to replace many forms of decision-making; and

The challenge for the modern tax professional (whether working in an in-house or external role) will be to manage the data, identify any discrepancies or trends, and gain control and draw insights from it.

Let's explore these key themes now.

How things were 20 years ago

The famous quote that "history is the best guide to the future" (Bill Dedman) is the starting point for our journey. So let's look at how things have already evolved over the past 20 years or so.

Twenty years ago, libraries in professional services firms maintained looseleaf services in which tax professionals could look up legislation, recent case law and commentary on what the law meant. The information was stored in a 'looseleaf' service because the librarian could literally remove a 'leaf' or page from the book and replace it with a new page, as legislation, case law and commentary was updated. These updates typically occurred every three months or so, meaning that the 'most recent' changes were in fact about three months old.

Email was still relatively new, and telephone, facsimile and couriers delivering letters were the dominant means of communications with clients.

By and large, most tax advice given to clients consisted of looking up the relevant provisions and applying them in a straightforward simplistic way. In a sense, we had information which our clients did not possess. They paid us for this information.

Businesses were reasonably straightforward. Globalisation had yet to fully emerge, so most business models were domestically based, and they all had a physical office or factory or other permanent establishment from which they operated.

Progress over the past 20 years

Major developments in technology have already transformed the tax profession over the past 20 years, yet many of us do not even recognise them.

Take the earlier example of clients merely paying for access to information. Already, that has largely ended. The tax professional's role has quickly transformed such that we are paid for insights, for our experiences and for our professional judgment. The idea of simply passing on information ceased with the advent of the powerful search engines such as Baidu or Google. Put simply, those search engines gave clients the ability to access that very same information. However, understanding what that information means and how to apply it, has been the most recent wave of progress.

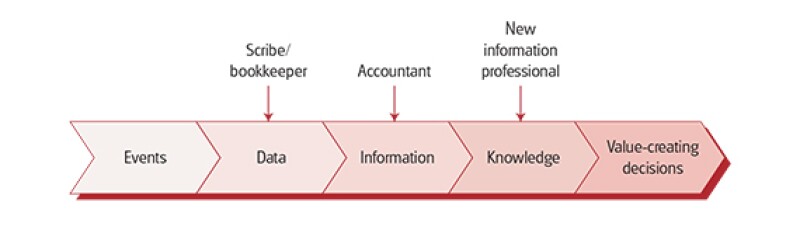

The progress chart in Figure 1, which dates back to a 2002 article in the American Accounting Association journal (by Elliott & Jacobson, entitled 'The Evolution of the Knowledge Professional'), provides a good overview of the evolution that has taken place in the accounting profession.

The speed of these developments has been hastened by tax authorities too, given the vast amounts of information they make available online. Whereas previously, such information could only be 'learned' through actual experiences, now tax professionals can often ascertain the local practices of tax authorities across China simply by the click of a button. In short, information is now more freely available and therefore more 'free' than ever before.

Figure 1

How things are today

As we have seen, the tax profession has already changed considerably in ways we rarely take the time to notice, with the major change being the way in which our clients consume information. Here when we refer to 'clients', they may comprise either the external customers of our organisation, or the internal stakeholders who rely upon our work.

Both of these categories of client are typically now less prepared to seek technical advice than they did previously. There are several theories which may be posited to explain why clients are now less prepared to seek such advice, including:

In many developed countries, from the 1980s, there was a shift to 'purpose-based' tax rules. This saw the move away from literal interpretations of tax law, encapsulated in what is commonly known as the 'Duke of Westminster principle' (which allowed for greater certainty, but facilitated tax planning) towards more purposive based approaches. This was paralleled by many countries adopting general anti-avoidance rules. These developments resulted in less certainty in tax advice.

A further development was the internationalisation of business, which brought with it the potential for greater instances of double taxation and disputes. Given that the main means of mediating these issues was through transfer pricing – a body of tax which is based on economic analysis that can be argued for and against without any single source of truth – this also introduced further uncertainty.

The influence of accounting standards and tax provisioning, with probabilistic elements feeding into arriving at tax numbers, has also played a role in bringing the focus down to 'the number'.

