This article examines the intersection of the accelerating digital transformation in the oil and gas sector of the energy industry (industry) and the attendant transfer pricing (TP) considerations that multinational enterprises (MNEs) must navigate concurrently.

The introduction describes key industry forces that are driving this acute digital transformation. Next, prevalent digital technologies being developed and deployed in the industry are explored. As a consequence, the TP challenges and potential opportunities that these digital investments may create for MNEs are examined. Finally, future considerations that will need to be addressed as the industry grapples with these digital transformations are discussed.

Introduction

Industry stakeholder forces

A convergence of multiple stakeholders’ demands is driving the industry’s digital transformation, but two warrant specific mention and exemplify these forces.

First, the demographic mix of employee stakeholders continues to shift to an aged and contracted workforce population – 46% of employees lie in the 45+ age bracket and hundreds of thousands of jobs have been lost since the industry down-turn that started in 2014. This exodus of industry, institutional and operational expertise may create a knowledge-gap that must be bridged to sustain, or hopefully improve, health safety and environmental (HSE) metrics and increasingly stringent regulatory requirements. Digitalisation provides MNEs within the industry an opportunity to deploy technology and automation solutions to empower a broader, less experienced and dispersed work force with the expertise needed to deploy their skills in the most challenging and multifaceted industry environments.

Second, the transformative focus behind capital markets, governmental agencies and broader environmental groups on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues within the industry have empowered some stakeholders to demand change. Specifically, ESG initiatives around lowering carbon emissions, renewable energy sources, alternative energy and other ‘green’ initiatives have prompted the industry to evaluate new methods of extracting oil, gas, and other resources with less carbon footprint. Digital technologies (e.g. cleaner, more efficient drilling operations, remote monitoring of pipelines and rigs, cleaner burning fuels, more nimble supply-chain, etc.) offer the industry an important tool to both satisfy its core business objective of producing energy without sacrificing their ESG mission.

Financial and operational forces

Even before the global COVID-19 pandemic, the industry faced significant economic, financial, and operational challenges over the past five years. Supply shocks, break-down of long-standing geo-political stability, global demand declines, capital market preferences and general commodity price deterioration and volatility have made many participants in the industry reevaluate their cost structures, their capital budgets and their ultimate path/timeframe to navigate the pressures of energy transition. COVID-19 simply magnified these challenges. Digital technologies and transformation present an opportunity for the industry to increase operational efficiencies, stretch capital budgets, operate with less headcount and enhance productivity.

This is not simply a cost cutting exercise, but an organisational and change management challenge – a critical test for many large industry participants will be whether digital transformation eliminates institutional and operational silos that often exist between divisions within an MNE. It is not uncommon for trading, marketing, production, etc., in the same MNE, to have competing views of the facts, derived from distinct data sources.

Governance forces

Another aspect of the digital transformation will involve how processes, know-how, technology, etc. are actually owned and exploited. In the wake of recent initiatives from the OECD (e.g. BEPS, BEPS 2.0, pillar one, pillar two), there is considerable stakeholder interest in which jurisdiction is entitled to tax the earnings of an MNE. However, with dispersed workforces (magnified by COVID-19), enabling technologies, and digital workstreams, the application and understanding of tax and legal ownership of these transformative digital technologies becomes enigmatic. Industry participants, regardless of their risk tolerance or tax posture, will have to be very deliberate about where these digital technologies are owned and exploited within the MNE.

Digital technologies

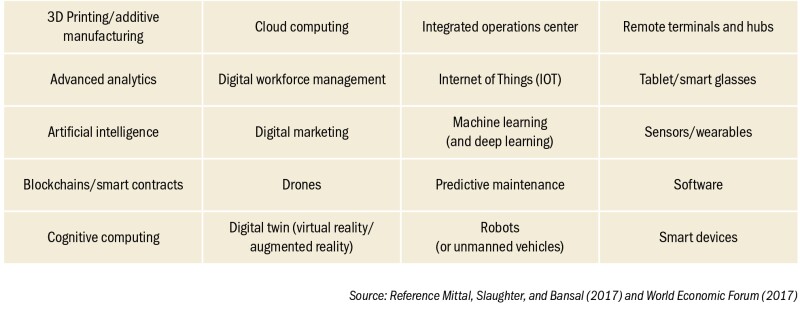

We now turn our attention to some of the technologies that are driving the digital transformation within the industry. Digital is a broad term encompassing technologies from data analytics to robotic automation. To consider the impact of the digital transformation on the industry, Figure 1 highlights some key digital technologies examples that are relevant to upstream, midstream, or the downstream segment of the industry value chain.

