On February 11 2020, the OECD released its final guidance on financial transactions titled 'Transfer Pricing Guidance on Financial Transactions Inclusive Framework on BEPS: Action 4, 8-10', which will form Chapter X of the 2017 Guidelines. While the implications are broader than the financial services sector, this article highlights several aspects of the guidance that are relevant to financial institutions and includes emerging interpretation in key countries. There is a particular focus on implications for the banking sector given the combined complexities of regulation and funding.

Impact of regulatory constraints

The guidance requires accurate delineation of transactions as outlined in Chapter I of the OECD Transfer Pricing (TP) Guidelines. However, paragraph 10.15 of the guidance acknowledges that regulatory constraints play an important role in the determination of the terms of the contract of financial transactions.

The OECD specifically highlights the Basel requirements as an example of regulatory constraints that could affect the conduct of the parties and the terms of the financial transactions. The characterisation of loan assets or funding liabilities as 'short-term' and 'long-term', for example, could impact the calculation of a bank's net stable funding ratio (NSFR), a liquidity requirement introduced as part of the Basel III accord. A rolling inter-company deposit may be categorised and priced as a short-term asset, as it has to be readily available to the holder, notwithstanding that the deposit is maintained over a long period of time. Having regard to the "actual conduct of the parties", as set out in paragraph 10.22 of the guidance, needs to be balanced against the written terms of the contract and consequential regulatory impact.

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision have jointly required a global systemically important bank (G-SIB) to ensure that it has sufficient loss-absorbing and recapitalisation capacity available if it fails, in order to minimise the impact on financial stability, ensure the continuity of critical functions and avoid exposing public funds. This has resulted in G-SIBs needing to enter into financing arrangements that qualify as minimum requirements for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) and total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) debt (see the FSB's Principles on Loss-absorbing and Recapitalisation Capacity of G-SIBs in Resolution: TLAC Term Sheet, November 2015). A number of the characteristics of MREL or TLAC debt that govern the pricing analysis (such as tenor, subordination and the ability to be converted into equity) are based on these minimum requirements.

Paragraph 10.20 of the OECD guidance states: "In an ideal scenario, a comparability analysis would enable the identification of financial transactions between independent parties which match the tested transaction in all respects". However, it is important to note that many intra-group financial transactions within the banking sector, for example, do not have a precise analogue in the open market, precisely for the regulatory reasons highlighted above.

Benchmarking analyses for MREL or TLAC debt instruments, for example, may require adjustments or additional analysis for non-standard features, and may have limited comparable data, as they are generally not similar to financial instruments issued by non-banks. Accordingly, revenue authorities should be cautioned against the derecognition or re-characterisation of financial transactions in the financial services sector without acknowledging regulatory constraints and their impact on the terms and conditions of the financial transactions.

In the insurance sector, a point for consideration may be the delineation (in an intra-group situation) of funds withheld at Lloyds Bank, which can form part of the terms of a reinsurance contract, and the appropriate pricing.

Implicit support in the banking sector

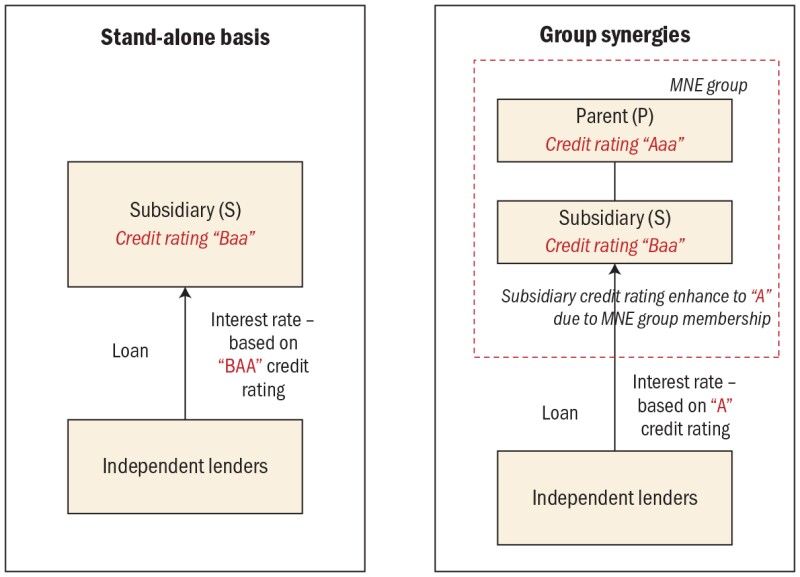

As part of a multinational group, subsidiaries may receive support from the group to meet its financial obligations in the event of financial difficulties, solely by virtue of group affiliation. This incidental benefit is referred to as implicit support.

