The manner in which dividend income is taxed in India has undergone several changes over the years. In 1997, India introduced the dividend distribution tax (DDT) regime wherein dividend income was exempt in the hands of the shareholders, but the company paying the dividend was required to pay DDT at a flat rate, irrespective of the tax rate applicable to respective shareholders. However, in 2002, the incidence of dividend tax was shifted to the shareholders, and then shifted back into the hands of the company during 2003.

India has since re-introduced the classical system of taxing dividends in the hands of the shareholders as was prevalent in the past. The classical system of taxing dividends will be effective from financial year (FY) 2020-21 and will apply to dividends distributed on or after April 1 2020. While the former DDT regime had the advantage of ease of tax collection, it significantly increased the cost of doing business in India.

This was apparent, especially for foreign investors, as there were issues on availing credit of DDTs in their home jurisdiction (given that DDT was a tax on the company and not on the shareholders) and thereby leading to double taxation in many cases. The effective DDT rate of 20.56% was also significantly higher than the maximum rate at which India would have had the right to collect tax under most of the relevant tax treaties. Given the re-introduction of the classical system of taxing dividends coupled with reduced corporate tax regimes introduced in 2019, India has emerged as an attractive destination for foreign investors.

The dividend tax regime's impact on non-resident shareholders

If dividends are paid to non-resident shareholders, tax is required to be withheld at 20%, plus applicable surcharge and cess, subject to tax treaty benefits where a lower rate can be availed. The lower withholding tax (WHT) rate can be availed subject to satisfaction of several conditions as discussed below.

There are several countries where the tax treaties prescribe a much lower rate than the domestic rate of 20%. For instance, India's tax treaties with Mauritius, Hong Kong SAR, Singapore, the UK, Switzerland, etc. prescribe a WHT rate in the range of 5% and 10%.

Further, recourse can also be made to the most-favoured-nation (MFN) clause, which is present in several of India's tax treaties, which permits the originally negotiated WHT rate to be further reduced subject to the satisfaction of certain conditions. However, taxpayers would need to answer several questions (listed below) in order to take advantage of the MFN clause and consequential lower WHT rate:

Whether the protocol containing the MFN clause applies automatically or requires a separate notification from the competent authorities of India?

The tax treaties (for example, Colombia and Slovenia) having a 5% WHT rate for dividends have been negotiated by India when such countries were not members of the OECD. Given the language of the MFN clause, an issue could arise on whether the benefits offered through the MFN clause can be taken in cases where such countries are not OECD member countries at the time of signing a tax treaty but become an OECD member at a later point of time.

We have summarised the WHT rates on dividend income (including benefit of the MFN clause) of several of India's key tax treaty partners in Table 1.

Instead of Colombia, the benefit of the India-Slovenia tax treaty can also be taken, which provides for a 5% WHT rate on dividends provided the recipient of the dividend holds at least 10% of the capital of the company paying the dividends; otherwise, the WHT rate would be 15%.

However, under the Multilateral Instrument (MLI), the India-Slovenia tax treaty also prescribes a minimum holding period of 365 days to avail the 5% WHT rate. Taxpayers who intend to rely on the MFN clause to take advantage of the 5% WHT in the India-Slovenia tax treaty may also need to comply with the 365 days holding period along with the minimum 10% shareholding criteria.

Further, credit for taxes withheld in India will be available in the overseas jurisdiction in accordance with their applicable tax credit rules. However, the WHT may become a tax cost if the dividend income is exempt and hence not taxable in the country of residence of the non-resident shareholders.

Table 1 |

|||||

Serial Number |

Treaty |

WHT rate on dividends |

MFN clause present |

Country whose WHT rate is sought to be imported |

Applicable WHT rate pursuant to MFN benefit |

1 |

India-France |

10% |

Yes |

Colombia |

5% |

2 |

India-Germany |

10% |

No |

NA |

NA |

3 |

India-Hong Kong SAR |

5% |

No |

NA |

NA |

4 |

India-Hungary |

10% |

Yes |

Colombia |

5% |

5 |

India-Malaysia |

5% |

No |

NA |

NA |

6 |

India-Mauritius |

5% |

No |

NA |

NA |

7 |

India-Netherlands |

10% |

Yes |

Colombia |

5% |

8 |

India-Sweden |

10% |

Yes |

Colombia |

5% |

9 |

India-Singapore |

10% |

No |

NA |

NA |

10 |

India-Switzerland |

10% |

Yes |

Colombia |

5% |

11 |

India-US |

15% |

No |

NA |

NA |

12 |

India-UK |

10% |

No |

NA |

NA |

Availability of tax treaty benefits

The availability of tax treaty benefits to non-resident shareholders is subject to the satisfaction of several anti-abuse provisions. For instance, the recipient must be a 'beneficial owner' of the dividends in order to be eligible for a lower WHT rate. In addition, the principal purpose test (PPT) pursuant to the MLI, wherever applicable, would need to be satisfied. Lastly, it must also be ensured that the transaction is not hit by the provisions of the domestic general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR). The previously mentioned concepts are discussed in brief below.