Figure 1: Digital technologies (examples)

Integration of digital technology may no longer be an aspirational goal, rather it has become part of the mandate for survival and future growth.

MNEs within the industry are embracing this change by implementing digital technologies that will drive value through both growth and operational efficiency. For example, as stated in a white paper by the World Economic Forum, advanced analytics and digital modeling technology will help to reduce the uncertainty in drilling, which will improve capital allocation and increase operational performance.

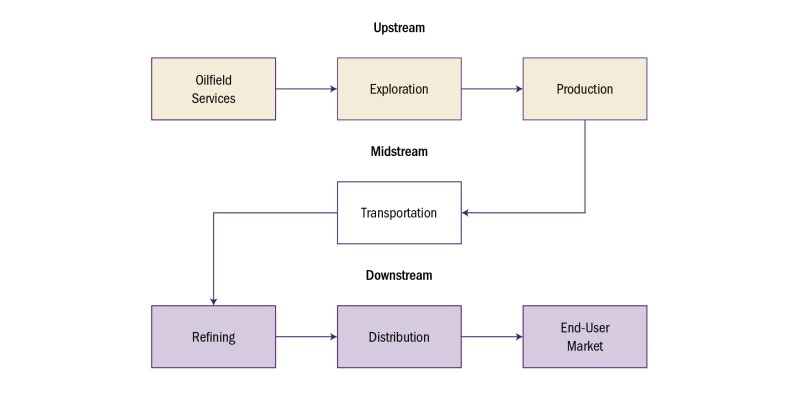

Furthermore, digital technologies provide a range of economic benefits, including reduced operational costs, greater operational efficiency, improved safety, reduction of system redundances, enhancing data-driven decisions, and greater connectivity across the industry value chain. Accordingly, the digital revolution is transforming both the value chain and economics of the industry. Historically, the industry was assumed to be linear with largely siloed processes that flow through upstream, midstream, and downstream stages, as depicted in Figure 2.

As shown in Figure 2, the traditional value chain depicts a process that begins with the oilfield services and ends with the end-user market (e.g. gasoline station), but in fact these processes may be seen as largely separate and distinct, as they relate to value creation.

Figure 2: Traditional industry value chain

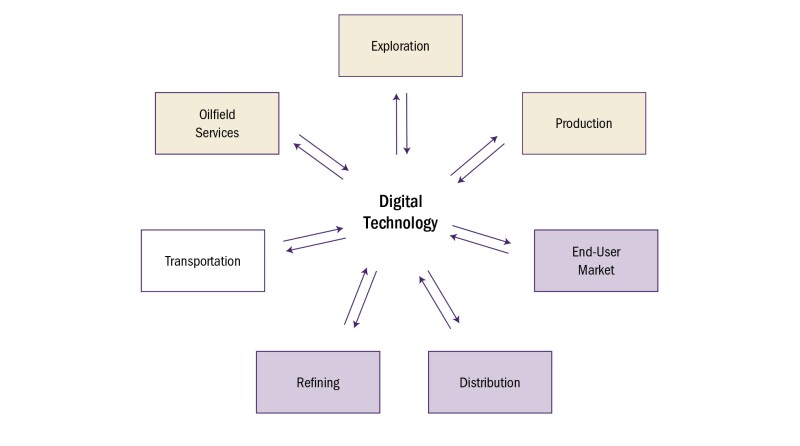

Digital technologies allow these separate chain segments to be connected and transform the value chain from a linear to a continuous process. As the industry catches up to digitalisation, the industry stands to benefit in coming years from increased connectivity and integration of processes in the value chain. As presented in Figure 3, digital technology is at the centre of the process and has the capacity to transform the historical chain into a new digital network.

Figure 3: Digital industry value network

This transformation from a value chain to de facto network will likely impact the underlying economics of how value is created by a firm in the industry. Traditionally, one of the key value drivers in the industry has been the ownership of physical (or tangible) assets. These assets may provide significant competitive advantages and create an opportunity to generate economic rents. Considerable value would be attributed to these physical assets in isolation, i.e. without the connectivity to other aspects of the enterprise. This is no longer the case in a digital world.