A subsidiary in a non-financial services group typically has a credit rating that is lower than that of its parent, and implicit support may result in the subsidiary enjoying a higher credit standing than it would have based on its stand-alone characteristics.

The impact of implicit support is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Consistent with market practice, the OECD guidance in paragraphs 10.78 and 10.79 states that the likelihood of implicit support will depend on the links between the subsidiary and the rest of the group. This includes factors such as the identity of the subsidiary (e.g. shared name and brand), importance to the group's future strategy, operational integration and significance, reputational impact and history of group support.

The ultimate parent of a financial services group is generally required by the regulators inter alia to ensure that subsidiaries are sufficiently capitalised and have access to liquidity. This is to ensure they meet their obligations to creditors (refer to Articles 411 et. seq. of the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) in conjunction with Article 11 of the CRR, for example, as well as § 10 et. seq. of the German Banking Act and similar self-sufficiency rules). Rating agencies would very likely take into account these regulatory requirements for group support of subsidiaries.

However, the application of such guidance is not always straightforward for financial institutions. Following the 2008 financial crisis, most regulators require a framework for the recovery and resolution of financial institutions, including banks, in order to preserve financial stability and minimise the economic effect of future financial crises. The general rule of the group recovery and resolution plans are prepared for the group as a whole and identify measures in relation to the parent institution, as well as individual subsidiaries that are part of a group.

However, the recovery and resolution plans may specifically require a ring-fenced group or subsidiary to exclude certain entities or activities. Loans and off-balance sheet liabilities (such as guarantees) to entities outside the ring-fence may need to be properly accounted for regulatory reporting and capital calculation purposes. Therefore, this raises queries as to whether implicit support is assumed within a ring-fenced group, and prohibited outside of the ring-fenced group, notwithstanding factors such as a shared name and potential reputational impact.

Impact of recovery and resolution planning

Recovery and resolution planning also has an impact on funding flows within banks. The UK and the US have spearheaded recovery and resolution planning that adopts a 'top down' approach, resulting in a single-point-of-entry (SPE) for MREL funding (see the Bank of England's approach to MREL: Statement of Policy, June 2018). The SPE approach allows resolving the banking group at the level of its ultimate parent, rather than the operating company, in order to avoid disrupting the bank's balance sheet.

In a banking context, the adoption of an SPE approach results in several issues for both the parent and the operating banks. Some of these issues are further detailed below:

Within the banking sector, subsidiary banks typically have better credit ratings than the non-operating holding company as the banks are closer to the assets being created (i.e. loans written to customers). The same principle typically applies in the insurance sector and this is recognised by Moody's in its credit rating methodology for banks and insurers. For banking, a SPE structure would result in the replacement of external debt at the operating company level with inter-company funding from the ultimate parent. As a result, a bank subsidiary that has a better credit rating may have to borrow at a higher rate from its parent than what it could have borrowed from an independent lender.

Further to the point above, the bank subsidiary would need to remunerate its parent company for its role in 'passing on' the funding. The need to remunerate the parent company would result in additional funding costs to the subsidiary making inter-company funding more expensive than borrowing directly from third parties.

The gap in funding costs may be further exacerbated by 'maturity transformation', i.e. where the ultimate parent company is required to borrow long-term funds for capital purposes, but the subsidiary only requires shorter-term funding, having regard to the general tenor profile of its assets. Conversely, one would need to weigh up the realistic alternative for the borrower i.e. could it take on the same debt structure externally to achieve the same regulatory capital outcome overall and, therefore, factoring in any differences between the issuer and issuance ratings in the comparison.

Options realistically available: The lender and borrower perspectives

One of the key messages of the OECD guidance is that the TP analysis for financial transactions should reflect the options realistically available to the parties.

In that context paragraph 10.53 of the OECD guidance states: "The lender's perspective in the decision of whether to make a loan, how much to lend, and on what terms, will involve… other options realistically available to the lender for the use of the funds."