Additionally, the speed of tax rule changes across countries also means a more confusing and less stable tax environment.

To the extent also that activities in emerging economies became more central to the operations of multinational companies, the fact that tax practices in many of these countries are based less around the law and more around local practices, a technical opinion also came to have less value.

Ultimately then, it might be said that a number of factors has contributed to undermining the possibility and relevance of legal certainty, and has led clients to a greater focus on probabilistic outcomes, with consequent implications for the assistance they seek from both in-house and external tax advisors.

This has led to a much greater tendency for clients to want 'just the answer'. In other words, they see tax decisions as coming down to the question of whether to put a number in a box on a tax return (or not). Uncertainties, assumptions and facts are merely hurdles to be overcome in this quest.

The next big trend, which is only really beginning to emerge now, is around benchmarking, where clients want to understand how they are positioned relative to others. Instead of asking what they should do, clients are now more likely to ask 'what do others do?' It is no coincidence that the rise of benchmarking has mirrored developments in how tax authorities manage risk too – increasingly they look for statistical outliers and then they use those as the basis to raise queries and to carry out audits and inspections. Expect this wave of benchmarking to continue for many years to come, simply because it is one form of data and analytical testing, which we explore further below.

A related issue is whether we have already reached the high watermark of tax authority cooperative compliance approaches with taxpayers. Over the past five to 10 years, these cooperative compliance models have benefited tax authorities in facilitating greater levels of voluntary compliance, and thus allowed tax authorities to dedicate their limited resources to other higher risk taxpayers. But in a data driven world of today (and tomorrow), what if the tax authorities no longer need our cooperation? What if they know the problem before we do? By way of example, in Brazil the tax authorities are nearly approaching this point through tax and accounting data which is fed into the 'SPED' system, with discrepancies between actual and expected results triggering taxpayer queries. Along similar lines, Poland has just announced that it will eliminate VAT returns because they will already have all of the data through the SAF-T reporting system.

Interestingly, while these developments have emerged over some time, curiously, when it comes to how we manage tax compliance obligations, progress over the past 20 years has seemed far more muted.

For example, many in-house tax professionals continue to obtain data from the company's ERP systems and from the Golden Tax System, they prepare reconciliations to that data, they make manual adjustments to scrub, cleanse and generally rid themselves of poor quality content, and then they proceed to prepare endless Excel spreadsheets and work papers which are shared and approved by reviewers. The documents are stored to provide a suitable audit trail in the event queries are raised.

And then those in-house tax professionals do exactly the same thing again the following month: an exercise which typically begins on day 1, and often ends around day 15 (or the relevant filing date).

All of this so that they can file a tax return with a reasonable degree of accuracy. This is carried out either monthly, quarterly or annually for most businesses filing VAT, corporate income tax (CIT) returns, individual income tax (IIT) withholding, stamp duty and other returns.

It hardly seems very advanced or sophisticated, does it?

As noted earlier, there has often been a gap (or in some organisations, a hierarchy) between tax advisory work and tax compliance work. A divide often created because this work has been performed by different people within the same organisation, resulting in very few insights and little analysis drawn from one area into the other. For example, in many large organisations, in-house tax advisory professionals have literally been advisors to the business, in responding to developments and tax issues raised by the business, without always being responsible or accountable for the tax returns and the amount of taxes actually paid. Many of them would argue they have too little assurance and control over the completeness and accuracy of the data driving those tax (filing) positions; with this responsibility often resting with other business functions. Separation and lack of ownership over tax compliance by tax advisory functions within an organisation is difficult to justify in a data driven world.

This will change, and this will surely be the hallmark of the next 10 years or more in the tax profession.

Put simply, tax compliance work will become very highly automated; it will become highly data driven; with data and analytics technology providing insights from that compliance work so as to drive the agenda for tax advisory work. The era of tax automation and digitalisation is just beginning.

And then the world changed

Now let's wind forward to the year 2040. Imagine ourselves sitting in our self-flying autonomous vehicles (because why limit ourselves to the road when there is a whole dimension called airspace we can occupy) and ponder this. We are telling our grandchildren about what we did in the olden times just over 20 years ago. We tell them about how we prepared tax returns back then and they laugh at the ridiculously inefficient and quaint way in which it operated. They chuckle at the extent of trust which underpinned our tax systems, at the enormous workload and manpower required to administer it, and of these funny things called invoices or fapiaos.