Digital technology allows physical assets (e.g. refineries, drilling rigs, storage, pipelines) and digital technology (e.g. software, machine learning, and cloud computing) to generate economic rents. Furthermore, the human element (e.g. know-how and internal processes) across the enterprise is enabled and augmented by the implementation of digital technologies.

Recognising that digital technology can transform the value creation process across the enterprise is important for both tax and TP professionals. With the above as background on how these digital technologies may transform the traditional value chain, we will highlight several key TP considerations associated with digital transformation.

TP considerations

As described above, the combined forces of structural change and transition to digitalisation have disrupted the value creation framework in the industry. Traditional reliance on human capital and legacy IP is amplified by specific digitalisation initiatives at virtually all levels of operations. Consequently, digitalisation has required the industry and advisors to take a fresh look at traditional TP concepts, such as ownership, management, use, and exploitation of intangibles and high-value services. As companies go through the process of digital transformation, they must also be aware of the increased complexity of this new value creation construct, as well as the changing global tax regime trying to capture this value.

Lifecycle of the digitalisation in the industry

A key characteristic of digitalisation that sets it apart from legacy value creation in the industry is the interconnectedness of the activities. Traditionally, many energy companies operated research and development (R&D) and engineering centres that resided at the top of the value creation pyramid, from which intellectual property (IP) was disseminated to field operations. By contrast, the core of digitalisation is interconnectedness that makes the IP value creation process dispersed throughout the MNE, makes ownership less centralised within the organisation and makes it more challenging to apply established TP approaches.

Assessing the impact of digital initiatives on key value drivers may have implications for the contractual arrangements between MNEs. Specifically, characterising the digital IP, determining which entities developed it, what is its value and whether remuneration is necessary must be critically examined.

Digital initiatives can often lead to relocation of functions, assets, and risks across legal entities, leading to a corresponding shift of value creation and the allocation of profits. In this dynamic environment, the arm’s-length principle becomes even more critical in ensuring that controlled transactions are appropriately designed, administered, and documented for TP purposes.

Determining the characterisation of and arm’s-length remuneration to digital IP

Digitalisation has the capacity to transform how businesses create value. As digitalisation transforms the industry, it is important to identify the value creation framework and determine what is digital IP versus a high-value service. For instance, a predictive algorithm that feeds diagnostics to determine maintenance needs, knowing where and how to direct crews, etc. could qualify as valuable digital IP. Conversely, field operations level data remotely gathered, processed, systematised into a knowledge platform that is an online problem resolution or diagnostic tool could be an example of technology-as-a-service (TaaS). How a particular type of transaction is structured and characterised at the outset may have far-reaching consequences as the transaction is adopted more widely in the coming years.

In either scenario, determination of value and TP analysis through traditional functions, assets, and risk analysis is complex. In a stylised example, an integrated oil and gas company might rely on sensors that detect abnormal temperature, data captured in an integrated operations center, a remote workforce monitoring the processes and remote engineers receiving alerts and incident details that enable ultimate delivery of services. In this continuum, the company would need to consider where the digital IP is in use or where value-add functions are performed and how much of the resulting profit should be left with each legal entity. The goal is to ensure alignment of value creation with the intercompany arrangements and resulting transfer prices across legal entities. It may be challenging to isolate value creation at each step and to accurately delineate functions, assets and risks between the legal entities involved in distinct, yet interconnected transactions.

To evaluate the impact of digitalisation on value creation, companies in the industry typically need to first isolate the outcome of value creation – whether it truly consists of digital IP or possibly value-added services.

In the case of digital IP, additional analysis of functions, assets, and risks should be conducted to determine whether the know-how or processes created qualify as intangibles per the US Section 482 regulations and the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines. Identification and application of the most reliable TP method(s) (best method in US practice) may involve complex considerations, as compared to historic transactions that took place as part of a more traditional value chain.

Analysing these ‘next generation’ controlled transactions may call for understanding of consideration of the reconstituted value chain and identification of the key factors that lead to the creation of economic value or specific intangible property. Among other things, this assessment may permit the TP analyst to determine whether value creation can be classified as a routine or non-routine activities, and accordingly whether a one-sided TP or a profit split method is more appropriate, based on the specific facts and circumstances.