Beneficial ownership test

A lower WHT rate provided in a tax treaty is available only to a person who is the 'beneficial owner' of the dividend income. There have been several judicial precedents which have held that the recipient of an income may not qualify as a beneficial owner if its right to use and enjoy the income is constrained by a contractual and legal obligation to pass on that income to its shareholder or any other person.

In the context of the India-Mauritius tax treaty, the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) has issued Circular No. 789, dated April 13 2000, which states that a tax residency certificate (TRC) will constitute sufficient evidence for accepting the status of residence as the beneficial ownership. The Supreme Court in the case of Azadi Bachao Andolan has upheld the validity of the aforesaid circular.

However, given the changed tax landscape, it is imperative to undertake a detailed factual analysis, identify risk factors and implement solutions rather than merely relying on the TRC for satisfaction of the beneficial ownership test.

It is pertinent to note that, recently, the Authority for Advance Rulings (AAR) in the case of Tiger Global International Holdings denied the benefit of the India-Mauritius tax treaty, inter alia, on the grounds that the control and management of the assessee was located outside Mauritius and that it was not the beneficial owner of the underlying assets. The AAR ruled that the structure was designed prima facie for the avoidance of tax and hence not eligible for tax treaty benefits.

Another issue which arises for consideration is that assuming the immediate recipient of dividend income is not eligible for tax treaty benefits on the basis that s/he is not the beneficial owner, then will the dividends be taxed as per the domestic tax law or can recourse be made to the treaty WHT rate of the ultimate beneficial owner? This position is untested in Indian jurisprudence and one should proceed with caution before adopting this approach.

Principal purpose test

Prevention of tax treaty abuse is undoubtedly one of the most significant areas dealt with as part of the OECD's BEPS project. Several of the measures that were announced as part of the BEPS project are dealt with by way of changes to the tax treaties. Towards this, the MLI provides for an alternative mechanism for modifying bilateral tax treaties and thus avoiding a need for simultaneous negotiation of thousands of tax treaties.

An important outcome of the BEPS project, read with the MLI, is the enactment of the PPT. As per the PPT, the treaty benefits can be denied if obtaining such a benefit was one of the principal purposes of an arrangement or transaction unless such a benefit is in accordance with the object and purpose of the treaty. The satisfaction of the PPT is perhaps one of the most challenging exercise because of the inherent subjectivity coupled with the broad language of the provision.

In order to deny the treaty benefits, the tax authorities only need to substantiate that it is 'reasonable to conclude' that 'one of the principal purposes' of any arrangement or transaction was to obtain a treaty benefit. As such, the tax authorities are left with much discretion in interpreting the requirements of the PPT. Given that the PPT is a recent anti-abuse provision, the scope and impact of the same remains untested thus far by the judiciary.

Minimum holding period

In addition to satisfying the test of beneficial ownership and the PPT, the MLI also provides for a minimum shareholding period of 365 days, in order to avail the beneficial tax rates provided under the tax treaties.

As of July 2020, this provision of the MLI is applicable only for India's tax treaties with Canada, Denmark, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia.

General anti-avoidance rule

The provisions of GAAR (as applicable from April 1 2017) give wide powers to the tax authorities to deny tax benefits (including tax treaty benefits) arising from an 'impermissible avoidance arrangement' if, inter alia, the main purpose of the arrangement is to obtain a tax benefit.

Given the above, it becomes imperative to carefully analyse the provisions of tax treaties, wordings of MFN clauses, changes due to the MLI, etc. to determine the treaty eligibility and the appropriate WHT rate.