And then we tell them this is what we all did for a living, before one of the gigantic technology companies (we are not going to predict who), decided to disrupt the tax system once and for all.

This gigantic technology company figured that because they owned and controlled most of the world's transaction infrastructure, either through their platforms, their payment processing capabilities, or their cloud storage facilities, that they could automatically construct tax returns from transaction level data, automatically divert the funds from the proceeds of those transactions so that tax could be calculated, determined, inspected, audited and paid in real time. They did this not only for VAT, but they also developed transaction level analytics for CIT purposes, automated transfer pricing adjustments, and remitted IIT withholding on salaries and wages. In short, they built a 'total tax solution' because they owned the data, the infrastructure and controlled the means of payment to enable it, and they charged service fees for providing this valuable tax collection service to governments. Quickly governments around the world seized on the opportunity to reconfigure their tax rules – they recognised that if tax fit the way business was operating they would collect far more than if they maintained their same regimented tax systems which were becoming increasingly obsolete and divorced from a digitised world.

Is this idea far-fetched, or is it feasible? Let's explore this a little further.

It started with a VAT and then it moved from there

In this futuristic world of 2040, we have predicted the (near) total automation of taxation – every aspect from its scope, to its rules, to its collection, administration and enforcement will be digitalised. But it all started with VAT. Let's take a look at how VAT led the way.

Perhaps the most dramatic change to tax systems around the world in recent times has been the growth of indirect taxes. More specifically, VAT and GST systems have grown from being implemented in only a handful of (predominantly) European countries, to now being in over 160 countries around the world. Likewise, the proportion of total tax revenues raised from consumption taxes has nearly doubled from 11.9% in the 1960s to 20.6% in 2015, and the average VAT rate among OECD countries has now increased to 19.2%, based on data produced by the OECD in its 2016 Consumption Tax Trends.

In a typical supply chain in which a manufacturer supplies goods (or components of goods) to a wholesaler who in turn supplies finished goods to a retailer who then supplies to an end consumer, a traditional VAT system would produce the following outcomes:

Three separate parties accounting for output VAT (the manufacturer, the wholesaler and the retailer), with only one of those parties (the retailer) raising any real revenue. The government is effectively 'at risk' as a creditor for the payment of the VAT from those parties;

Three separate parties accounting for input VAT (the manufacturer, the wholesaler and the retailer), which again places the government at risk, though none of those parties is the person who is meant to economically bear the tax; and

All of this is done so that when the end consumer purchases goods or services, the VAT which is embedded in the final price they pay is subjected to tax.

By describing in this way how a VAT works should be sufficient to identify its inefficiencies and its potential for technological disruption. However, rather than fearing the demise of a VAT, the authors take the view that it has several features which make it to be most likely to lead the way (among taxes) as we move towards this futuristic world of 2040. Consider this:

A VAT seeks to tax final the private consumption expenditure of goods and services. It is collected from businesses, yet it is economically imposed on end consumers. The fact that it taxes the consumption of goods and services makes it about as certain to continue as any other form of taxation. While supply chains and the ways in which goods and services are manufactured, processed, sold and delivered may be disrupted, consumption is always inevitable;

A VAT is a transaction driven tax. It is relatively more efficient to collect than many other forms of taxation; and

It applies what is known as the destination principle – meaning, that the tax is collected from consumers in the jurisdiction in which the relevant goods or services are consumed.

Each of these features make a VAT far more effective in a digitalised world. Put simply, consumers will continue to consume, and the alignment created by a VAT between a business' self-interest in developing a market for the sale of goods or services and the collection of tax in the place in which those goods and services are consumed, prevents many of the same 'tax wars' which marked the period from 2020 to 2030 (as discussed further below). However, where there is misalignment in a VAT, it is in the process for its collection as described above – which is highly inefficient.

