This era of digitisation (or ‘digital transformation’) is synonymous with developing and implementing digital capabilities into all aspects of any business; converting processes that enable companies to capture, control, analyse, and utilise the flow of information in a comprehensive manner using digital tools. While several companies were already making strides towards a greater digital footprint, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need to create agile supply networks through greater adoption of technology and data-driven-decision making (DDD).

This article explores how digital transformation in companies gives rise to new sources of value and how such value creation can be appropriately identified and addressed within a TP analysis. It is important to note that our focus is on internal transformations of supply chains and therefore does not relate to the ongoing pillar one and pillar two discussions being led by the OECD.

In the world post-COVID-19, many multinational enterprises (MNEs) are seeking digitally enabled initiatives to drive technology and process changes. To achieve the benefits and scale of digital technologies, data has become a source of significant value. However, the data must be tuned for native machine consumption, causing organisations to rethink processes around data management, capture, and organisation.

This can, in turn, allow organisations to augment their decision-making process by using data to drive smart, real-time decisions to enhance productivity. By using data consolidation and analytics, basic workforce decision-making and crew management can be automated or semi-automated, freeing up capacity to focus on exception management and longer-term strategic deployment and allocation of human capital. This trend has been heightened post pandemic where companies have started making significant investments in digital technology for sustaining their competitive advantages.

The GOAL framework

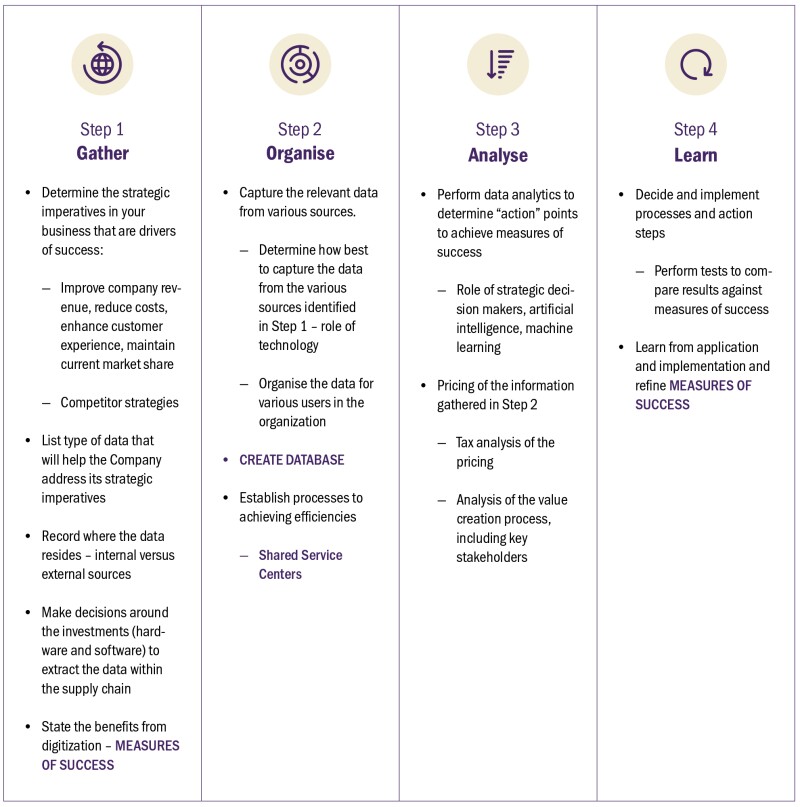

One key attribute of almost all the digital transformation projects is that the new infrastructure builds the foundation for present and future digital business applications and processes. Assuming a company undergoes the digital transformation and creates a huge database of reliable and standardised data, the process of gathering the data, organising the data in a standardised database and analysing it to get some meaningful actionable insights form important steps in value creation in a digital supply chain. This is what we refer to as the GOAL framework – a structured approach to recognise how value is created from Gathering, Organising, Analysing and Learning from the data in a digitally enabled supply network. Each of these steps in the GOAL framework may be a significant source of value and the value is ascribed to the key people that control the important decisions in each step.

The Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, and Protection (DEMP) framework in the 2017 OECD Guidelines can be applied to this four-step GOAL framework. For example, imagine a company that embarks on a digital strategy to develop a ‘smart factory’.

