To ensure there is a consistent application of the arm’s-length principle (ALP), transactions happening between unrelated parties and related parties should be aligned with profit allocation and the international business environment.

This alignment has several advantages, such as creating simpler multilateral tax conventions, having a standardised application of these treaties to specific cases and increasing the chances for single states to agree on a specific multilateral tax treaty because it becomes a matter that goes beyond unilateral interests.

Drafting a simplified multilateral tax treaty model

It is important to consider how a multilateral tax treaty could be simplified with a few initial observations.

Firstly, as a general principle, the fiscal presence of an individual in a country during most part of the year can be regarded as a valid criterion for establishing a taxable presence. This can, therefore, become the simplest criterion to determine the tax residence of an individual and which jurisdiction is entitled to tax that individual’s income.

Looking more at the economic reality of businesses, a company is present and managed in a country from which its main decisions are taken and where its main functions, assets and risks (FARs) are located. Based on this, a valid criterion for the recognition of taxation could eventually be the place from where the entity is effectively managed. It simply makes sense that an entity pays corporate income taxes in the country of its formal and substantial economic presence.

With the ALP, the pricing of transactions based on the market conditions is extended to the ones between related parties. Further, a company that has a certain level of activity and FARs granting the possibility to operate should receive a profitability based on margins recognised in the open market for similar circumstances. Economically speaking, the market should be the driving factor to price all economic transactions, both related and unrelated, and to attribute margins to all entities.

In regards to permanent establishments (PEs), if a company has a business in another country, it makes also sense from an economic and tax perspective to consider such a business as autonomous as if it was under an independent company. The attribution of the income to the PE then becomes a pure transfer pricing (TP) matter as far as deemed related-party transactions are attributable to such a PE.

Following the considerations above it would be possible to conceive a simplified multilateral tax convention based on two fundamental principles:

Incomes are taxable in the state of tax residence of an individual or company; and

TP rules would apply where a taxpayer has a fixed place of business used to carry on an unincorporated business in another state that is part of the multilateral tax treaty and that income economically relates to such other business.

Simplified multilateral tax treaty

The main provisions of a tax treaty could be simplified with just a few changes. Although there is a risk of over-simplification, the purpose is to provide a practical outcome of the conceptual framework.

Below are examples of treaty articles in their simplified form, with some clarifications related to interpretation and application. For the sake of completeness, the clauses are partially based on the Income and Capital Model Convention and Commentary (Condensed Version) OECD (2017).

Article 1: Definitions

Individuals and companies can be considered equivalent from a tax perspective and therefore also in terms of tax residence. For example:

“For the purposes of this convention, unless the context otherwise requires, the term “person” includes an individual, a company and any other body of persons.”

In relation to permanent establishments, these can be defined through a theoretical approach or by means of examples but at the end it should always imply the fact that there is an economic physical presence in a certain state, allowing the economic attribution of income based on transfer pricing guiding principles. For example, the treaty text could state:

“For the purpose of this convention, permanent establishment means a fixed place of business needed to carry on an economic activity.”

Article 2: Applicability of the convention

This proposed Article 2 intends to offer a systemic approach to a multilateral tax treaty, by stating: “This convention shall apply to persons who are domestic tax residents of one or more of the contracting states.”

As such, this text would refer only to a concept of tax residence based on domestic tax law as a requirement for the applicability of the multilateral tax treaty and not to one that is needed – as explained below – for applying in concrete the distributive rules of the convention.

Article 3: Tax residency for the purpose of the convention

A person is not supposed to be tax resident in more than one country participating to the multilateral tax treaty at the same time because this would result in the main allocating criterion losing its effect. As such, Article 3 could be simplified to state:

“For the purposes of this Convention, a person can only be a tax resident in one country based on the following criteria:

For an individual based on the location where he/she spends most of the time during the year; and

For a corporation, based on the location of the effective management.”

Such an approach justifies the presence of:

Tie-breaker rules to establish where the person is tax resident, which cannot be in more than one tax treaty state; and

The existence of the possibility to have a procedure to reach an agreement to solve the problem of the tax treaty residence and make the tax treaty effective.

Article 4: Allocation of income

Article 4 could be simplified to the following:

“Incomes shall be taxable only in the state in which a person is resident for the purpose of the tax convention.

If a person carries on a business, the profits that are attributable to the permanent establishment based on acceptable transfer pricing mythologies shall be taxable only in that other state.”

In the clause, there is a reference to the concept of a person to extend, due to the preliminary definition, the application of the tax treaty criteria to companies and individuals at the same time.

The idea of the reported clause in a multilateral treaty context is to give exclusive taxing rights to the country at source in relation to the income that is attributable to the business presence. Obviously, the same result can be reached if the resident state is entitled to tax and gives a full exemption in relation to the income connected with the source state. A tax credit would reach a different outcome as the effective tax burden will be based on the corporate income tax rate of the resident state.