In the near future, VAT systems will evolve to being akin to single stage retail sales taxes which are collected at the point of sale from end consumers, with digital certificates being used to avoid the need to collect and remit on business-to-business transactions. Fundamentally, with these changes, indirect taxes should survive and even thrive as the level of VAT fraud is progressively reduced and the cost of collection decreases. In short, VAT is perhaps already the tax most digital-ready, and the evolution described above will remove the final impediments to its domination.

Why VAT is a useful guide to the future

Now let's look at a few specific examples to support why we say the pathway of a VAT serves as a useful guide to the future of taxation.

The first example is the way in which VAT rules are already being introduced to remove judgment and knowledge, in favour of digitised concepts. For example, in the EU (Council Regulation 1042/2013, Articles 24b(d) and 24f), to determine the place of supply of certain digitised services, the service provider needs to obtain two non-contradictory pieces of evidence about the location of the consumer. In other words, legislators have already recognised that determining the place of supply should no longer be based on nebulous concepts such as the residency of the consumer, or the place of the consumer, or even where the consumer has actually used or enjoyed the supply. Rather, it should be based purely on data points such as the customer's IP address, his/her delivery address, bank details or the country code of the SIM card being used.

Taxation based purely on data points rather than relying upon 'judgment' or 'knowledge' by an individual is, in the authors' opinions, among the next wave of change to sweep through tax regulations.

The second area in which VAT is evolving is in the imposition of liabilities on businesses which do not own the relevant goods or services, but rather, facilitate the transaction through their online platforms. We are referring here to the phenomenon of imposing VAT liabilities on online marketplaces – first introduced in Australia, and shortly to be adopted in places such as the EU, New Zealand, Singapore, and so on – consistently with the work carried out by the OECD's Working Party 9 on Consumption Taxes.

To be clear, the concept of collecting tax liabilities from a person other than the party earning the relevant income or deriving the gain is nothing new. Withholding taxes have worked on this basis for some time. But what makes this VAT phenomenon especially interesting is that liabilities are now being collected from non-resident (suppliers) in preference to collecting the VAT from resident (consumers). Literally the converse of what is ordinarily seen with withholding taxes.

How does this work?

While in its infancy, the underlying or implicit foundation for the operation of these rules is that online marketplaces will account for the VAT as a price for their licence to operate in that jurisdiction. If they fail to account for the indirect tax, they risk tax authority action (at the moment achieved through cooperation between their home jurisdiction and the jurisdiction in which they are transacting), they risk goods being stopped at the border, they risk their platforms being disconnected from consumers in that jurisdiction, but perhaps most of all, they risk reputational damage.

Interestingly, the digital economy was initially seen as a force which would sweep away traditional intermediaries and with it many of the traditional taxing points which could be leveraged by tax authorities for tax collection purposes. However, the recent emergence of online platforms has re-intermediated this activity, and provided a new optimal taxing point for tax authorities.

It does not take a big stretch to imagine tax authorities seeking to expand upon these concepts in requiring VAT to be collected by online platforms for purely domestic transactions too. The obvious attraction for tax authorities lies in the fact that they perceive the ability to better enforce compliance against a small number of large online platforms than to collect and enforce from a large number of smaller retailers.

Along similar lines, several South American countries (such as Colombia, Costa Rica and Argentina) are changing their indirect tax legislation to impose VAT withholding or collection obligations on debit or credit card providers – effectively a form of 'point of sale' tax collection. Similarly, several European countries are trialling the use of split payment methods. Ultimately, with the rise of payment providers or gateways, it would not be difficult to foresee the rise of tax collection taking place from them.

So what does this tell us about the future of taxation?

It tells us to expect the future digitalisation of tax regulations so that our tax rules will increasingly be aligned with digital business models. This may result in the imposition or allocation of taxes being based on fixed or objective data points rather than nebulous concepts. Thus the impetus for better managing data becomes ever more urgent.

Related to this is the belief that 'data managers' will be among the next wave of professionals sweeping through organisations. These are people whose role it is to go beyond motherhood statements around poor data quality; people who can identify the root causes of data problems and define how they may be overcome.