Challenges of aligning the DEMPE functions around digital IP within the industry

Digital transformation presents significant tax regulatory challenges that may result in an erosion of the arm’s length standard, which had long been considered sacrosanct. BEPS 2.0, led by pillars one and two, has the potential to reset the central role of the arm’s length standard as it applies to certain specific types of transactions. A digital business model may have to address BEPS 2.0 as they continue to address challenges posed by OECD BEPS Action 8-10, which emphasised aligning TP outcomes with value creation.

The types of value creation that are likely to occur as a result of digital transformation are unique. The dynamic nature of activities and the rapid pace of adopting new or additional functions presents obvious challenges for a DEMPE analysis. Additionally, a new and improved paradigm can be disruptive to value creation within entities and hence their price or profit potential. Nevertheless, companies should consider developing a fundamental approach that is aligned with DEMPE-style analysis.

A thorough understanding of the value chain continuum and the potential impact of digitalisation on the MNE’s organisational structure, including functional departments, roles and responsibilities and reporting lines, is critical. This requires a central role for the tax function in companies that are experiencing digital transformation.

Furthermore, the dynamic and potentially complex changes to the value chain resulting from digitalisation may also increase the likelihood of tax controversy. In this rapidly evolving environment that presents new challenges, industry participants and their advisors will be required to perform the traditional tasks associated with TP compliance (factual and functional analysis, documentation, preparation of intercompany contracts, etc.). Performing TP analysis recognising the challenges and staying current with the documentation will be critical for the industry.

Future considerations

As evidenced above, a convergence of key stakeholder forces is driving digital transformation within the industry and poses critical challenges and potential opportunities for MNEs. Consistent with this speed of change is an urgency for tax and financial departments to understand i) how these digital technologies will change the MNEs value chain; ii) how potential shifts in digital IP ownership may be evolving; and iii) how this may impact the requisite legal entity profitability and arm’s-length related party transactions amongst the MNE.

Click here to read Deloitte's TP Change Management in Industries guide

Nick Gaudioso Jr |

|

|---|---|

|

Manager Deloitte US T: +1 713 982 3857 Nick is a manager for Deloitte Tax LLP in the US TP group. He has over seven years of TP consulting experience. Based in Houston, Nick provides services to clients across multiple industries including energy, software, technology, chemicals, real estate, private equity, and healthcare. In addition, Nick has experience with TP services including intellectual property planning and valuation, cost sharing arrangements, intercompany financing, global value chain alignment, headquarter or shared services cost allocations, US and global documentation, country-by-country reporting, TP audits, and advanced pricing agreement (APA) negotiations. Nick is a Certified Public Accountant and holds active licenses in Idaho and Texas. He holds an M.S. in Accounting and a B.B.A. in Accounting and Finance from Boise State University. Nick has published several articles on financial accounting, management accounting, and TP topics in trade and academic journals . |

Mayank Gautam |

|

|---|---|

|

Senior manager Deloitte US T: +1 713 982 2428 Mayank Gautam’s TP experience spans over 12 years providing specialist advice on diverse TP matters. Mayank focuses on the oil and gas industry and has deep expertise in the strategic areas of global planning, value-chain analysis, and restructuring involving design, implementation, and post-implementation review of corporate structures. His overall experience in TP covers a broad range including planning, global documentation, multijurisdictional cost sharing, and licensing of intangible property. He also has significant experience in TP controversies, dispute resolution and litigation matters, including assistance with competent authority negotiations and APAs. Mayank is a PhD economist from the University of Houston and holds a master’s degree in economics from Delhi School of Economics. He has authored articles on TP issues and is a regular speaker at the Tax Executive Institute (TEI). |

Randy G Price |

|

|---|---|

|

Managing director Deloitte US T: +1 713 982 4893 Randy G Price leads Deloitte’s TP practice in the Houston office and is one of Deloitte’s National Transfer Pricing Leaders for the oil and gas industry. Prior to joining Deloitte, Randy served as an international tax and TP leader for a Fortune 500 company. During his tenure in industry, he spent over a decade planning, implementing, and defending multiple TP transactions from design, execution and implementation through IRS appeals and Tax Court. In addition, he has participated directly in the defense and ultimate quashing of an IRS summons enforcement action in United States District Court related to a TP information request. Randy’s TP practice and experiences span the entire spectrum of the oil and gas value chain. He works with many of the world’s largest oil and gas companies in planning and coordinating their global TP strategy and documentation. Randy holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the McCombs School of Business, University of Texas at Austin as well as a global energy MBA degree from the University of Houston. He is also a CFA Charterholder and registered CPA in the State of Texas. |