Over the past few years there has been an upsurge of private equity (PE) activity in the Asia-Pacific (AP) region, due to the size and increasing affluence of the Asian market. However, the AP region is diverse in its tax regime and tax complexity, which can pose unique tax challenges and give rise to various diligence and structuring concerns in a transaction.

In this article, we explore what companies looking to buy a PE-owned business in AP, or PE fund managers looking for deals in AP, may need to consider.

The PE landscape in AP

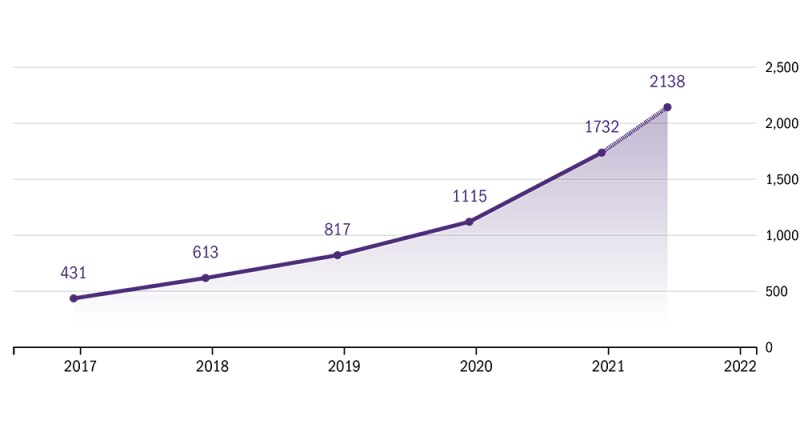

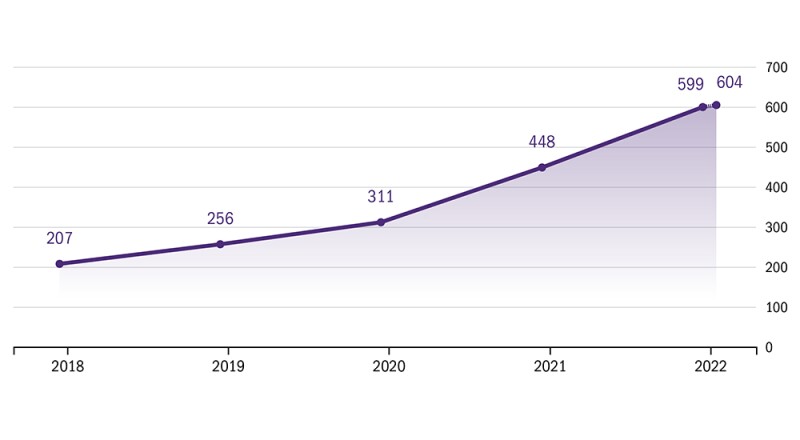

The PE market in Asia has been growing rapidly. AP-based PE assets under management reached record levels of $2.1 trillion as of June 2021 while dry powder was $604 billion as of January 2022.

There is also strong demand for deals as evidenced by 809 AP buyouts – an all-time high – completed in 2021. We expect this momentum to continue in 2022 (see Figure 1).

The key trends amid robust deal activity in the AP region include:

Monetary and fiscal stimulus continues to drive prices up: Auctions are extremely competitive and PE firms have to bid high to win. To justify top-end valuations, PE firms are eager to explore post deal value creation opportunities such as bolt-ons and business optimisation.

Digital transformation remains a key business priority and deal flow driver: Digital consumer behaviours and business dependency on networks continue to create new demand. The impact of digital transformation is a key consideration when PE firms make investment decisions.

More dedicated funds in Asia: Dedicated Asia funds will continue to drive increasing deal activity in the AP region.

Newly introduced special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) listing frameworks will offer practical exit options: Although SPACs are at an early stage in Hong Kong SAR and Singapore, we expect increased use of SPACs as an alternative to traditional initial public offerings as a result of strong investor demand, rising capital and liquidity in the market and the recent rise in market volatility.

Figure 1

AP based private equity assets under management (US$ bn)

AP based private equity dry powder (US$ bn)

Tax diligence issues when buying a PE-owned company

The common tax diligence issues in AP that you may consider when buying a target from a PE fund include:

Understanding the target legal structure: Consider the applicability of the relevant treaties in relation to profit repatriations within the target group, especially around inter-company flows in the form of dividends and interest, including the ‘substance’ of any intermediate holding companies. Where there is insufficient substance the key issue is whether the relevant tax authority can challenge the treaty rates being applied on cross-border payments from a ‘treaty shopping’ perspective.

Complex financing structures: Tax diligence for capital-intensive or leveraged businesses (which is a common trait of PE investments) is often focused on issues such as deductibility of interest payments and withholding tax for interest payments made offshore. Financing structures typically used for PE investments need to be carefully analysed from a transfer pricing (TP), thin-capitalisation and anti-hybrid mismatch perspective. Furthermore, the unwinding of mezzanine financial instruments such as redeemable preference shares often needs to be done via completion mechanisms that must be included in transaction agreements and relevant purchase price adjustments. This is typically complex and needs to be addressed from a legal, accounting and tax perspective.