It also tells us to expect more and more taxes to be collected from third parties who merely facilitate or enable transactions. Another way of framing this is to speculate whether 'trust' is being removed from many indirect tax systems in favour of a 'follow the money' approach. Ultimately though, these are merely baby steps in a journey towards real time tax collection, which is expected to take hold once developments in the technology needed to support it evolves.

CIT challenges over the next 10 years

If VAT merely needs evolution to grow over the next 20 years, then CIT will require a revolution.

As mentioned earlier, VAT rules in most jurisdictions (including in China) apply the destination principle. As Professor Rebecca Millar recently noted (in 'The Future of VAT in a Digital Global Economy 2014'), there is a real contrast in the challenge for policymakers dealing with corporate taxes as compared with indirect taxes:

"Yet the conclusion that 'something needs to be done' simply does not have the same significance for VAT as it does for income tax. This is not because VAT on global digital transactions is easy to collect: it is not. Nor is it because VAT raises different collection problems than income tax: for the most part, it does not. What is different about VAT is the almost universal agreement on the substantive jurisdictional principle that should be used to determine the tax base. Some countries might pay lip service to the destination principle, particularly countries with limited tax collection capacity and a high reliance on VAT to meet their revenue needs. Other countries – or their tax administrations and/or courts – might disagree about what the destination principle requires in particular circumstances. Nonetheless, there is little or no significant disagreement on the fundamental principle. Nor is there any significant disagreement about the most important aspect of the neutrality principle, which entails the notion that there should generally be no tax burden on business-to-business (B2B) transactions under a VAT. Thus, whatever it is that needs to be done, it is unlikely to involve a fundamental re-think of the jurisdictional basis upon which decisions are made about which country has the right to tax consumption. [Footnotes omitted]"

For many years, the corporate tax debate has centred on questions of 'residence' or 'source'. Questions around the extent of presence required before creating a permanent establishment were ever-present, and even then, once identified, the focus became one of determining or allocating the profits attributable to that permanent establishment.

With the growth of the digital economy, these concepts are now under more scrutiny and strain than ever before. That scrutiny arises because digital business models create the circumstance in which a company situated in country A can readily supply goods or services and derive profits from consumers in country B, without the creation of a permanent establishment.

There is perhaps no better recent example highlighting this scrutiny and strain than the US Supreme Court's decision in South Dakota v Wayfair Inc 585 US (2018). In that case, the majority of the court overturned settled law which had required the physical presence of a company in a particular state as a prerequisite for them incurring sales tax compliance obligations in that state. The view of the majority judges included the following:

The "dramatic technological and social changes" of our "increasingly interconnected economy" mean that buyers are "closer to most major retailers" than ever before – "regardless of how close or far the nearest storefront." Direct Marketing Assn v Brohl, 575 US (2015) (Kennedy, J, concurring) (slip op, at 2, 3). Between targeted advertising and instant access to most consumers via any internet-enabled device, "a business may be present in a state in a meaningful way without" that presence "being physical in the traditional sense of the term." Id, at (slip op, at 3). A virtual showroom can show far more inventory, in far more detail, and with greater opportunities for consumer and seller interaction than might be possible for local stores. Yet the continuous and pervasive virtual presence of retailers today is, under Quill, simply irrelevant. This court should not maintain a rule that ignores these substantial virtual connections to the state.

While this case was about US sales taxes (coincidentally a form of indirect taxation in which this decision gave effect to its evolution), precisely the same arguments could be made from an international corporate tax perspective too. Yet curiously, nothing similar has been done.

In earlier stages of this debate, the OECD and government authorities focused on identifying the unique aspects of digital business models which enabled this phenomenon of being able to carry on business in one jurisdiction yet earning profits in another (without a physical presence). However, it soon resulted in a fruitless attempt at 'pigeon-holing' digital businesses into particularly types. Moving forward, there is increased recognition that separately categorising digital business models runs the risk of premature redundancy as more and more 'bricks and mortar' companies develop similar features too.

Thus the new debate taking place in a CIT context tends to focus on three main questions:

Where is value being created?

How do we measure (or allocate) the value which is created?

What does this mean for existing permanent establishment concepts?

In very simplistic terms, these questions are really asking about both nexus and profit allocation concepts. These are pretty fundamental issues.