Cascading effect of dividend taxation in cases of multi-tier holding structures

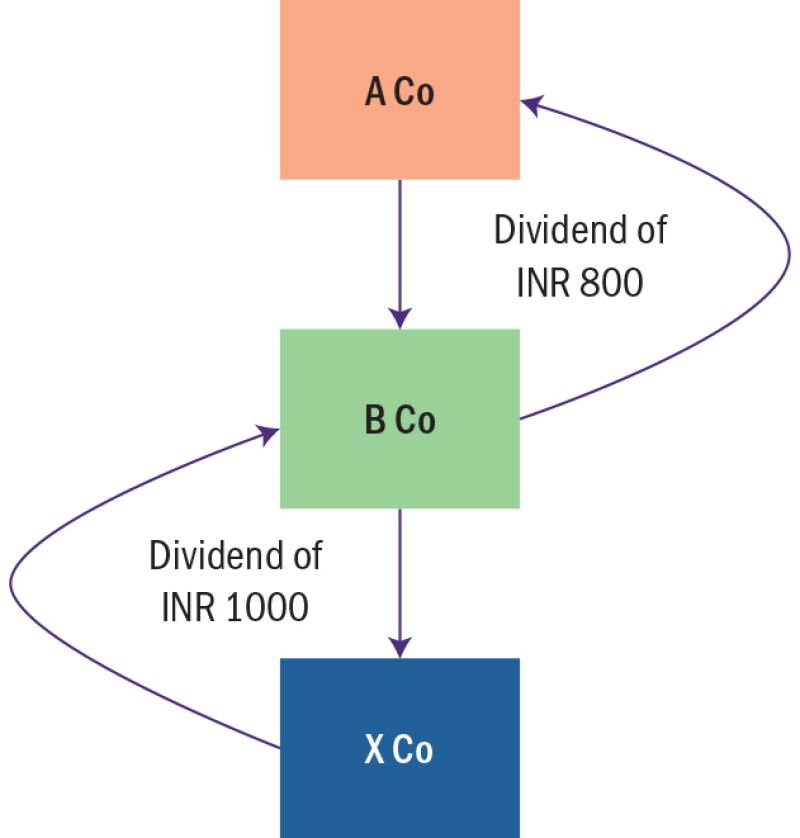

Furthermore, in order to remove the cascading effect of taxation in a multi-tier holding structure, a rollover benefit for dividend income is permitted. This is pictorially explained in Figure 1.

Figure 1

In the example, X Co (which could be a domestic company or a foreign company) distributes INR 1,000 ($13) as dividend to B Co, which in turn distributes INR 800 as a dividend to A Co.

In order to prevent the cascading effect of taxation of the same dividend income, the law permits a deduction of INR 800 in the computation of income of B Co, provided that B Co has upstreamed the dividend income to A Co at least one month before the due date of filing its tax return of the year in which the dividend was received.

In such a case, B Co will be taxed only on the net dividend income of INR 200. It may be noted that such deduction is allowed irrespective of the percentage of shareholding in X Co and regardless of whether X Co is a domestic company or a foreign company.

Deduction for expenses incurred for earning dividend income

Given that the dividend income is taxable in the hands of the shareholders, the controversy surrounding several issues on disallowability of expenditure incurred to earn dividend income, which was earlier exempt, no longer survives.

However, the law provides that no deduction other than interest expenditure shall be allowed as a deduction from dividend income. Further, the deduction on account of interest expenditure shall be restricted to 20% of dividend income which is included in the total income of a resident shareholder. It may be noted that no such interest deduction is allowable to non-resident shareholders. Dividends received from a specified foreign company is taxable at 15%. However, in computing such dividend income no deduction for any expenditure, including interest expenditure, or allowance is permitted.

Outbound investments from India

While the previously mentioned discussion was largely in the context of inbound investments into India, the tax and regulatory laws in India also do provide a favourable regime with respect to outbound investments from India. For instance, while India does not provide for a participation exemption, dividend income earned by an Indian company from a foreign subsidiary is taxable at a concessional rate of 15%. Further, the rollover benefit to prevent the cascading effect of taxation is also available to foreign dividend income.

Structuring outbound investments (either directly or through an intermediate holding entity), choice of funding (debt or equity), choice of entity (subsidiary or partnership), satisfaction of several anti-abuse provisions, etc. are some of the important parameters that one needs to be mindful about in order to ensure overall tax efficiencies in the structure.

Concluding remarks

The abolition of the DDT regime and the re-introduction of the classical system marks a paradigm shift in the taxation of dividends in India. WHT, which used to be a sunk cost for non-residents, will henceforth be creditable in their home country due to the shift in incidence of tax from the company to the shareholder.

Further, the benefits granted by several tax treaties in terms of a lower WHT rate would assume significant importance and can go a long way in reducing the cost of doing business in India. Of course, the aspects pertaining to treaty eligibility, satisfaction of the PPT and beneficial ownership test, and applicability of GAAR, would need to be thoroughly examined.

Foreign investors would, therefore, need to critically assess the impact of this new dividend tax regime on their holding structures and take appropriate actions to achieve optimal tax efficiencies.

Mehul Bheda |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Dhruva Advisors T: +91 22 6108 1005 mehul.bheda@dhruvaadvisors.com Mehul Bheda is a partner at Dhruva Advisors. He has more than 15 years of experience in the field of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) tax and advisory. Mehul has advised Indian and multinational clients on restructurings, mergers and other arrangements. He has been actively involved in tax due diligence and international/cross-border tax structuring for private equity and strategic M&A transactions. He has also been involved in the reorganisation of promoter family interests and family settlement arrangements. Prior to joining Dhruva Advisors, Mehul had started his career with Arthur Andersen. He later worked in the transaction tax teams at PwC and EY. He is a member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI). |

Saurabh Shah |

|

|---|---|

|

Principal Dhruva Advisors T: +91 22 6108 1034 saurabh.shah@dhruvaadvisors.com Saurabh Shah is a principal at Dhruva Advisors. He has more than 13 years of experience in the field of domestic and international taxation. Saurabh has advised Indian and multinational clients on indirect transfers, structuring of inbound and outbound investments, India entry strategies, cash repatriation, managing effective tax rate, and treaty analysis, among other areas. He has vast experience in representing clients before the tax authorities and courts in India. He is also actively involved in tax advocacy matters and supports various industry associations on tax policy issues. Saurabh is a part of the core knowledge and solutions team at Dhruva Advisors. Prior to joining the firm, he was associated with EY for more than seven years. He is a member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI). |