Capital v. revenue: This is always an important issue for both buyers and sellers of businesses. For example, Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, Malaysia and New Zealand do not tax capital gains. However, the question of whether a gain should be capital or revenue in nature is often contentious, and challenges from tax authorities may be protracted. If the target company has disposed of assets in the past, it will be difficult to get indemnities from a PE seller as the PE fund will need to distribute the proceeds fairly quickly to maximise returns. In view of the uncertainty, apart from other mechanisms such as escrow account, tax insurance is gradually gaining popularity as an effective way to limit the downside risks and enable the deal to move forward. However, not all risks are insurable or cost-effective to insure; hence proper research and an external professional opinion is usually needed.

Indirect share transfers: In China (PRC), the indirect transfer of PRC shares may give rise to historical tax risks, if these are not properly reported to the PRC tax authorities. This can also become a transaction risk as the buyer may be held responsible for the taxes in a non-reporting scenario. For example, in Vietnam the capital gains tax burden in an indirect share transfer scenario shifts from the seller to the Vietnam target subsidiary if such tax is not paid by the seller.

Relevant to all AP jurisdictions is the TP risk on related party transactions: Understanding the basis for asserting that allrelated party transactions (particularly intra-group trading and related party financing transactions) are carried out on an arm’s-length basis is critical. It should be noted that given tight deal timelines this analysis generally only provides a directional view of the intra-group TP risks which the buyer should consider at the transaction stage, and any material risks or gaps should be addressed post-completion with a more thorough review or benchmarking exercise. A number of AP jurisdictions have started imposing mandatory TP documentation requirements. Hence tax diligence can help to identify if such TP compliance requirements have been adhered to, as there are usually penalties for not preparing TP documentation on a timely basis. If a target group has commissioned TP benchmarking studies, at least for the material intra-group transactions, it helps to provide comfort that TP risks have been duly considered and addressed.

A number of PE transactions in AP utilise warranty and indemnity insurance: A common theme across AP is that insurers are not covering tax risks that are raised in diligence reports. Buyers need to realise that they may not be covered for such historical exposures and may need to seek separate tax insurance for material tax issues.

Management incentive plans (MIPs): These have always been important in PE deals. However, we are seeing an increased urgency (particularly on ‘auction deals’) to have MIPs fully in place before final bids are lodged. For companies acquiring PE-owned companies, it is important to not only understand what is in place, but also what plan the purchaser is going to implement, as the termination or swap of existing MIPs can trigger a tax liability for the relevant executives without cash being made available to them and can be a key negotiating point for the purchaser.

Finally, government stimulus has been unprecedented due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, a critical diligence issue in Australia is ensuring that companies that have taken advantage of such stimulus (such as the JobKeeper scheme) have complied with the relevant conditions. The Australian Tax Office is vigorously reviewing companies’ compliance with accessing this stimulus. This risk may be replicated across the AP jurisdictions as governments in AP shift their focus from providing temporary economic support to businesses to ensuring that there have been no excess payments and companies are not taking undue advantage of the schemes.

Tax structuring issues for a PE fund manager

We have so far discussed some tax diligence issues that may be relevant for a PE-owned target. Putting on a different lens, we next consider some of the structuring issues related to maximising the returns from the investment, from the perspective of a tax director working for a PE fund.

Historically, PE investments have been leveraged based on local jurisdiction thin-capitalisation rules and related party debt pricing. This often, within the rules, offers a certain tax shield. But the landscape has somewhat changed with the introduction of the OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) rules.

Generally, the OECD BEPS project provides that profits should be taxed where the real economic activities generating profits are performed and where value is created. In addressing the residual tax challenges of the digital economy, new rules are being developed that essentially allow market jurisdictions to tax a share of the multinational enterprise’s profits and allow countries to impose a top-up tax in the parent jurisdiction under a common framework.

PE funds may be affected by BEPS in the following ways:

Limiting interest deduction (BEPS Action 4): This may have an impact on group financing structures adopted by PE funds should local jurisdictions amend their domestic tax law to align with Action 4, e.g. limiting interest deduction to 30% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA), which may result in double taxation within the group. PE funds may need to re-look at the target’s financing arrangements and consider restructuring or alternatives, such as cash pooling.

Principal purpose test (PPT) (BEPS Action 6): The PPT seeks to deny tax treaty benefits in cases where one of the principal purposes of the arrangement or transaction is to secure a benefit in a manner that is contrary to the object and purpose of the tax treaty. With the PPT in place, it has further reinforced the expectation that commercial substance is required before treaty benefits can be available especially in relation to dividend, interest and royalty flows.