Each of these questions focuses on the debate from a point of principle, and therefore from a theoretical or academic perspective, they are difficult to fault. But are they pragmatic? How would they be implemented by tax authorities in both developed and developing countries? How would they withstand the test of time? How will they be handled by politicians, keen to ensure their country gains a 'fair share' of tax revenue? And how will they be perceived by the general public, eager to ensure increasingly powerful technology companies pay tax in a way which bears a reasonable relationship to the revenues earned in their country?

Rather than set out in detail the academic arguments in this debate, in the authors' views, we consider it likely that pragmatic approaches will prevail. Academic arguments in this area tend to become problematic when one recognises that there are almost as many theories, arguments and positions as there are jurisdictions involved. Each of the academic arguments is seized upon by those seeking to pursue their own country's tax agenda – whether it be to protect their own businesses, or to assert a claim to tax revenue for their citizens. And furthermore, ultimately any solutions must be capable of measurement and implementation.

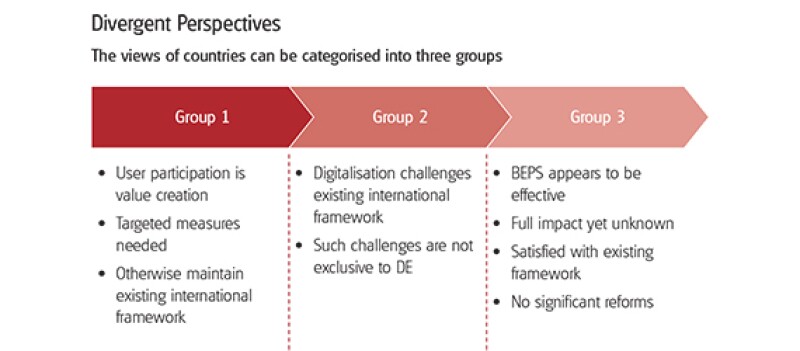

This divergence of opinion is best illustrated by Diagram 1.

The tax 'bingo' game taking place right now involves guessing which country can be assigned to which particular group – an outcome which can fairly easily be determined by asking whether that country is a net importer or net exporter of digital products and services to the world.

In 2018 the OECD attempted to lay forth both short-term and long-term measures to tackle the tax problems arising from the digital economy. The short-term measures, which involved the imposition of digital services taxes did not meet with support, yet has already triggered a first wave of EU countries seeking to go it alone.

Diagram 1

The year 2020 is expected to be a watershed year in the development of tax solutions to the challenge of digitalisation, which coincides with the expected release by the OECD of its final report on the tax challenges arising from digitalisation. Either global policymakers will make a major breakthrough, and arrive at a cohesive framework which somehow binds together the above three disparate groups; or they will fail and countries will go their own way. The end result if an accord breaks down, is undoubtedly double taxation, and perhaps even the beginning of the 'tax wars'.

The Head of the OECD's Tax Policy and Statistics Division David Bradbury was recently quoted (in Tax Notes International, September 10 2018) as saying: "We're under no illusions as to how challenging it will be to reach consensus on these very difficult issues" – perhaps an understatement given that the Group 1 countries recognise the need for change while the Group 3 countries do not, yet the Group 2 countries see the problem as being much broader than that of the digital economy. In other words, there is not even consensus as to the scale of the problem, let alone consensus as to how to solve it.

Interestingly though, Pascal Saint-Amans, OECD director of the Centre for Tax Policy and Administration, is referred to in the same article as speculating that the "debate would shift toward determining how to allocate taxing rights first, then defining a nexus for taxing the digital economy, instead of the other way around". This is the mathematical equivalent of seeking the answer (i.e. the amount of tax to be raised) before knowing the formula (i.e. the policy settings) to arrive at it.

In a pragmatic sense though, the authors agree with Saint-Amans. Countries (and their political leaders) will undoubtedly want to know how much tax revenue they would stand to gain (or lose) before they define the rules used to impose them. However, when it comes to defining those rules, we would speculate that corporate taxes which take on more of a destination basis as part of their tax base, and which are imposed on transactions, will need to prevail.