A smart factory is a highly digitised shop floor that continuously collects and shares data through connected machines, devices, and production systems. The data can then be used by self-optimising devices or across the organisation to proactively address issues, improve manufacturing processes and respond to new demands.

In setting up the smart factory, the company will need to decide on what data it needs to track and gather (and the process for capturing this data), where the data can be centralised and maintained in an organised manner, the analytics that need to be performed on the data to enable DDD, and the learning process that will enable a constant process improvement to instill greater efficiency in the decision-making process.

Each of these steps require investments in software and hardware, important decisions as well as maintaining and protecting the data within the company. This, in essence, boils down to identifying the DEMP functions of this source of value. The profits should therefore be aligned with the location of the important decisionmakers.

The GOAL framework is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Assessing value creation in digitalisation initiatives: GOAL framework

The operational elements discussed in the GOAL framework allow its application in any industry. Before diving into the first step, establishing a cross-functional ‘project management team’ is of vital importance. This team usually comprises of experts in the fields of technology, management, legal, corporate finance (including tax) as well as external consultants and is responsible for administering and managing cross-functional firm-wide projects from inception to completion.

The first step ‘Gather’ sets the stage for the project management team to determine the strategic imperatives of the business and how it fits within the industry in which the company operates.

During the initial phase of the project, it is essential for the project management team to realise that such initiatives not only have business considerations but also have tax consequences that need to be factored in while making such investment decisions.

Some of the key steps in this stage include conducting initial research and carrying out scenario analyses on how the company’s productivity or market share will change based on the proposed digital transformation initiatives, reaching out to the appropriate subject matter experts as needed, planning on how data at various nodes within their supply chain can be recorded and extracted, and presenting the project to the senior management to obtain requisite approvals. The goal of this exercise should be to create a blueprint of how the digital transformation investment will address the strategic business imperatives and benefit the company.

Once the initiative is approved, the project management team proceeds with the next step of the GOAL framework – ‘Organise’. The goal of this step is to create a repository of standardised data i.e., organising myriads of data into actionable formats, which is easy to understand by various stakeholders within the supply chain. This requires building an algorithm to search, filter, sort, and combine various sources of data in an efficient manner. In other words, this step involves development of a database – a valuable intangible asset.

As a part of this step, companies often set up a shared service centre (SSC), a separate legal entity within the group to separate the functions, risks and assets associated with the implementation of digital transformation related decision. This database also needs to be continuously enhanced and protected and the decision-making process surrounding such steps can also be drivers of economic value.

The standardised data hosted by the SSC can be utilised for gaining actionable insights either by themselves or other entities (here, the internal ‘customers’ of the data). The data analysts within the SSC or any other group entity can use the standardised data to perform scenario analysis under the direction of the experts within the organisation.

This constitutes the next step of the GOAL framework, ‘Analyse’, involving use of appropriate technology tools, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning, enabling data analysts to not only analyse large sets of data coming in at high velocity in real time, but also reinforce the strategic changes into a feedback system. This enables the team to make changes at any node of the supply chain almost remotely and with nearly zero interruption to routine operations. The SSC provides the following two types of services to other group entities:

Provision of standardised data: SSC’s data analysts do not run any analytics but provide the standardised data to the requesting supply chain managers in other group entity. The usage, analysis or implementation of the data is at the discretion of the requesting entity; and

Provision of actionable insights: here SSC’s data analysts conduct in-depth analysis of the standardised data and provide real-time actionable insights to the requesting entity for an additional fee.

Since the type of service provided varies significantly, it is essential to price such inter-company services separately. For the purposes of realigning the company’s TP policies, companies may want to perform an in-depth value chain analysis to analyse activities that separate the routine tasks of data analysis from the strategic design of the analytical framework that may be developed by a handful of senior people.

The goal of the next step, ‘Learn’ is to continuously improve the data analytics process by changing the initial agenda for the data analytics and/or to apply the results from the ‘Analyse’ step to other aspects of the business. Additionally, it also allows the companies to perform tests against the measures of success, as defined in the first step of the framework and if required refine those measures of success for future operations.