Likewise, paragraph 10.58 looks at the borrowers' perspective: "Borrowers seek to optimise their weighted average cost of capital and to have the right funding available to meet both short-term needs and long-term objectives. When considering the options realistically available to it, an independent business seeking funding operating in its own commercial interests will seek the most cost-effective solution, with regard to the business strategy it has adopted."

In the banking sector, the options realistically available to the borrower depend on the funding sources they can tap. While universal banks often have access to deposits, as well as secured wholesale funding and bonds issued in the capital markets, pure investment and wholesale banks are generally limited to the latter. From the borrower's perspective, the cost of the alternative funding options realistically available need to be taken in account when considering the arm's-length nature of the intra-group lending transaction as the borrower "will seek the most cost effective solution, with regard to the business strategy it has adopted".

The options realistically available to intra-group lenders in the banking sector for the use of the funds are generally the same as those of the intra-group borrowers: In principle, the lender could engage in corporate lending or trading transactions, if they had the required expertise, client base and infrastructure to do so. However, if these prerequisites were not already in place, these alternative options would not be realistic in the short-term.

Depending on the facts and circumstances, the comparable uncontrolled price method (CUP method) may be applied and arm's-length interest rates be based on the return of realistic alternative transactions for the borrower and the lender, e.g. bond issuances. In the evaluation of those alternatives as potential comparables it is important to bear in mind that, based on facts and circumstances, comparability adjustments may be required.

If no sufficiently comparable uncontrolled transactions are available to reliably apply the CUP method, the cost of funds approach may also be applied in accordance with the OECD guidance. The cost of funds approach may also be of relevance as a corroborative method to intra-group funding in the banking sector due to regulatory focus on the cost of liquidity.

In a nutshell, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank as well as other banking supervisors around the globe, have issued requirements and guidance to ensure that banks appropriately reflect the costs, benefits and risks of liquidity in their funds transfer pricing (FTP) frameworks. FTP is a strategic management tool that enables banks inter alia to establish a cost structure for internal funding based on the external funding profile of the bank. The FTP process allocates the funding cost to products and business lines that require funding based on their risk and maturity profile to allow for adequate product pricing and profitability measurement.

In that context, the source of funds and funding mix of the lender need to be considered. An intra-group lender that has access to customer deposits as a source of debt funding in addition to secured whole-sale funding and bonds issued in the capital markets, may have a lower cost of debt funding overall, even after taking to account the risk and cost of maturity and lot-size transformation. As the OECD guidance acknowledges that regulatory constraints need to be taken into account, the banking group's FTP framework therefore needs to be considered as part of any tax or TP analysis of intra-group lending transactions.

Remuneration of the treasury function

The OECD guidance recognises that the organisation of the treasury function will depend on the structure of the group and the complexity of its operations and may be subject to specific regulatory requirements, e.g. in the banking business. Accordingly, the approach of the treasury function to risk will depend on the group's policy to implement these requirements, e.g. liquidity coverage ratios or the NSFR described above. In that context, the key function of the treasury department generally is to make the process of funding the group's operating businesses as efficient as possible following the vision, strategy and policies set out by group management. The treasury function usually entails raising external borrowing, such as bonds and other forms of debt, and making it available to the borrowers in the group.

In a universal banking group, the treasury function might also entail centralising funding raised by the lenders in the group that have access to deposits as described above and passing it on. Where treasury performs such agency or intermediary functions, they are typically to be regarded as a support service to the main value-creating operating businesses of the group. Therefore, it may be appropriate to determine the arm's-length pricing as a risk-free rate of return on the funds 'passed-on' or a mark-up on the costs of the treasury function itself in line with the guidance in Chapter VII of the OECD Guidelines.

The OECD recognises, however, that the treasury may also be found to perform more complex functions and should be compensated accordingly in that case. As with a lot of the OECD guidance, it is primarily written with non-financial services multinationals in mind, and how the treasury and hedging commentary is interpreted in a banking context where the complexity and volumes take on a completely different scale will be a point for debate.

Emerging interpretations

The US has so far only indicated that it might take the OECD guidance into account as a reference point should it decide to issue TP regulations on financial transactions. The UK, however, has compliance with the OECD TP Guidelines enshrined within domestic law. That said, there may be an inherent conflict between that provision and the requirement in the UK TP legislation to ignore guarantees (implicit or explicit) when pricing financial transactions. As such, some further guidance from Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs (HMRC) on this point can be expected as the OECD guidance on financial transactions is final.