However, the source criterion should be defined in a strict manner as the place in a jurisdiction where there is a fixed place of business to carry on an economic activity or simply a PE. Other criteria for the attribution of a source taxation are not justifiable from an economic standpoint, such as the pure payment of an amount (exclusion of withholding taxes (WHTs) for cross-border transactions) because it does not refer to the existence of an economic activity defined in terms of FARs.

After having reduced the PE as the sole criterion to trigger source taxation and having given meaning to PEs in terms of economic presence that justifies the potential attribution of profits and margins for tax purposes or for the allocation of taxing rights, the matter becomes purely a question of the application of the ALP with the consequent need to proceed with a FAR analysis.

Article 5: Dividends

Dividends simply represent the income that was already taxable, and eventually taxed, at the level of the recognising entity. As such, Article 5 could state:

“Dividends received by an individual tax resident in a state that is a participant to the convention shall not be taxable in such state.”

With the implementation of the clause above, it is possible to eliminate one case of economic double taxation that might arise when the dividends are taxed twice through corporate income taxation at the level of the distributing entity and at the level of the receiving entity. Because of the combination of Article 5 with the Article 4 mentioned above the dividends are fully excluded from taxation from both resident and source perspectives unless the dividend can be connected to a fixed place of business in the jurisdiction, which is a participant of the multilateral tax treaty, of the distributing entity.

The four main characteristics of the tax convention above can be listed as follows:

Drafting of treaties based on two fundamental principles: residence and source;

Identification of source with a fixed place of business, i.e. PE;

Attribution of exclusive taxing rights to the source state; and

Elimination of economic double taxation in relation to the distribution of dividends.

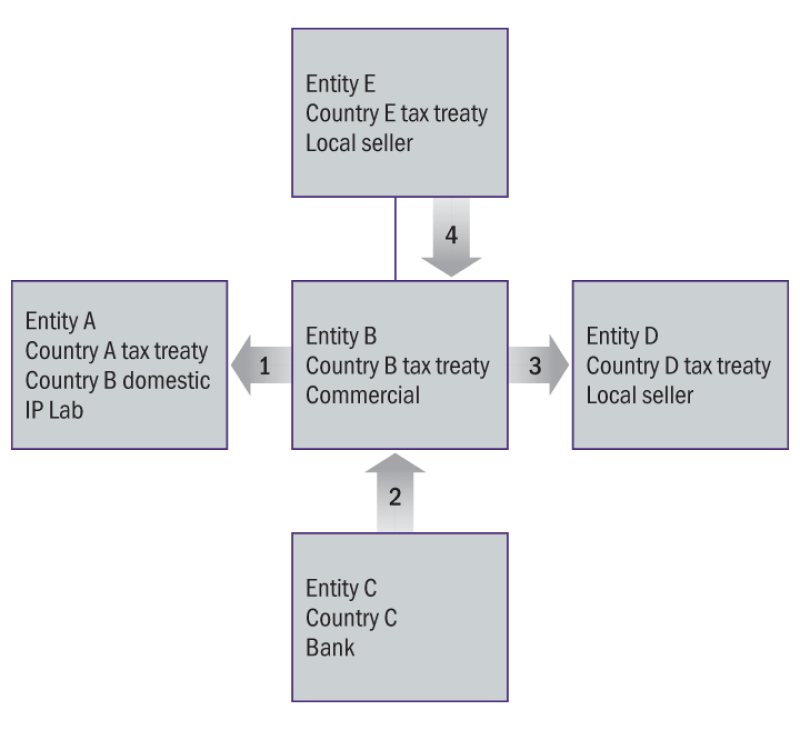

Example of the four main characteristics of the proposed simplified tax convention

The above example assumes there is a multilateral tax treaty between countries A, B, C, D and E. Entity A is a domestic tax resident of Country B. This triggers the applicability of the multilateral tax treaty based on Article 2. Under Article 3, Entity A is tax resident in Country A because that is where its effective management is.

Entity A, located in Country A, performs R&D activities and is charging a royalty for the use of intangible assets that have been developed. Domestic tax law of Country B normally applies a WHT equal to 10% on the cross-border payments of royalties. Due to the application of the multilateral tax treaty, and in particular under Article 4, Entity B should not apply the mentioned WHT as such income is only taxable in country A, taking into consideration that Entity A does not have a PE in Country B.

Entity C, located in Country C, is a bank that lends money to Entity B that was used to develop a global commercial platform. Entity B pays an interest to Entity C. Domestic tax law of Country B normally requires the application of a WHT of 15% on cross-border payments of interests but Article 4 of the multilateral tax treaty states that this income is only taxable in Country C. The multilateral tax treaty means there is no possibility for Country B to apply the WHT on the interest, also because Entity C does not have a PE in Country B.