It is important to recognise that the value of any digital transformation project is ultimately tied to how information is collected, stored and analysed to achieve the success factors of the company. Thinking of standardised data as a commodity is often helpful to break down the process of how this commodity can be produced and deployed for the ultimate benefit of the company.

TP strategy for digital transformation projects

Once the value chain analysis within the GOAL framework is completed, the value from digital projects can be allocated to each of the steps. A digital transformation project can drive benefits within an organisation by increasing revenues (by identifying new products and service offerings), saving costs (through generational greater operational efficiencies) or by simply enabling the company to maintain its current competitiveness.

Quantifying the ‘value’ of digital transformation, which is aligned with the value embedded in the amount of information it can generate, is the first step in a TP analysis. This value of information can be valued much as one would value any cash flow. The value of a cash flow is determined by the magnitude of cash one expects, the risk that it will not materialise as expected, and the time over which the cash will arrive.

A greater magnitude of money, generated at lower risk, and over a shorter time period all increase the cash flow’s value. The categories of magnitude, risk, and time are a framework within which one can identify the drivers that are relevant to a given use case. The elements identified above within each category are not intended to be definitive or exhaustive, although, as a practical matter, they are likely a good place to start and, in many cases, will prove sufficient for a TP analysis.

Since other group entities may be accessing the data or insights from the SSC, appropriate TP policies can also be put in place to compensate the SSC for its activities as suggested below:

Participation in cost sharing – Group stakeholders that can expect to realise future value from the database that is created as a part of a digital transformation initiative can decide to share the ex-ante costs of creating the database and get access to the database that houses all the information.

Cost plus fixed markup pricing – If the data being collected is routine it can be benchmarked using market comparables.

Two-part tariff – A hybrid pricing model can be adopted where some of the stakeholders can pay a ‘subscription fee’ to the database and then a user fee depending on the services that are performed using the data. This may be helpful if there is significant tax differential amongst the group entities.

Conclusion

Digital technologies are generally expected to significantly drive value within a MNE through a robust use of DDD tools and techniques. Recognising this value creation from data is therefore an essential element of designing a TP policy around the digital transformation initiative.

The application of the GOAL framework is aimed to provide tax managers a framework to document the key steps in creating value from using data and assigning the overall value from digital transformation projects to the relevant steps within the four GOAL steps, doing that within the DEMP approach stipulated by the 2017 OECD Guidelines.

Click here to read Deloitte's TP Change Management in Industries guide

Shanto Ghosh |

|

|---|---|

|

Principal Deloitte Tax LLP T: +1 617 437 3761 Shanto Ghosh is a principal in Deloitte’s TP practice in the US and is based in Boston. He has over 21 years of TP experience and leads Deloitte’s TP team in the Greater Boston area. Shanto has significant experience in advising clients from the life sciences, technology (including media and telecom), and industrial products sectors. He has been actively involved in assisting clients with their global TP policy and documentation and has implemented several large-scale global supply chain restructuring projects. He has significant experience in assisting clients on TP litigation and dispute resolution strategies and has been recognised in Euromoney/Legal Media’s ‘World’s Leading Transfer Pricing Advisers’ four times in a row. In addition to his consulting experience, Shanto is a visiting lecturer at Brandeis University and has been a teaching fellow at the Harvard Institute of International Development and a lecturer of Financial and Development Economics at the University of California, Berkeley. |

Priya Gopalakrishnan |

|

|---|---|

|

Managing director Deloitte Tax LLP T: +1 408 704 4301 E: prigopalakrishnan@deloitte.com Priya Gopalakrishnan is a managing director in Deloitte’s TP practice in the US and is based in Bay Area. She has over 16 years of TP experience and serves several large companies in the technology, media and telecommunication (TMT) industry. Priya has assisted clients in executing various complex projects involving intellectual property planning and migrations, TP planning advice around buy-in calculations owing to acquisitions, setting up of cost sharing arrangements, and implementing supply chain restructuring projects for large companies headquartered in the US. She has also been actively involved in assisting clients with their global TP policy and documentation and in implementing TP planning projects. She has advised clients from the semi-conductor, software, bio pharma and life science, health and nutrition, hospitality sectors and automobile sectors. Priya is a member of the California Institute of Certified Public Accountants and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. |