Meanwhile, Germany has recently issued draft legislation focused on in-bound lending that reflects the rebuttable presumption that the interest rate charged to the German borrower should not exceed the group's cost of external debt funding unless the taxpayer can demonstrate that a higher rate would be more appropriate. Likewise, the treasury function is generally assumed to be a routine support function to be remunerated with a cost-based approach.

Given the absence of thin capitalisation rules in Luxembourg, as another example, the OECD guidance is expected to become the reference framework in Luxembourg for the determination of appropriate debt-to-equity ratios, replacing the historical 85:15 ratio typically applied by Luxembourg entities in practice. This is a significant development for the asset management industry, in particular, in the real estate and private equity sectors, as the changes will impact fund vehicles and corporate taxpayers in Luxembourg.

For these alternative sectors, the introduction of interest restriction rules (following BEPS Action 4) in domestic legislation across the globe can impact shareholder debt from a tax perspective in any event, regardless of TP or thin capitalisation provisions, although potentially less so in a sector like banking with a net interest income profile.

Many countries are yet to formally incorporate the OECD's latest guidance on financial transactions into local laws and regulations, and those that do may not adopt the guidance in its entirety. It may also be tested as loan documentation is amended on the London interbank offer rate (LIBOR) transition.

At the same time, financial institutions around the globe are grappling with the implications of the COVID-19 crisis, including increased risks of a liquidity crunch across all sectors and further pressure on bank's interest margins due to central banks aggressively cutting interest rates. FTP models may require significant adjustments to reflect liquidity stress testing results with corresponding knock-on effects on the pricing of financial transactions between legal entities and branches of the group. As such, it would be particularly important to carefully monitor developments in this area against the backdrop of the COVID-19 crisis.

Click here to read the entire 2020 Deloitte/ITR Financial Services Guide

Stephen Weston |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Deloitte UK T: +44 20 7007 4568 Stephen Weston is a partner in Deloitte UK's financial services tax group, and leads the financial services TP team. Over a career spanning 30 years, he has advised a number of multinational corporate and financial institutions on the taxation of international finance and treasury and TP matters. He also has tax audit, direct tax litigation and advance pricing agreements (APA) experience in these areas. Stephen's financial services sector clients include global banks and insurance groups. He is the Deloitte global lead for banking TP. He also leads the firm's approach to significant people functions (SPFs) in the context of the UK controlled foreign company (CFC) state aid case. Stephen is a qualified chartered accountant and a full member of the Association of Corporate Treasurers. |

Silke Imig |

|

|---|---|

|

Director Deloitte Germany T: +49 69 75695 7266 Silke Imig is a director working with Deloitte in Frankfurt. She specialises in financial services TP and has more than 19 years of experience in this area including on the provision of TP and related tax advice for corporate banking, asset and wealth management, research, IT and the treasury. Recent projects have included advising clients in relation to tax audit challenges, APA and mutual agreement procedures (MAPs) as well as reorganisations due to the Brexit, MiFID II, FTP changes and other restructuring. Silke is an Institute of Chartered Accounts for England and Wales (ICAEW) qualified chartered accountant and has worked in London, Washington and New York, before returning to Germany. Prior to joining Deloitte, Silke was responsible for developing, operationalising and defending TP arrangements for a number of businesses globally for a universal banking group in Frankfurt for more than 10 years. |

Priscilla Ratilal |

|

|---|---|

|

Director Deloitte UK T: +44 20 7007 8164 priscillaratilal@deloitte.co.uk Priscilla Ratilal is a director in the Deloitte UK financial services TP team. She has more than 14 years of experience and has worked in Sydney and New York, before moving to London. Priscilla has advised a number of clients in the financial services sector including asset management, banking and insurance. Her client experience includes TP policy development, preparation of documentation, operational TP issues, country-by-country reporting (CbCR) and engaging with tax authorities, in the context of both APAs and audits. She also has experience in pricing intra-group loans and guarantees, and determining an arm's-length reward for treasury activities. When based in New York, Priscilla had in-house experience in a diversified financial services group, managing TP for the Americas region for a range of business units including commodities and financial markets, agency stockbroking for cash equities, fixed income and equity derivative trading, investment banking, aviation leasing and asset management. |