In the authors' views, destination-based transaction taxes will prevail for the very simple reason that they achieve a greater alignment in the collection of tax and business self-interest than traditional sourced-based taxation rules. However, whether that outcome is achieved through the expansion of permanent establishment rules, through the imposition of digital services taxes, though the imposition of alternative forms of minimum taxation, or even through changes to transfer pricing and profit allocation methodologies remains to be seen. Ultimately though, these are merely the mechanisms which produce the shift to more destination-based transaction taxation – a key feature of which has made the rise of indirect taxation systems throughout the world so effective. The next big challenge would then be to combine a destination-based corporate tax with an indirect tax into a form of super-taxation!

In short, for all of these reasons, we tend to the view that CIT will evolve so that it much more closely resembles indirect taxes in the sense that they will be collected in the place where consumption occurs, and on a transactional basis. Let's explore these reasons:

As noted previously, while the future model is subject to much debate, we do consider that some change will happen. The ability for a company to be located in country A, yet carry out substantial business operations (and earn profits) in country B is well recognised. It may be the model that is being used by many 'pure' digital economy companies, but over time, its extension to areas such as fintech, the healthcare sector, traditional retailers, banks and other financial institutions, even professional services, can hardly be doubted. Thus, the argument for change has an air of inevitability about it.

Both the OECD and the EU have recently issued reports examining the potential introduction of digital services taxes. These taxes, intended to be turnover based, are to be applied to three categories of transactions – advertising revenues, intermediation services and data transmission. Their goal is to collect and impose taxes on digital platforms able to derive substantial revenues (and profits) from consumers in a country without having a physical presence. What is interesting about these taxes is that in economic form they may be regarded as direct taxes, but in substance they rely on indirect tax collection methodologies. That is, in identifying the location of the consumer, the nexus between the type of service provided to that consumer and the revenue earned from that consumer. Jurisdictions such as India, Chile, Uruguay and Taiwan have made early forays into this realm of taxation, closely followed by a number of European countries. So already we are seeing a fundamental shift in corporate taxes to more closely resemble destination-based transactional taxes, applied to gross revenue amounts.

Corporate taxation rates are falling around the world. For example, over 30 years ago we had more than 30 countries with rates of over 50%, yet only five countries have rates at this level today. The argument that something must be done, is again difficult to contend with given these statistics.

What this means for the tax professional of the future

When tax professionals think of the future, they commonly consider the impact that technology will have on tax collection by tax authorities – that is, the 'digitalisation of tax'. Many tax professionals also think about how the broader economy is changing through digitalisation of business models. But what many fail to consider is the likelihood that tax itself will change as a result of digitalisation in the way it is legislated, collected and administered. The idea that taxes will be imposed by reference to various data points recorded in taxpayer systems; and furthermore, the concept that by aligning taxes with transactions in the place or jurisdiction in which the relevant goods or services were consumed, creates the circumstance under which long-term alignment between digital business models and the needs of modern economies. Similarly, at the other end of the spectrum, tax professionals are already being asked to transpose (often formal) tax requirements into data points, so as to automate taxes in their business ERP systems (mainly for transactional taxes). The combination of these factors will produce greater alignment between those tax requirements and clients' data in the future.

Ultimately though, the authors predict the end point of all of this analysis for tax professionals is pretty clear – it may be a cliché but it truly is 'all about the data'. How well do you know your data? How accurate is it? Can you control it? Do you really know how to analyse it? These are the questions every tax professional needs to focus on over the next few years as we embark on the digitalisation of tax.