In the graphic above, Entity B is distributing a dividend to Entity E based in Country E. Country E does not exclude dividends from taxation and applies a corporate income tax rate of 20%. However, it cannot apply this tax rate due to the presence of Article 5 of the multilateral tax treaty that excludes the taxation of dividends at the level of the resident state. In addition, domestic tax law of Country B normally has a WHT of 15% on dividend, but Country B is restricted from taxing due to the presence of Article 4 because the dividend payment is not connected with the presence of a PE.

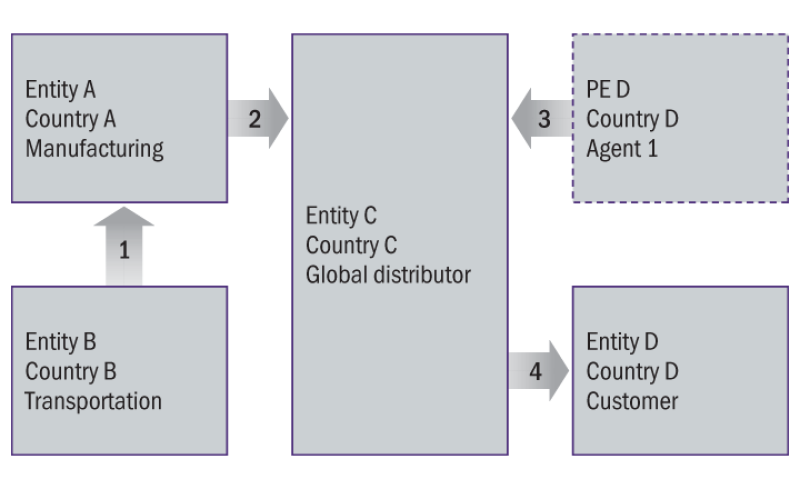

Example of the application of the proposed multilateral treaty across four entities

The below example shows that all the entities are entitled to the multilateral tax treaty that has been signed between countries A, B, C and D. This is because these entities are considered tax residents from a domestic perspective in one of the signing countries.

As per Article 3, Entity B is tax resident from a tax treaty perspective in Country B and receives transportation service fee from Entity A, a resident in Country A. It is not relevant that, from a domestic tax perspective, Entity B is a tax resident in another treaty country. Under the multilateral tax treaty, the transportation fee is taxable only in Country B as per Article 4 because there is no PE presence of Entity B in Country A.

Entity A is manufacturing goods and selling them to Entity C, which is a tax resident under Article 3 of the multilateral tax treaty in Country C. The income derived from the transaction is taxable only in Country A under Article 4 of the multilateral tax treaty.

Entity C is receiving an income from Entity D in relation to the sale of goods that is only taxable in Country C, unless there is a PE of Entity C in Country D and some of the income can legitimately be attributed to this PE. As there is a PE of Entity C in Country D (having an agent function) and some income can be attributed to the agency PE, then some of the income recognised in Country C should be excluded from taxation in this country as the income attributable to the agency PE under the multilateral tax treaty is only taxable in Country D.

Multinational taxpayers

The approach proposed above has significant advantages for multinational taxpayers as the allocation of the profit generated would be treated under the umbrella of the same system, assuming that all the jurisdictions in which the multinational company operates are covered by the multilateral tax treaty as in the examples above. In addition, all the matters related to the taxation at source would be automatically converted into a pure TP allocation.

Further, the reduction of WHTs applicable under the multilateral tax treaty – only acceptable theoretically if there is a PE connection – would avoid two main negative scenarios:

The WHT paid at the level of the source state is not recoverable and there is no exemption available at the residence state level in relation to interests, royalties and dividends. In such a case, the exclusion of the WHT would eliminate cases of juridical and economic double taxation for the multinational taxpayer.

The WHT represents simply a credit for the taxes to be paid in the residence state. In such a case, the total direct tax burden of the taxpayer is computed on the total income based on the tax rate of the residence state. Economically, this situation represents a distortion as taxpayers should be taxed economically in the place where the income is generated based on the appropriate allocation of FARs. Also, in such a case, the exclusion of the WHT would solve the matter.

Further, the reduction of the WHTs under the proposed model has a positive effect by decreasing compliance related to the payment of such taxes, e.g. declaration, payment, tracking in the internal accounting systems. It is also linked to the right to obtain an exemption or a tax credit at the residence state of the relevant entity, e.g. submission of certificate of residence, evidence of the WHT payment.

The simplified approach recommended above should not only be a theoretical exercise to close the gaps between current tax treaty clauses and economic reality but should have the potential for practical implementation, even if some adjustments at domestic level might be required. For instance, a domestic jurisdiction willing to join a multilateral tax treaty might need to increase some domestic taxes to compensate the loss derived from the restrictions on the WHTs.

The final proposal for a draft multilateral tax convention based on the principles mentioned above – not to be modified in its essence by the position of the single participating countries – should come from international organisations like the OECD or the UN. Multinational enterprises can only bring the matter to the attention of the international community as an effort to reach higher global tax standardisation.