On-shoring of fund jurisdictions: With the focus on substance and the scrutiny on tax haven jurisdictions, we have seen an on-shoring of funds to align the fund platform or pooling jurisdiction to where the fund manager’s employees are based. It is common, where sufficient substance and activities are being undertaken in the relevant fund jurisdiction, to access local country tax exemption schemes to further mitigate the PE fund’s tax exposures. These include the resident fund and enhanced-tier fund exemption schemes in Singapore and Hong Kong SAR’s unified fund exemption scheme. Such on-shoring of fund jurisdictions can also facilitate easier access to tax treaty benefits. However, although these schemes provide tax certainty, they may involve higher administrative costs and other tax costs in the fund jurisdiction such as stamp duties. Value-added taxes also need to be factored in.

BEPS 2.0

The world is undergoing a global tax reform, including the implementation of a global minimum tax rate of 15%, termed ‘Pillar Two’ under the BEPS 2.0 initiative. Based on the Pillar Two model rules issued on December 20 2021, groups with annual consolidated group revenue of at least €750 million in at least two of the four immediately preceding fiscal years will be in scope for the minimum tax, which is to be collected in the parent jurisdiction, if the effective tax rate (ETR) in the subsidiary jurisdiction is below the 15% threshold. So far, more than 135 countries have signed up to the inclusive framework that developed the global minimum tax rules.

|

|

“Over the past few years there has been an upsurge of private equity activity in the Asia-Pacific region, due to the size and increasing affluence of the Asian market.” |

|

|

Certain entities, including investment funds and real estate investment vehicles that are ultimate parent companies, will be excluded from the ambit of Pillar Two. This requires the fund or its management to be subject to a certain regulatory regime, among other conditions. Even if investment funds may not be subject to the global minimum tax rate of 15%, the sub-groups, such as the portfolio entities held below the PE funds, may themselves be subject to the rules to the extent that their group revenue exceeds the threshold of €750 million.

The global minimum tax regime may increase the ETR of the PE firm’s portfolio entities, which will affect the after-tax returns of the PE fund. It remains to be seen how AP jurisdictions are adopting these new rules and the amendments that may be made to their domestic tax legislation to be consistent with the rules, considering the need to protect their own tax base while continuing to remain attractive to investments. There may also be preferential tax regimes designed to comply with the Pillar Two rules, especially in higher tax jurisdictions such as Australia, or where the group revenue of the portfolio entity does not exceed the €750 million threshold.

Looking forward

To conclude, we expect the AP region to continue to be a key area of growth and M&A activity. However, there are increasing tax risks on the horizon and local tax authorities are expected to be more focused on tax audits and revenue raising measures. This, coupled with unprecedented changes in international tax rules, means that tax directors should remain aware and stay on top of these developments, to adapt to any tax headwinds that arise.

Click here to read all the chapters from ITR's M&A Special Focus

Amrish Shah |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Deloitte India T: +91 22 6185 4310 Amrish Shah heads the M&A tax practice of Deloitte in India and Asia Pacific. He has more than 29 years of post-qualification experience, and has previously worked with Indian boutique tax firms and the Big Four firms. Amrish has advised large multinational and Indian companies on acquisition/divestment tax and regulatory structuring as well as direct tax due diligence assignments. He has also assisted them in corporate reorganisation including mergers/demergers and joint ventures, and has advised PE clients on acquisition/divestments. He was part of the CII Tax Committee in 2014. Amrish regularly contributes thoughts on broadcast and print media. |

Daniel Ho |

|

|---|---|

|

Tax partner Deloitte Singapore T: +65 6216 3189 Daniel Ho is an M&A tax partner with more than 22 years of tax experience in companies in industries such as real estate, fund management, technology, manufacturing, consumer products, shipping/energy and resources. Daniel has extensive experience in Singapore and international tax consultancy and planning in the area of IPOs, corporate restructuring, M&A, cross-border payments, supply-chain planning and permanent establishment issues. He has been involved in numerous tax structuring and due diligence assignments for corporates and private equity funds. Daniel has been named in International Tax Review’s Tax Controversy Leaders Guide in 2016, 2017, 2018, 2020 and 2021 and Expert Guides’ 2018 and 2020 World’s Leading Tax Advisors. |

Brett Todd |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Deloitte Australia T: +61 3 9671 7989 Brett Todd is an M&A tax partner at Deloitte. He has over 24 years of experience providing specialist taxation advice on M&A, PE, cross-border structuring and domestic tax structuring. Brett specialises in PE investments and works with some of largest PE funds in AP where he has worked on some of the biggest transactions in Australia. As part of his time at Deloitte, Brett has held various senior leadership positions. These include national managing partner: tax (including national executive member and global tax executive member), national leader: cross-border tax (M&A, international tax and TP), national leader: M&A, Australian representative: Deloitte global advisory council and Victorian leader: corporate and international tax. |

Dwight Hooper |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Deloitte China – Hong Kong SAR T: +852 6293 7650 Dwight Hooper is a partner at Deloitte China – Hong Kong SAR. Dwight has over 25 years of experience working on PE transactions across North America and AP. He has undertaken overseas assignments in New York and Hong Kong SAR and spent the majority of his career focused on PE clients. Dwight leads Deloitte’s PE business for Asia Pacific. For the past 10 years, Dwight has been based in Hong Kong SAR executing transactions for global private equity across almost all AP geographies. |