Lachlan Wolfers |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China 8th Floor, Prince's Building 10 Chater Road Central, Hong Kong Tel: +852 2685 7791 Mobile: +852 6737 0147 Lachlan Wolfers is the national leader of indirect taxes for KPMG in China, the leader of KPMG's indirect taxes centre of excellence; the Asia Pacific regional leader, indirect tax services; and a member of KPMG's global indirect tax services practice leadership team. Lachlan also is head of tax technology for KPMG in China. Before joining KPMG China, Lachlan was the leader of KPMG Australia's indirect taxes practice and the leader of KPMG Australia's tax controversy practice. Lachlan leads KPMG's efforts in relation to the VAT reform pilot programme in China. In the course of this, he has been asked to provide advice to the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the State Administration of Taxation (SAT) and other government agencies in relation to several key aspects of the VAT reforms, including the application of VAT to financial services, insurance, real estate, transfers of a business, as well as other reforms relating to the introduction of advance rulings in China. Lachlan is formerly a director of The Tax Institute, which is the most prestigious tax professional association in Australia. In this role, he was frequently invited to consult with the Australian Taxation Office and Commonwealth Treasury on tax issues, as well as consulting with government officials from both China and the US about indirect tax reform. Before joining KPMG, Lachlan was a partner in a major law firm, and has extensive experience in a broad range of taxation and legal matters. He has appeared before the High Court of Australia, the Federal Court of Australia and the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, including in the first substantive GST case in Australia. Lachlan is a noted speaker on VAT issues and has also presented numerous seminars for various professional associations, industry groups and clients on the VAT reforms in China. |

Vincent Pang |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China 7th Floor, KPMG Tower, Oriental Plaza 1 East Chang An Avenue, Beijing Tel: +86 (10) 8508 7516 Vincent Pang is based in Beijing and the head of tax for northern China. He specialises in providing Chinese tax and regulatory advice. He is focused in serving companies in the TMT sectors but also has extensive experience in serving many companies in the industrial and consumer market sectors. Vincent started his career with professional accounting firms in Canada in 1991 and has experience in various disciplines including tax, auditing and consulting. He arrived Beijing in 1998 and started to focus on providing China tax services to foreign investors in the areas of tax structuring, tax planning, general tax advice as well as tax compliance services. Vincent has also been active in assisting many foreign companies in designing their corporate and operational structures in China to meet their business objectives, as well as many Chinese domestic companies on their pre-initial public offering (IPO) restructuring and outbound investments. Vincent has also been providing individual income tax services to foreign assignees working in China on the structuring of their compensation package as well as senior management of pre-IPO companies on the structuring of the equity plans and investment holding. Vincent is a member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Canada and the Certified General Accountants Association of Canada, and has bachelor's degree in commerce from McGill University in Montreal. |

John Wang |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China 12F, Building A, Ping An Finance Centre, 280 Minxin Road, Jianggan District, Hangzhou 310016, China Tel: +86 571 2803 8088 John Wang is the senior partner of KPMG Hangzhou Office. He was previously a tax official in the Chongqing Municipality State Tax Bureau with more than seven years of tax audit and administration experience. John joined KPMG China after completing his MBA courses in the UK in 2004. In his career as a tax consultant at KPMG, John has deployed his good working relationship with tax authorities to help multinational and domestic clients in a wide variety of industries in dealing with their tax issues. He has also assisted many companies in the holding and financing structures of companies doing outbound investment or IPO in both domestic or overseas market. He is also a frequent speaker on seminars on the topic of Chinese tax matters and serve as advisers for a few high-profile research institutions. |

Grace Luo |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China 21 Floor, CTF Finance Center 6 Zhujiang East Road, Zhujiang New Town Guangzhou 510620, China Tel: +86 20 3813 8609 Grace Luo graduated from Sun-Yat Sen University in 2001 with a major in finance and taxation, and she joined the tax department of the KPMG Guangzhou office in the same year. She has been providing tax advisory and transfer pricing services for 16 years. Grace has been actively involved in providing tax efficiency planning, corporate restructuring, tax review and tax risk management advisory services to multinational and domestic clients. She has rich experience in assisting clients in communicating with tax authorities. In addition, she has abundant experience in various transfer pricing projects, including multinational and domestic transfer pricing audit and planning advisory. Grace is also a key member of KPMG's Centre of Excellence for indirect tax advisory services, which was established to cater to the Chinese VAT reform. So far, she has been involved in many domestic and multinational companies' VAT reform projects, including financial impact analysis, contract review, and advisory services on preparation and implementation for the VAT reform. Grace's clients cover a wide range of industries, including finance, automobiles, consumer market and retail, real estate, manufacturing and services, etc. Grace is a frequent speaker at public seminars held by KPMG. She is often invited as a speaker in seminars held by industry associations and educational institutions, as well as technical discussion interflows with China tax authorities. |